The “Save the Gold of Switzerland” Initiative. Why the Swiss Central Bank and Government Campaigned Against It

With the abolition of the gold standard in 1971 by then President Nixon, dollar denominated reserves in the coffers of the world were no longer directly convertible into gold. The agreement of the 1944 established so-called “Bretton Woods System” was therefore broken, opening the way for free floating fiat currencies – free to be printed at will without any backing of gold or a country’s economic output. The fiat system remains in place as of this day.

The Bretton Woods System that (re)-introduced the gold standard – an official convertibility rate of US$ 35 per troy ounce (about 32 grams) – was named after the town in New Hampshire, where 44 nations met in 1944 to develop a new international monetary system – and incidentally, where at the same time the IMF and the World Bank were founded. Switzerland was not part of the party, as it joined the IMF / WB system only in May 1992. However, the IMF and the World Bank moved on from a currency regulator and reconstruction (Europe) organization to today’s largest international financial institutions with powers to make or break a country.

In 2011 the world’s total gold holdings, according to official statistics were 171,300 tons, of which almost half is in jewelry and less than 20% in Central Banks. Extrapolating from an annual gold production of about 2,400 tons today’s (2014) total (official) gold holdings should be close to 180,000 tons.

The Swiss always had a special affair with gold. Since WWI the Swiss currency was coveted as a reserve currency, similar to gold and the US dollar. After the (re)-establishment of the gold standard in 1944 Switzerland accumulated gold that reached a level of close to 5,000 tons by 1970, accounting for more than half the Swiss foreign exchange reserves and covering circulating paper money with up to 120% of gold.

At the end of the 1990’s, the SNB had 2,590 tons of gold to comply with the obligation to still back a portion of the paper money in circulation with gold. At that time the gold reserves constituted about 43% of total reserves. That proportion shrunk to 18% by 2009 and to 7 % in 2014.

In 1999, Switzerland became a signatory of the so-called Washington Agreement on Gold Sales (WAGS), joining most of the OECD ‘hard currency’ countries. The WAGS basically meant that gold was “no longer needed for monetary policy”, thereby setting gold free for sale by central banks at market prices – and for huge profits. Accordingly, Swiss monetary policy followed the neoliberal dictate of fiat money and instant profit taking.

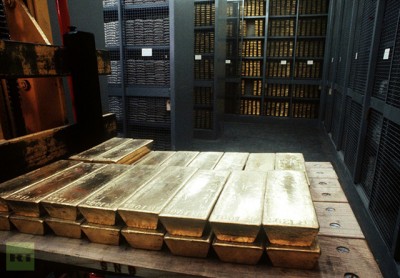

Between 1993 and 2014 Switzerland sold about 1,600 tons of gold, way more than any country, more than half of it during the 2000 – 2004 period, when gold prices were at the lowest between US$ 300 and US$ 500 / oz. By September 2014, SNB gold reserves were (officially) at 1,040 tons (7 %). Yet, Switzerland is still the 7th largest gold holder in the world, after the US with 8,130 tons (72% of reserves), Germany 3,400 tons (67%), Italy 2,450 tons (66%), France 2,435 tons (65%), Russia 1,170 tons (10%) and China 1,055 tons (1%). The IMF is reported as holding 2,800 tons. These are official figures. They may hide underreporting, especially for Russia and China – and possibly also for Switzerland.

In per capita terms Switzerland is with 128 grams (not counting jewelry and other privately owned gold) by far the largest gold holder in the world, followed by Germany (42 grams), Italy (40), France (38) and the United States (26). This actually follows the Swiss gold tradition, a tradition of a stable currency enhanced by the Swiss neutrality throughout WWII – and to some extent until today. The sense of owning Swiss francs in times of crisis is growing.

The onset of the 2008 financial crisis has again meant huge sums of foreign currencies flowing into Switzerland and converted into Swiss francs (CHF). This has further strengthening the franc, making it according to the SNB and the Federal Government, a central-right coalition, an over-valued currency and Swiss exports uncompetitive. Indeed, the value of the CHF has been steadily rising. At the end of 2007 it was pegged at CHF 1.60 per Euro, increasing to CHF 1.25 at the end of 2010, peaking in august 2011 at 1.09, fast approaching a 1 : 1 ratio.

Between 1970 and 2008 the CHF appreciated by close to 330% against US$ and about 60% vs the Euro. The Euro exists as virtual currency since 1 Jan 1999, and sine 2002 in notes and coins. Before the creation of the Euro, the CHF was closely linked to a basket of major EU currencies, and followed the so-called ‘snake’ – the fluctuation of the basket’s average, the strongest component of which was the Deutsche Mark.

Swiss external trading is to 80% with the European Union, the bulk of it with Germany. Switzerland without natural resources to speak of is a country of exports, mainly manufacturing of high precision equipment and services, notably banking and tourism. Competitiveness with the euro is therefore important.

On 6 September 2011, the constitutionally autonomous SNB, driven by the Swiss industrial lobbies and supported by the Federal Government, took the unusual step of force-devaluing the franc by about 10%, fixing a Swiss franc / Euro floor of CHF 1.20 per Euro.

In a Press Release of 6 Sept 2011, the SNB announced –

The Swiss National Bank (SNB) is therefore aiming for a substantial and sustained weakening of the Swiss franc. With immediate effect, it will no longer tolerate a EUR/CHF exchange rate below the minimum rate of CHF 1.20. The SNB will enforce this minimum rate with the utmost determination and is prepared to buy foreign currency in unlimited quantities.

To maintain this exchange rate means the SNB needs utmost flexibility to (i) print money according to needs which has become common place in our western neoliberal monetary system, and (ii) to ‘play’ with its reserves, including with gold – buying and selling, according to needs, also called multi-currency swapping.

The SNB’s balance sheet is one of the most lucrative in the world, and has become even more so after the forced CHF 1.20 / Euro parity. Total SNB assets in 1997 were CHF 70 billion, increasing to CHF 270 billion in 2011, the time of the CHF-Euro parity decision – and doubling three years later, in 2014 to CHF 550 billion. One could conclude that the devaluation was highly profitable.

The question that begs to be asked is who are the main beneficiaries of a force-devaluation in a country that has already one of the highest and most expensive living standard in the world? According to Eurostat, the European Union’s official bureau of statistics, in a basket of living costs of the 28 EU members plus Switzerland and Norway, where the average living cost is 100%, Switzerland’s cost of living is by far the highest with 164%, followed by Norway (156) and Denmark (154) and way down by Germany (107) and France (108).

Switzerland is a country of monopolies. Not being a member of the EU enhances the monopolies and thereby the high cost of living – which benefits the rich and creates a growing gap between them and the poorer segments of the population. A force-devaluation of the currency enhances the status quo, i.e. the holders of the monopolies have to do little or nothing to adapt their prices (and profits) to the high value of the currency – and to the competition outside of Switzerland. They survive well and the Swiss economy keeps growing. Unemployment has been kept low at 3.1 % (November 2014), with a slight tendency to increase – and with a so far unspoken uncertainty of the future in a surrounding EU economic system on decline, on which the Swiss economy highly depends.

The common Swiss, the base of the right wing Swiss People’s Party, is wary. They sense that things have changed, that the stability of Europe, the world, is not what it used to be a decade ago. They see wars all over the globe and hear propaganda and threats of a WWIII or a Cold War II. They look in fear to the East, where Russia is an alleged new threat, after the nasty Soviet Union was defeated 25 years ago. They see key currencies, like the euro and the dollar, waning and with the Swiss franc pegged to the Euro; its traditional high value of stability also risks declining. When the CHF was backed by gold, there was no risk for the national currency.

The “Save the Swiss Gold” initiative was launched in 2011 by the Swiss People’s Party. One of the architects and key drivers of the initiative, Mr. Stamm, said the measure was needed because the SNB’S monetary policy now tied Switzerland to the weakened euro and will further weaken the Swiss franc.

The referendum required that

– The SNB must hold at least 20% of its total assets in gold;

– The SNB does not have the right to sell its gold; and

– All the gold of the SNB must be stored physically in Switzerland.

The first two points would severely curtail the SNB’s range of activity to maintain the CHF 1.20 parity to the euro. To comply with the requirements, increasing the current level of 7% of reserves to 20% could be achieved over five years. It would mean the SNB would have to buy every year close to 14% of the current world gold production, i.e. a 5-year total of 1,700 tons at a price of CHF 67 billion (US$ 70 billion), at an assumed average price of CHF 1,250 / oz. (current gold price is CHF 1,165 and falling). This would have an impact on the precious metal’s value, as well as on maintaining the ‘sacred’ 1.20 parity.

A spokesman for the Swiss Economic Institute said,

The SNB would not be prohibited from defending the level [of CHF 1.20 / Euro], but it would need to keep its gold ratio at 20% of holdings, so for every euro it will buy in the market to defend the floor, it would need to add more gold to its reserves – permanently. The SNB’s ability to defend its floor would be seriously hampered. The accumulation of unsellable gold would impose an enormous restriction on the conduct of the SNB’s monetary policy.

As with many things in Switzerland, gold is shrouded in secrecy. Nobody knows exactly where it is stored, how much of it is in Switzerland. When the Finance Minister was asked recently by a parliamentarian about the whereabouts of the Swiss gold reserves, he answered he didn’t know and he didn’t want to know. However, since gold is of high importance to the Swiss, they have always considered SNB’s gold reserves as the property of the Swiss people. Many of them, on both sides of the aisle, were upset when in 2000 after a constitutional change prompted by the signing of the Washington Agreement on Gold Sales, the SNB started selling its gold.

The initiative was basically ignored by the ‘market’ and most of Switzerland until October, when polls indicated a 44% ‘yes’ vote – or a too-close-to-call prediction. These were dangerous signs for the SNB and the Swiss Federal Council – that it might be accepted, which means strong restrictions in SNB’s maneuvering capacity – trading with its reserves.

At the last hour the SNB and the Federal Government issued warnings that accepting the referendum would mean a severe hindrance in SNB’s freedom of action to maintain the CHF-Euro parity – which is sacrosanct to the Swiss business community.

They finally succeeded. On 30 November 2014, the referendum was defeated by 78% of popular votes.

However, this is likely not the end of the gold story. The referendum has stirred a lot of attention to the importance of gold in Switzerland and around the world. Though the SNB’s liberty to maneuver its forex reserves freely will remain intact, people and politicians will put more pressure on transparency. Worldwide, lovers of the gold standard will be awakened and encouraged, when instead the attention should be on a new monetary system, based on a country’s real output, social and physical. By all accounts, gold is not eatable. What is its real value in a crisis, other than feeding an illusion?

Peter Koenig is an economist and geopolitical analyst. He is also a former World Bank staff and worked extensively around the world in the fields of environment and water resources. He writes regularly for Global Research, ICH, RT, the Voice of Russia, now Ria Novosti, The Vineyard of The Saker Blog, and other internet sites. He is the author of Implosion – An Economic Thriller about War, Environmental Destruction and Corporate Greed – fiction based on facts and on 30 years of World Bank experience around the globe.