The Rights of America´s Veterans: Protests of Bonus Army ¨Were Not In Vain; Their Effort Led To The GI Bill of Rights

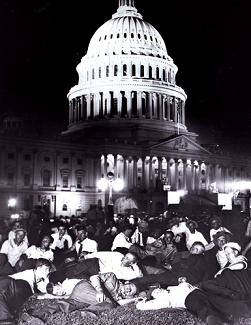

As the World War I “Bonus Army” veterans and their families scattered under clouds of vomiting gas fired by the U.S. Army to clear them out of their shantytowns near the U.S. Capitol that July day in 1932, they might well have thought that their protests were in vain. Seventeen thousand veterans as well as their family members, friends, and supporters were routed from their tent city on the order of U.S. Attorney General William Mitchell. No less a figure than World War I hero General Douglas MacArthur led foot soldiers against them, backed by six tanks, with World War II hero-to-be Major George Patton astride his mount at the head of the cavalry. The squatting veterans were driven out and their shacks and tents and their possessions were torched on orders of a government defiantly opposed to their demand for early payment of “Service Certificates” for World War I duty issued by Congress in 1924 but not redeemable until 1944. A large segment of the U.S. population suffering the hardships of the Great Depression was sympathetic to the veterans, including the outspoken U.S. Marine Corps General Smedley Butler, shortly to become famous for his opinion “war is a racket.”

Seymour Langer, a suburban Chicago radiologist whose father may have served in the army during WWI, often spoke of the futile effort of the tear-gassed veterans to get paid and told his son, Adam, a writer, that he was considering writing a book on the subject. At one point, Seymour wrote historian Barbara Tuchman asking if she thought a book on the Bonus March was a good idea and she replied telling him, yes, to write the book. Years passed, though, and when Dr. Langer died in 2005 at age 80 he had never found time even to begin his project. Yet the very thought of it fascinated Adam, who had fantasized of accompanying his dad on research trips to mine information for the book. Adam, with the novels “Ellington Boulevard” and “Crossing California” to his credit, had never before written a work of nonfiction. Today, Langer told The Los Angeles Times, his new book, “My Father’s Bonus March” “is the story of what we didn’t do together, of the conversations we didn’t have, of the projects we didn’t finish, of the stories he left out, of the inner life, about which I knew so little, of what our relationship could have been but wasn’t.”

In a wide-ranging television interview with Lawrence Velvel, dean of the Massachusetts School of Law at Andover and host of the Comcast broadcast “Books of Our Times,” broadcast nationally, Adam Langer said that some of his father’s stories may have been made up or embellished, such as the one that grandfather Sam Langer served during the Great War. “Nobody I talked to—cousins, uncles, my father’s broker or friends ever heard of him serving in the military (and when) I looked into that story I could find no verification for it.” When he tried to verify that story at the National Archives Adam discovered many of the records from that period were burned and so he cannot be sure if Sam ever served or if his father contrived the tale to explain his interest in the Bonus March. Such ambiguities deepened the mystery and the challenge of writing the book.

Adam speculates that his father’s interest was fueled by the fact he was the only member of his inner circle of friends that did not see service in World War II and “he thought that these veterans should be honored.” In fact, the historic GI Bill of Rights enacted in July, 1944, was in significant part a nation’s belated response to the failure of past administrations to do right by its veterans such as those who served in the horrific World War. Adam thought that the quest to discover his father’s reasons for being interested in the Bonus March prompted him to “keep looking, keep searching for what’s not being told.” He goes on to say, “And that’s what I got out of it. Whether he intended to give me that message or not, what I got out of it was ‘Here’s something left out of the history books and your job is to find out what’s missing and to put together the pieces on your own,’ and that’s what the book was about for me.” Adam said his father told him the Bonus March was “the most overlooked incident in American history.” He added that he wanted to view his father’s life “through the lens of the Bonus March, and to see what had been forgotten that he thought should be remembered, at the same time seeing what I thought might be forgotten about his life, and seeing what should be remembered about that.”

Langer says the Bonus March was largely forgotten because, first, it reflects very poorly on some individuals Americans view as heroes, notably MacArthur and Patton, but also on Dwight Eisenhower, who was elected President in 1952 but then served as liaison officer for the Army with the District of Columbia police force. Second, Langer said, Americans, particularly Jewish Americans, see President Franklin Roosevelt as a heroic figure, but after taking office in 1933 he vetoed the bonus bill several times. The bill was finally enacted over his veto “so he doesn’t come off so well in that story,” Langer says. “It contradicts the story that Roosevelt comes along and saves the day.” Third, “It’s a story of American heroes fighting American (war) heroes, veterans against the Army.” Fourth, the Bonus Army was integrated “and that was long before the racial integration of the Army, and that’s a story that hasn’t been told.” “The Bonus March didn’t fit the American history narrative,” he said. “It was an ignominious incident in American history, in which veterans of World War I were essentially being smoked out by the current cavalry.” Adam said he learned from his father’s interest in the Bonus March that “the little guy doesn’t always make out so well, but you can’t really throw up your hands about that.” His father’s message was to “keep moving, keep working, keep persevering. The Bonus March ended very poorly for a lot of people but the bonus bill eventually did pass, and it led to the passage of the GI Bill” (in 1944.)

Langer says to learn more about his father’s fascination with the Bonus March he tried to interview “everyone from every step of the way of my father’s life, from the people he knew in his childhood to a high school girlfriend. “The idea of solving anyone’s history through anything, or defining a person through any sort of incident, is kind of a foolhardy mission, and one can never truly solve it.” Langer adds that he was inspired to write the book in part by the movie “Citizen Kane” which examined the inner life of a newspaper mogul whose last utterance on his death bed was “Rosebud”—-`which turned out to be the brand name of the sled he used as a child. Trying to get at the reasons for his father’s interest “led me into a lot of paths, and allowed me to find a way of talking to a lot of people who knew him and who knew about the history. (While) I feel that I know him a little bit better, he’s still very much a puzzle.”

Doing his research, Langer says he discovered his father “liked putting on roles and playing a role” and also that he was “a very warm and generous person” who, even as a kid, “was a very strong guy with a forceful personality who knew what he wanted and didn’t suffer fools gladly.” “If he was in a restaurant he didn’t want to wait more than a minute (to be served) otherwise he was out the door. He liked to play the role of the gruff individual, comparing himself to (the actor) Lionel Barrymore.” He describes his father as a self-made man who was “quite satisfied with his life. He had a job that he liked, he had a family, he had a wife, he had a nice house in West Rogers Park. In some way, from the boy who’d grown up with a physical handicap (he overcame a crippling hip condition he was born with that required him to use crutches for much of his childhood) in kind of tough times on the West Side, I don’t think he thought that was such a bad deal.”

Langer also discovered that his father had neglected to tell him much about his life on the old West Side of Chicago, a place he imagined where seltzer water was sold as “two cents plain” and boys played stickball in the streets, and families to escape the intense summer heat would sleep in the parks. “There was (also) a lot of pain in that story and my father didn’t lead as much of an idyllic life” and had to work himself out of that area to move up, so “he studied, studied, studied and became a doctor and left that world behind.” “There was a lot of nuance there that didn’t get told because it didn’t fit the narrative,” Langer says, “just as the bonus march didn’t fit the American history narrative.”

Whether the Bonus March fit into the American narrative or not, it indisputably set the stage for enactment of the GI Bill of Rights, widely regarded as the most positive and uplifting piece of legislation since President Lincoln emancipated the slaves.

The Massachusetts School of Law at Andover, sponsor of the broadcast “Books of Our Times,” was purposefully founded in 1988 to help students from minority, immigrant, and low-income households obtain a rigorous, affordable legal education. The law school also sees as its mission providing the public with information on the important issues of the day. To comment on this article or to obtain further information on the law school, contact Sherwood Ross, media consultant to the law school. Reach him at [email protected].