The State-Name of Macedonia. Historical Analysis, Political Implications

The “Macedonian Question” is today actual for several reasons of whom two are of the fundamental importance:

1. The Albanian secession in the FYROM; and

2. The Greek dispute with the FYROM authorities over several issues.[1]

For the matter of illustration, for instance, Greece is so far blocking Macedonia’s joining NATO and the EU because of an on-going dispute between the FYROM and Greece. The main disputable issue is the title of “Macedonia” used in the country’s Constitution in the form of the official state-name as the Republic of Macedonia.[2] When the ex-Yugoslav Socialist Republic of Macedonia voted for independence on September 8th, 1991[3] as the Republic of Macedonia that was confirmed as the official constitutional name in November 1991[4], Greece became with a great reason immediately reluctant of recognising the country under such official name in addition to some other significant disputable issues in regard to the independence of FYROM.

In essence, according to the Greek administration, the use of this name is bringing direct cultural, national and territorial threat to Greece and the Greek people. The Greeks feel that by using such name, the FYROM imposes open territorial claim on the territory of the North Greece that is also called (the Aegean) Macedonia. To make things clear, Greece claims and with a right reason, to have an exclusive copyright to the use of the name of Macedonia as the history and culture of ancient Macedonia were and are integral parts of the Greek national history and civilization and nothing to do with the present-day “Macedonians” who are the artificial creation by the Titoist regime of the Socialist Yugoslavia after the WWII.[5]

The FYROM (the Republic of Macedonia)

A Basic Historical Background

A present-day territory of FYROM was formerly part of the Byzantine, Bulgarian and Serbian Empires until 1371/1395 when it became included into the Ottoman Sultanate followed by the process of Islamization. The Christian population of the land was constantly migrating from Macedonia under the Ottoman rule especially after the Austrian-Ottoman wars and uprisings against the Ottoman rule. After the 1878 Berlin Congress, Bulgaria started to work on annexation of all historical-geographic Macedonia and for that reason it was established in 1893 openly pro-Bulgarian Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (the IMRO).

After the Second Balkan War in 1913 Macedonian territory became partitioned between Greece, Serbia and Bulgaria. During the WWI, Macedonia was a scene of a heavy battles between the forces of the Central Powers and the Entente (the Salonika Front or the Macedonian Front). After the WWI, according to the Treaty of Neuilly, the territorial division of historical-geographical Macedonia between Serbia (now the Yugoslav state), Greece and Bulgaria was confirmed followed in the next years by a large population movement which transformed the ethnic and confessional composition of Macedonia’s population primarily due to the population exchange between Greece and Turkey after the Greco-Turkish War of 1919−1922. In the interwar period, despite continued activism by the IMRO terrorists from Bulgaria, the aim to annex the Yugoslav (Vardar) Macedonia became unfulfilled. After WWII, the Vardar Macedonia became transformed into one of six Yugoslav socialist republics (the Socialist Republic of Macedonia) followed by the official recognition of the Macedonian nation, language and alphabet by the Yugoslav communist authorities – a decision which alienated Bulgaria and Greece from Yugoslavia.[6]

The proclamation of state independence of the Yugoslav portion of Macedonia under the official name the Republic of Macedonia immediately created an extremely tense relationship with the neighbouring Greece as Macedonia developed rival claims for ethnicity and statehood followed by the appropriation of the ancient Macedonian history and culture. This Greco-Macedonian rivalry became firstly epitomized in a dispute on Macedonia’s official state-name for the very reason that Greece objected to the use of the term Macedonia in any combination of the name of the state of its northern neighbour.

An Origin of the Dispute

The dispute between Greece and the FYROM regarding the Macedonian official state-name came on agenda when ex-Yugoslav Socialist Republic of Macedonia adopted its new Constitution in November 1991 in which the country official name was declared as the Republic of Macedonia. As a matter of political fight against the FYROM Government, Greece blocked the European Union (the EU) to recognize Macedonia’s independence[7] and on December 4th, 1991, the Greek Government officially declared its good will to recognize the independence of ex-Yugoslav Socialist Republic of Macedonia but only if it would:

- Made a clear constitutional guarantee of having no claims to the Greek territory.

- Stop a hostile propaganda against Greece.

- Exclude the term “Macedonia” and its derivatives from a new official name of the state.

The first of these three conditions was a Greek reaction to the disputable Article 49 in Macedonia’s new Constitution which declared that the Republic of Macedonia cares for the status and rights of those persons belonging to the Macedonian people in all neighbouring countries as well as the Macedonian expatriates, assisting in their cultural development, and promoting links with them.[8] This article was interpreted by Greece as an indirect reference to the (unrecognized) Macedonian minority (i.e. “Slavophile Greeks”) in the North Greece (the Aegean Macedonia) and it was perceived as a threat to the territorial sovereignty and integrity of Greece. The EU concerning this matter supported Greece and stated in the same month that it would only recognize a new Macedonian state if it guaranteed to have no territorial claims against any neighbouring EU member state[9] and not to engage in any act against such state, including and the use of a state-name that potentially can imply the territorial claims.

Basically, only under the pressure by Brussels, the Parliament (Sobranie) in Skopje amended Macedonia’s Constitution in January 1992 and as the results, the formal constitutional guarantees were provided that the country would not interfere in the internal affairs of other states and would respect the inviolability of the international borders of any state. Macedonia’s authorities fulfilled only the minor EU requirements, hopping to be soon recognized by the same organization, but two crucial problem-issues (the state-name of Macedonia and the Article 49 in the Constitution) which caused the fundamental Greek dissatisfaction, still remained unchanged. Therefore, the EU sided with Greece and decided in June 1992 not to recognize the republic if it uses the term Macedonia in its official state title.[10]

However, at the first glance, it may seem that the EU supported the Greek policy in 1991 toward the Macedonian Question as it aligned itself with Greece as a member state of the bloc, but in fact, it was not the case. Greece’s position and arguments have been publicly rejected and even ridiculed by the officials from several EU member states, but three crucial real politik reasons made the EU to officially side in 1992 with Greece in her dispute with the FYROM:

- In an exchange for the EU support on the Macedonian Question, Greece promised to ratify the Maastricht Treaty (signed in February 1993), to participate in sanctions against Serbia (its traditional ally), and to ratify the EU financial protocol with Turkey.

- By taking the same position as Greece, the EU demonstrated its own internal political cohesion and unity, trying at the same time to thwart the use of Greek veto right in order to protect its own national interest within the EU.

- A last factor that contributed to the EU support for the Greek case was a fear that the Greek Government might fall if the Republic of Macedonia would be recognized under that name.[11]

Alternative Official Names for Macedonia

A variety of alternative names for ex-Yugoslav Socialist Republic of Macedonia were proposed after 1991 in order to solve the problem and normalize relations with Greece – a most important Macedonia’s neighbour and economic partner. It was quite clear that Greece herself would not accept any kind of state-name that includes a term “Macedonia” and therefore a variety of solutions without a term of “Macedonia” were suggested by Athens, ranging from Dardania and Paeonia (used in antiquity to name regions to the north of the ancient Macedonia) to the names of the South Slavia, the Vardar Republic[12], the Central Balkan Republic and the Republic of Skopje (named after Macedonia’s capital). All other name suggestions which used the designation Macedonia, mainly proposed by the Macedonian side, were in no way acceptable to Greece from political, historical and moral reasons.

What Greece could accept as a kind of temporal solution was the state-name of the country with the designation Macedonia but only to make clear difference between Macedonia as a former republic of Yugoslavia and Macedonia that is a region in (the North) Greece. These solutions included names, for instance, the North Macedonia, a New Macedonia or the Slavic Republic of Macedonia.[13] Greece even suggested that a new state of Macedonia could adopt two names: 1. One official for the external use, without mentioning designation Macedonia, and 2. One unofficial for internal use, which could include designation Macedonia. However, all these Greek solutions were rejected by the Macedonian authorities who insisted on the recognition of Macedonia’s independence exactly under the constitutional name of the Republic of Macedonia.[14]

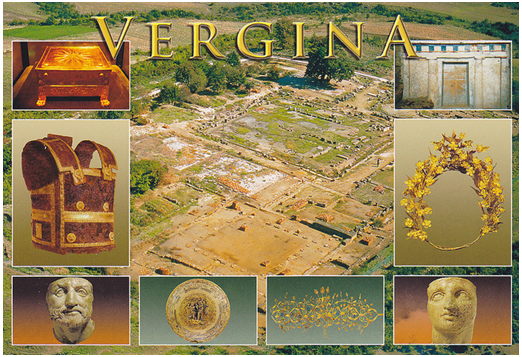

Ancient Vergina in Greece

The FYROM and the “Sun of Vergina”

The ex-Yugoslav Socialist Republic of Macedonia was gaining the international recognition step by step, although not in majority cases under its constitutional name as the Republic of Macedonia. By early 1993 the new state was able to become a member of the International Monetary Fund (the IMF) under the name the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (the FYROM)[15] and by April 1993 the United Nations (the UN) also admitted Macedonia under such provisional name as a temporal compromise between the Macedonian and the Greek authorities. It was agreed that a permanent state-name of Macedonia that is going to be used in the foreign affairs had to be decided later through a process of mediation by the UN. However, the FYROM was not allowed to fly its original state flag (from 1991) at the UN headquarters as the official state emblem as Greece strongly opposed such idea.

The real reason for this Greek decision was basically of the essential nature of the political conflict with the authorities in Skopje as the flag was composed by the yellow-coloured sixteen-ray sun of star from Vergina on the red-coloured background. The background colour was not a problematic issue, but the yellow “Sun of Vergina” on the flag, however, created the fundamental dispute between two states together with the issue of the official state-name of Macedonia. The Greek Government strongly opposed the Macedonian authorities to use the “Sun of Vergina” as a state emblem at least for two good reasons as:

- It was an insignia of the ancient Macedonians of the Macedonian Empire.

- It was found between two world wars in Vergina that is an ancient town on the territory of the present-day Greece but not of the FYROM.

The Greek authorities is understanding the “Sun of Vergina” as a symbol which has nothing to do either with the territory of the FYROM or with the ethnic Macedonians, or better to say, with Macedonia’s Slavs.[16] The Greeks are clear in this matter having a position that the history and culture of the ancient Macedonians does not belong to the historical and ethnic heritage of the FYROM but quite contrary, they belong to the Greek (Hellenic) inheritance. Therefore, the use of the “Sun of Vergina” by the FYROM authorities is seen by Greece as an act of falsification of history and a cultural aggression on the state territory of Greece with unpredictable political consequences in the future. That is the same as well as with the cases of naming certain institutions and public objects with the names of Philip II (national soccer stadium in Skopje) or Alexander the Great (the highway in the FYROM and the Skopje airport) or with erections of the monuments devoted to them (on the main city square in Skopje).

The Embargo and Further Negotiations

In 1993 several states recognized Macedonia under the official state-name as the FYROM but there were also and those states who recognized the country as the Republic of Macedonia. Macedonia was recognized by six EU members followed by the United States of America (the US) and Australia by early 1994. However, the Greek Government experienced Macedonia’s recognition of independence without the final fixing the question of Macedonia’s administrative name for the external usage as her own great diplomatic and national defeat, and as a response to such situation, Athens imposed a strict trade embargo to the FYROM on February 17th, 1994 for the sake to more firmly point out its unchanged position regarding several problematic issues in dealing with its northern neighbour. The embargo had a very large, and negative, impact on Macedonia’s economy as its export earnings became reduced by 85% and its food supplies dropped by 40%. On the other side, the economic blockade was very much criticised by the international community including and the EU and, therefore, not much later became lifted in 1995, but after successful negotiations between Greece and the FYROM, when these two countries finally recognized each other and established diplomatic relations. The FYROM, as a part of a settlement package with Greece, was also forced to change the official flag of the state on which the “Sun of Vergina” was replaced with the “Macedonian Sun”.[17]

However, the negotiations between the FYROM and Greece in regard to a permanent state-name of Macedonia are still being conducted by the UN, and this problem is not solved properly up today on the way that the both sides are going to be fully satisfied. The issue arose several times concerning the FYROM possibility to join both the NATO and the EU as Greece (member state of both organizations) threatened to use a veto right in order to stop Macedonia’s admission if previously the problem of Macedonia’s state-name is not solved in the Greek favour. Talks between the FYROM and Greece are permanent up to now with some new alternative state-name proposals by both sides as, for instance, the Constitutional Republic of Macedonia, the Democratic Republic of Macedonia, the Independent Republic of Macedonia, the New Republic of Macedonia and the Republic of Upper-Macedonia.

Nevertheless, the talks proved that no one of these proposals is acceptable for both parties. The FYROM proposed as a workable solution to use changed state-name only in relations to Greece, but at the same time to keep its constitutional state-name in all other international relations. However, even this proposal did not lead to a final and sincere solution as Greece insisted that a final deal must be applied internationally. The UN mediator’s compromising proposal to rename the state was as the Republic Macedonia-Skopje. Nevertheless, despite all possible efforts that were made to solve the problem, no agreement could be reached so far and, therefore, the NATO and the EU memberships of the FYROM are very problematic as one of the membership requirements is to reach agreements with Greece on all disputable political questions including and the official Macedonia’s state-name.[18]

Concluding Remarks

It is quite remarkable that a dispute between the FYROM and Greece on Macedonia’s official state-name after 1991, which looks probably quite trivial on the first sight, can have so large political and other implications with unpredictable consequences in the future. One can wonder how Greece and the FYROM became firmly stuck to their positions for a quarter of century. However, the very fact is that this dispute is actually directly connected with their national identities and cultural inheritance.

Sources

Georges Castellan, History of the Balkans from Mohammed the Conqueror to Stalin, New York: Columbia University Press, 1992.

Loring M. Danforth, “Claims to Macedonian Identity: The Macedonian Question and the Breakup of Yugoslavia”, Anthropology Today, 9 (4), 1993, 3−10.

Nicolaos K. Martis, The Falsification of Macedonian History, Athens: Graphic Arts, 1983.

James Pettifer (ed), The New Macedonian Question, New York: Palgrave, 2001.

Hugh Poulton, The Balkans: Minorities and States in Conflict, London: Minority Rights Publications, 1994.

Victor Roudometof, “Nationalism and Identity Politics in the Balkans: Greece and the Macedonian Question”, Journal of Modern Greek Studies, 14 (2), 1996, 253−301.

Notes

[1] James Pettifer (ed), The New Macedonian Question, New York: Palgrave, 2001, 15−27.

[2] The term Macedonia is of the Greek origin.

[3] This day is celebrated in the FYROM as the Independence Day.

[4] James Pettifer (ed), The New Macedonian Question, New York: Palgrave, 2001, xxv.

[5] Nicolaos K. Martis, The Falsification of Macedonian History, Athens: Graphic Arts, 1983.

[6] Bulgaria never recognized separate Macedonian nationality, language and alphabet. For Bulgarians, all Macedonia’s Slavs are of the Bulgarian origin. Greece is recognizing only the existence of the Macedonian Slavs but not on its own territory where all Slavs are considered as the Slavophone Greeks [Hugh Poulton, The Balkans: Minorities and States in Conflict, London: Minority Rights Publications, 1994, 175].

[7] Greece is a member of the EU from 1981.

[8] The Constitution’s day of adopting is November 17th, 1991 and day of entry into force November 20th, 1991.

[9] At that time it was the European Community which became next year the European Union.

[10] Victor Roudometof, “Nationalism and Identity Politics in the Balkans: Greece and the Macedonian Question”, Journal of Modern Greek Studies, 14 (2), 1996, 253−301.

[11] Loring M. Danforth, “Claims to Macedonian Identity: The Macedonian Question and the Breakup of Yugoslavia”, Anthropology Today, 9 (4), 1993, 3−10.

[12] The territory of the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (the FYROM) is also known as the Vardar Macedonia, contrary to the Macedonian territory in Bulgaria – the Pirin Macedonia, and in Greece – the Aegean Macedonia. A geographical-historical territory of Macedonia became divided between Greece, Serbia and Bulgaria as a consequence of the Balkan Wars of 1912−1913: “…Bulgaria who had only a little piece of Macedonia in her share: the Struma Valley between Gorna Dzumaja (Blagoevgrad) and Petric with the Strumica enclave. Greece received all Macedonia south of Lake Ohrid and the coast with Thessalonika and Kavala. Serbia was given Northern Macedonia and the center up to Ohrid, Monastir (Bitola) and the Vardar” [Georges Castellan, History of the Balkans from Mohammed the Conqueror to Stalin, New York: Columbia University Press, 1992, 381]. In essence, Greece received 60%, Serbia 30% and Bulgaria 10% of the geographic-historical territory of Macedonia. A Present-day FYROM is in fact the Vardar Macedonia that became annexed by the Kingdom of Serbia in 1913 known in Titoist Yugoslavia as the Socialist Republic of Macedonia with the capital in Skopje.

[13] The Greeks are not the Slavs.

[14] Loring M. Danforth, “Claims to Macedonian Identity: The Macedonian Question and the Breakup of Yugoslavia”, Anthropology Today, 9 (4), 1993, 3−10.

[15] Victor Roudometof, “Nationalism and Identity Politics in the Balkans: Greece and the Macedonian Question”, Journal of Modern Greek Studies, 14 (2), 1996, 253−301.

[16] Loring M. Danforth, “Claims to Macedonian Identity: The Macedonian Question and the Breakup of Yugoslavia”, Anthropology Today, 9 (4), 1993, 3−10.

[17] The Greeks in the Aegean Macedonia are using regularly a blue flag with the “Sun of Vergina” which is also in many cases put on the state flag of Greece as a historical amblem of the North Greece.

[18] The FYROM is currently a candidate state for the EU membership together with Turkey, Serbia and Montenegro.

All images are from the author.