The New Shape of the Struggle in Egypt

report from Cairo on the mass protests on May 27

Mostafa Omar reports from Cairo on the mass protests on May 27–a breakthrough for the left after several months of religious strife and anti-strike propaganda.

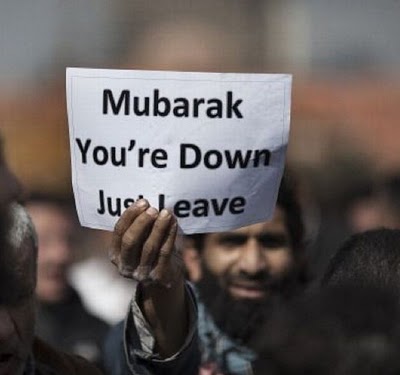

As many as 1 million people gathered in Cairo’s Tahrir Square and across Egypt May 27 for a “Friday of Anger” that showed that the revolution against dictator Hosni Mubarak and his regime has reached a new stage.

The May 27 demonstrations were called by left organizations in defiance of Egypt’s military rulers–as well as the Muslim Brotherhood and liberal groups that were part of the mass protests against Mubarak in February.

Despite a scare campaign in the official media–and most of the liberal media as well–aimed at steering people away from the protests, the turnout was huge in Cairo, and even bigger in Egypt’s other main city of Alexandria, where at least 500,000 people marched. Tens of thousands rallied in Suez, Port Said, Mansoura and many other cities.

In Tahrir, the militant crowd spent the day chanting, listening to speeches, and engaging in lively discussions about the nature of the revolution, and what should be done about the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, the military body that has ruled Egypt since Mubarak’s ouster. The spirit of revolution was in the air–the demonstration was reminiscent of Tahrir in the days before Mubarak’s fall.

Families of the martyrs and those injured in the uprising spoke at the rallies, and victims of military torture and the regime’s tribunals told their stories. Speaker after speaker talked about how the Supreme Council is trying to contain the masses’ demands for democracy and equality, and the revolution must continue.

The new “Friday of Anger” on May 27 announced that the struggle is continuing in Egypt, but now, it is against the country’s military rulers who have refused to grant many of the revolution’s demands for democracy and who have tried to demobilize the movement through a combination of some concessions and reforms and renewed repression.

The future of Egypt’s struggle will depend on whether the forces that participated on May 27 can continue to meet the urgent task of bringing wider layers of people into the fight–and build an alternative to the Supreme Council and its supporters, including the liberal organizations that were once sympathetic to the revolution.

A rally reshapes the political map

IN THE two weeks prior to the May 27 rallies, the issue of support for or opposition to the planned demonstrations dominated the media and polarized the country.

On the one hand, the Supreme Council issued press statements insinuating that some organizers of the protests intended to foment chaos and civil war. The media, both official and liberal, mainly toed the line of the Council–many reporters and commentators claimed the protesters are actually planning an armed uprising, rather than a peaceful demonstration.

Rumors spread that thugs and provocateurs would carry out widespread of acts of vandalism, that banks would close their ATMs, and that Hardee’s and Kentucky Fried Chicken would close their Tahrir Square franchises Friday in anticipation of rioting. Multinational firms sent e-mails to employees telling them to avoid going near protest spots.

On the day before the protest, police arrested three activists for distributing leaflets and posters critical of the Supreme Council, and handed them over to the military, which in turn detained them for 12 hours.

The powerful Muslim Brotherhood organization, whose members participated in the revolutionary uprising back in January and February, declared its opposition to the rally.

It issued a statement in support of the Supreme Council in which it denounced May 27 organizers as “counterrevolutionary,” and accused them of conspiring against the army. In Alexandria, Brotherhood supporters launched a red-baiting campaign, distributing thousands of leaflets that accused anyone who would demonstrate against the Supreme Council as being “communists and secularists”–code words for those who would propagate atheism.

Other more hard-line fundamentalist groups–known collectively as Salafists–also declared that they would not participate in the demonstration.

But organizers for the “Friday of Anger” also had reasons for feeling emboldened in the days before May 27. One critical factor was the Supreme Council’s concession on the prosecution of Mubarak.

In April, in response to tremendous popular pressure, the Supreme Council announced that Mubarak would go on trial for corruption and theft–his sons have also been accused. But the Council refused to make him stand trial on more serious charges of killing peaceful protesters. This dodged the issue of having to put the handcuffs on their former boss–Mubarak was allowed to remain under treatment for a heart condition in a five-star hospital in the posh tourist destination of Sharm el-Sheikh.

But the move was rejected among the mass of the population–and thus, in an unexpected move, Egypt’s attorney general announced on May 24 that Mubarak would go on trial for conspiring with the former Interior Minister to kill more than 865 people and injure thousands of others during the revolutionary uprising from its beginning on January 25 until Mubarak’s resignation on February 11.

The Supreme Council’s change of heart to try Mubarak for murder and not just financial corruption was typical of previous concessions to mass pressure since it took power in February.

First, the Council drags its feet and tries to shield corrupt and brutal businessmen and politicians as long as it can, so as to salvage as much of the old regime as possible. Then, when millions begin to question why the army is being so soft Mubarak-era figures and threats of marches and protests in Tahrir and elsewhere after Friday prayers begin to grow, the Council hastens to make concessions in an attempt to absorb popular outrage.

In this case, organizations frustrated with the Council’s timidity in holding trials for Mubarak and his entourage planned a new protest for May 27–called the “Second Friday of Anger” in reference to the mass demonstrations that shook the Mubarak regime on Friday, January 28 and on a weekly basis in the days that followed. But this time, the protesters’ target would be the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces.

In the days immediately leading up to the rally, aside from the arrest of the three activists, the government adopted a more conciliatory tone toward the protests. The Council announced that it respected the right to peaceful protest and vowed that the military would never open fire on the Egyptian people. Also, Egyptian Prime Minister Essam Sharaf declared that workers’ frustration over low wages was legitimate, and that he unconditionally supports peaceful protests.

The message of May 27

Organizers of the “Friday of Anger” said they were demanding that the Supreme Council: 1) try Mubarak for murder; 2) end the use of military trials against activists and revolutionaries; 3) abandon its authoritarian monopoly over major issues in the transition to a democratic system; and 4) begin a process of redistributing the country’s wealth toward the poor by setting a living minimum wage.

The demonstrations were a huge success–and, considering all the attempts to derail them, a blow to the Council and its supporters, including the Muslim Brotherhood.

In spite of the absence of the Brotherhood, the rallies were the largest show of force in weeks by left and liberal forces in the country that support a continued struggle for real democracy and social justice.

In the early hours of Friday, young people who organized themselves in public safety committees secured the entrances to Tahrir Square, as had happened during the early days of the revolution–searching participants to weed out provocateurs or thugs. As the day wore on, speaker after speaker talked about the failures of the military to honor the demands of the revolution, and declared their opposition to military trials and the “kid gloves” treatment that Mubarak and his cronies have gotten.

The crowd chanted over and over about the Muslim Brotherhood’s betrayal: “Where is the Brotherhood? Here is Tahrir!” The protests all ended peacefully, with thousands reserving the right to come back and reoccupy Tahrir in the future if necessary.

On Saturday morning, all the newspapers and TV stations had to report on the large size of the turnout and the peaceful nature of the mobilizations. Millions who were subjected to a weeklong campaign of scaremongering discovered that those who organized the rally had the best interests of the revolution at heart.

Religious vs. class polarization

For those who want to unite everyone interested in continuing Egypt’s democratic revolution, the May 27 rallies were a big step forward in many ways.

With counterrevolutionary propaganda and religious strife dominating the political scene for almost two months, the rallies’ success could give confidence to workers’ and democratic struggles.

Throughout April and May, the government and the media outlets that support it carried out a propaganda campaign against demonstrators, in particular, singling out striking workers. Those who protested or struck were accused of paralyzing the country and wrecking the economy. This led to a retreat in workers’ confidence to strike for their rights–strikes and sit-ins fell to 30 actions in April, compared to hundreds in each of the previous two months.

Meanwhile, reactionary Salafist groups spent this period agitating and inciting hatred against Christians, who make up 15 percent of the population. For example, in March, Salafists, along with the Muslim Brotherhood, turned a referendum on changes to the Mubarak-era constitution into a religious conflict. The vote was imposed undemocratically by the Supreme Council to avoid drafting a new constitution.

Fundamentalists of all sorts mobilized millions to support nine changes to the old discredited constitution, which itself maintains that Islamic Sharia is the main source of laws in the country. In the weeks leading up to the referendum, the fundamentalists insisted that good Muslims would vote “yes,” and only bad Muslims and Christians would vote “no.”

More seriously, Salafists attempted to incite religious hatred against Christians in Friday prayer sermons, and by holding provocative rallies outside of churches. Wild rumors were spread, claiming that the Coptic Church kidnaps Christian women who marry Muslims and convert to Islam. Different Salafist groups also pledged “jihad” to stop the government from meeting Christians’ demands to reopen more than 50 churches closed arbitrarily by Mubarak.

As a result of this intense Salafist agitation, a number of anti-Christian riots broke out in different parts of the country.

First, in early March, in the village of Atfih, south of Cairo, a mob of Salafists, along with disenfranchised urban poor, burned a Coptic church to the ground because of an alleged relationship between a Christian man and a Muslim woman.

In April, in the Southern governate of Qena–which has a large number of Christian residents–Salafists organized civil disobedience to oppose a new governor for the province on the basis of his Christian identity. In fact, many Christians and Muslims opposed the appointment of Emad Mikhael because he was a notoriously brutal general in the secret police under Mubarak. But the Salafists directed their wrath on the appointed governor’s religious faith.

More recently, in early May, in the impoverished neighborhood of Imbaba in Cairo, another Muslim mob attacked and burned a Coptic Church. Salafists had been agitating against Christian s for some time, and claimed that priests were holding a Christian woman married to a Muslim man in the church against her will. As army and police officers stood by, gunfights between Muslims and Christians broke out. They lasted for hours and left at least 11 people dead.

Fortunately, a public outcry by a sizeable majority of ordinary Muslims and Christians against church burning temporarily slowed down the Salafists.

For example, mass demonstrations against religious sectarianism took place across the country on May 13, and forced many Salafists to disown the attacks. Also, street demonstrations and sit-ins by thousands of Christians–against church burning and for equal rights–outside of the Radio and Television Building in Cairo and elsewhere have sent a strong message that Christians are ready to fight back.

In this context, the importance of the May 27 demonstrations in focusing demands on the Supreme Council, not religious issues, is very important–they can help to refocus the attention of the majority of workers and the poor on class and political issues, away from religious sectarianism.

Who leads the counterrevolution?

As a result of the sectarian violence clearly organized to derail the revolutionary unity forged during the uprising against Mubarak, millions of people in Egypt are aware that counterrevolutionary forces are at work.

But answering the question of who leads them in Egypt today–given the fluidity that comes with any revolutionary situation–is very confusing.

There are plenty of explanations floating around. Some believe Mubarak runs the counterrevolution from his hospital bed in Sharm el-Sheikh. Others insist that the “remnants” of Mubarak’s National Democratic Party stand to lose the most from the revolution. Many people recently focused on the Salafists. A minority mistrusts the Supreme Council.

Do these explanations hold up?

The questions get even more confusing because of the new roles played by both liberals who were former opponents of the regime and–it gets worse–former supporters and functionaries of the old regime who have reinvented themselves as uber-revolutionaries. Many Egyptians refer to this new category of individuals as the “colorful people”–because they are chameleons, so to speak.

Now, many of the old liberal opposition figures and the “colorful people” have formed an unholy alliance. Together, they have directed their condemnations against democracy protesters and “selfish” striking workers who, they charge, want to wreck the economy and destroy the revolution.

But as for the question of who is leading the counterrevolution, it is certain that Mubarak is helpless and gone forever from the political stage. If he lives for a few more months, there is a good chance that he will be hanged.

On the other hand, there can be no doubt that many officials from Mubarak’s party, as well as former secret police officers, are attempting to wreak havoc and incite civil war.

As for the Salafists, the events of the last few weeks have shown that those who opposed the January 25 movement and sided, in typical fashion, with the ruler–previously, it was Mubarak, and now it is the military–have proven to be dangerous counterrevolutionary shock troops.

Likewise, the Muslim Brotherhood, whose members participated in the uprising, has broken off whatever relationship it had with the revolutionary forces and is increasingly playing a counterrevolutionary role by opposing workers’ strikes and demonstrations designed to put pressure on the Supreme Council.

But the fact remains that the principal enemy of the revolution was and remains the social class whose economic interests are directly threatened by this ongoing revolutionary upheaval: Egypt’s capitalist class.

The Egyptian capitalist class–known to many Egyptians as the “class of businessmen”–amassed untold wealth through a system based on high levels of exploitation of Egyptian workers and peasants, backed by a brutal and repressive state apparatus led by Hosni Mubarak.

As a result of this, a small minority of rich Egyptian families controls much of the country’s wealth, while millions of Egyptians barely survive, living in abject poverty. There’s no doubt that the general misery suffered by the majority of the Egyptians in the last 30 or so years was the key underlying factor in the outbreak of the January 25th revolution.

Therefore, the future of the Egyptian revolution will be decided, ultimately, by which class comes out on top. The question is: Can Egypt’s “businessmen class” regain control over society by squelching all revolutionary impulses and struggles, or will the workers and peasants of Egypt develop the consciousness and level of organization needed to forge an alternative to the businessmen’s system?

Egypt’s capitalists have been busy attempting to figure a way out of their crisis–and they have a number of tools at their disposal. First and foremost, the businessmen want Mubarak’s generals to operate as an emergency executive committee to defend their interests.

So far, the generals have attempted to do just that, but with varying degrees of success. For example, the campaign to blame strikes for the collapse of the economy, backed by the “colorful people” and many liberals, has led to a drop in the number of strikes. But workers are still organizing protests after their shifts end.

The generals also periodically crack down hard. Some strikes have been outlawed, and the head of the new independent Transport Workers Union was put on trial. Some protests have been repressed–the military even used live ammunition against a peaceful demonstration outside the Israeli embassy on May 15, the anniversary of the Palestinian Nakba. Three people were killed.

But the movement has answered back–most recently, with the mass demonstrations on May 27.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Can Egypt return to January 24?

Despite its repressive measures, the Supreme Council understands that the January 25 uprising has changed Egypt once and for all in certain ways. The generals understand the depth of revolutionary feelings among the poor, and they therefore have no intention of trying to return to the way the regime operated before January 25. The goal is to get a new set-up that preserves the interests of the businessmen.

The Council aims to reform the political and economic system, allowing it to become more democratic and less oppressive. But of course, it has no intention of abandoning the basic tenets of capitalism in Egypt. Its strategy revolves around a combination of offering some concessions–always under pressure–while attempting to repackage the economic priorities of the old regime.

So, for example, in mid-March, under the pressure of thousands of protesters storming the headquarters of the secret police in cities around the country, the Council formally dismantled this apparatus. But it then rehired some of the same brutal officers in a new National Security Administration.

The Council dismantled Mubarak’s New Democratic Party, but it has allowed thousands of corrupt officials to continue to control hundreds of local municipalities.

And while the generals formally affirm their respect for human rights and the right of citizens to peacefully protest, it has actually arrested many activists and tried them in military courts on a number of occasions. Some army officers have tortured detained activists in incidents similar to practices typical of the Mubarak era.

Also, as a result of big demonstrations in mid-May to support the right of return for Palestinian refugees and demand that the Egyptian siege of Gaza be lifted, the Council permanently reopened the Rafah border crossing to Palestinians. Still, the Council continues to sell natural gas to Israel and receive high-level Israeli officials in Cairo.

Economically, the generals and the businessmen have made concessions to workers’ demands for higher wages. But they have no intention of changing the economic policies and priorities of the Mubarak era. On the contrary, the council has said it would continue the neoliberal policies of privatization of the Mubarak era–the same policies that led to the impoverishment of the masses.

For example, the richest man in Egypt, Naguib Sawiris, publicly opposed even a discussion of introducing a progressive income tax system to raise government revenue. Meanwhile, Prime Minister Essam Sharaf has asked the IMF for a new $12 billion loan–which will only deepen the country’s debt crisis.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Revolution vs. Counterrevolution

High workers’ expectations for a better life after the revolutionary uprising continue to place tremendous pressures on the cabinet and the Supreme Council. Millions of industrial workers, government employees and their families are waiting for Sharaf to fulfill his promise to set a living minimum wage this summer.

Despite the relative lull in strikes during April and May, significant workers’ struggles are continuing.

For example, former workers for the Omar Effendi department store chain, which was privatized a few years ago and sold dirt-cheap to a foreign investor who shut it down, won a key court order to re-nationalize the company and have regained their jobs. Textile workers in Shebeen Al-Koum, a city in the industrial Delta region, continue a brave struggle, also for re-nationalization.

Government workers in the Department of Antiquities continue to threaten to close down the Egyptian Museum if their wage demands aren’t met. Plus, workers for a number of Suez Canal companies are continuing a three-month sit-in against outsourcing.

And on May 16, thousands of doctors in public hospitals went on strike across the country to win wage increases. Even more significantly, the doctors are demanding an increase in government expenditures on health care from 4 percent of gross domestic product to 15 percent–in order to create a more humane health care system for a population plagued by diseases such as Hepatitis C and heart disease. Pharmacists are to take a vote for a nationwide strike set for mid-June.

The ideological campaign against workers and strikes has begun to break down somewhat. Sharaf said in a recent televised speech, “Workers’ demands are legitimate human aspirations from people who suffered so much for so long.”

Meanwhile, the newspaper Al-Ahram admitted on May 28 that the economy is not actually in a state of collapse as previously alleged by commentators who support the Council’s criticisms of strikes. In fact, industrial production actually grew in the first quarter of 2011 compared to the first quarter of the previous year.

The decrease in strikes shows that workers are continuing production, but they are in a wait-and-see position. Their struggles could return at a much higher pitch if, for example, the government fails to raise the minimum wage.

At the same time, rising food prices are putting a strain on workers and the poor. The cost of staples like beans and rise has jumped in recent weeks by 30 to 100 percent. Such conditions are also giving rise, along with questions of democracy, to the dissatisfaction expressed on May 27.

The stage is set for a new phase in the revolution, and in this new period, people will continue to develop a clearer understanding of key political questions: the nature and motives of the generals, the class interests of the Muslim Brotherhood and Salafists, who the economic system really serves.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

The left attempts to organize an alternative

Back in February, the Revolutionary Socialists published a highly controversial article titled “The Supreme Council leads the counterrevolution.” The article highlighted the fact that the generals control 25 percent of the economy and have interests antithetical to those of the working masses, despite the Council’s lip service to safeguarding the aims of the revolution.

At the time, many radicals and people who participated in the uprising criticized this statement as wrong at best, and reckless at worst. Many activists still harbored a conviction that the generals had proven to be on the side of the revolution by ousting Mubarak, and that they could be trusted to do the right thing. Only a handful of socialists and revolutionaries insisted that, because of their class position, the generals were not a revolutionary force.

However, the betrayals of the Supreme Council toward issues of democratic change over the last three months have led thousands of young people and workers to begin to question which side the Council is on. It is no longer considered taboo to at least criticize the Supreme Council.

Nevertheless, all the forces on the revolutionary left in Egypt realize that larger formations are needed in order to connect with the struggles ahead and play a role in challenging the bosses and the generals, as well as their supporters among the liberal opposition and the Muslim Brotherhood.

The left has begun to organize structures to prepare itself for the coming months. For example, workers succeeded in the last three months in winning some key battles to form independent unions. Postal workers, transport workers, temp workers and others have formed more than 13 independent unions, and others are in the process of forming.

More than 2,000 militant workers, socialists and radical activists have joined the new Workers Democratic Party, which has a radical anti-capitalist platform. Similarly, more than 3,000 leftists, socialists and activists have formed the Socialist Popular Alliance Party with a radical pro-worker program.

Two weeks ago, four revolutionary groups came together to form the Socialist Front–an alliance to coordinate their tactics in the struggles to come.

Still, the revolutionary left has an urgent task of growing in numbers and building wider layers of fighting cadre who can stand up for a socialist alternative within the working class movement.

The polarization that took place over the May 27 protests reflects a serious division between those social and political forces that want to continue the revolution until it accomplishes its basic democratic and social goals, and those forces that want to go back to business as usual.

As the Muslim Brotherhood and Salafists continue to expose themselves as pro-authority and big business, the left will have a further opportunity to grow–if it further develops its tactics and spreads its influence. In fact, at the May 27 demonstration in Tahrir, thousands of people bought socialist newspapers and other revolutionary literature for the first time. This reflects a big opening for socialist politics–despite the negative legacy of Nasserism in the 1960s and its claims to stand for socialism.

The left is on the right track by focusing on building struggles, building its numbers and building unity. It needs to use all of this to pressure the Council and its supporters in the coming few months, while avoiding premature confrontations.

What you can do

Hossam el-Hamalawy and two other left-wing journalists have been summoned to appear before military judges on May 31. Go to the Mena Soldarity Network [1] website for more information and to endorse a statement opposing the harassment of these journalists.

Hear Mostafa Omar at Socialism 2011 [2] in Chicago, speaking on “Egypt: The revolution continues.” Check out the Socialism 2011 [3] website for more details.