The Nanjing Massacre of 1937: The Film

By the Japanese High Command with an introduction by Mark Selden

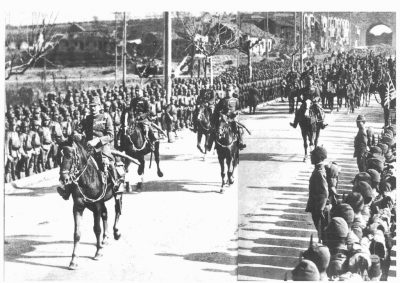

Featured image: Japanese high command enters Nanjing on horseback (Source)

On December 14, 1937, the day after Japanese soldiers entered Nanjing, a crew led by producer Matsuzaki Keiji, under the guidance of the Military Special Affairs Department, entered the city. Its mission: to document the transition to Japanese rule in the Nationalist capital.

The next day they began shooting a documentary film, Nanjing [Nanking] that presents the battle as framed by the Japanese high command. The crew had just completed an earlier documentary, Shanghai, on the battle that paved the way for the advance of Japanese forces toward Nanjing. Dispatched to Nanjing without supplies, the reign of terror began en route with Japanese forces attacking villages en route to secure food and supplies. In Nanjing, shooting of the film continued to January 4, 1938 and the film was rushed to completion for release in Japan on January 20. (Can it also have been distributed for viewing in Chinese cities? Or for international distribution?) Long believed to have been lost, a print was discovered in Beijing in 1995, although with 10 minutes of the original missing. Nippon Eiga Shinsha made it available as a DVD. The present film superimposes primitive English translation . . . whether provided at the time of its release or years later, presumably for international distribution.

Toho film on Nanjing Massacre made 1938; English subtitle

Prepared five years before Frank Capra’s seven part American series “Why We Fight” (1943), and also drawing on Leni Riefenthal’s Triumph of the Will, Nanjing 1937 seeks to portray both the power and benevolence of the Japanese military. It begins with the victory parade of Japanese forces in Nanjing, the high command on horseback with troops marching behind while additional Japanese troops line up along the road to witness the entry. Other shots highlight the destructive power of Japanese weaponry and the benevolence of Japanese forces shown towards Chinese POWs and providing candy to smiling children while yet other Chinese children delightedly set off firecrackers to ring in the New Year. Viewers in Japan were also treated to a long ceremony conducted by General Matsui Iwane honoring the war dead, with Japanese soldiers carrying the ashes of slain comrades even as the Emperor presided over solemn Shinto rites in Tokyo, as zigzag-shaped white streamers (shide) evoking lightening fluttered in the wind.

Gen. Matsui conducting Shinto rites for the dead (Source)

Other scenes include Japanese soldiers rebuilding destroyed parts of the city and the inauguration of the Nanjing Self-Government Committee.

Inaugural ceremony of the Nanjing Self-Government Committee Jan. 1, 1938 (Source)

Needless to say, there is no Nanjing Massacre on display in the Japanese film. Or is there? The film in fact shows the city’s devastation by invading forces as well as the dispirited faces of Chinese refugees. It does not, of course, display captured Chinese soldiers being led off to the river to be shot, still less the rape and killing of civilians.

Viewed against the background of the American Why We Fight series, Nanjing 1937 conveys another powerful impression. The Japanese army, with the power to crush Chinese forces in Shanghai and Nanjing, was an army marching across China on foot, with officers mounted on horseback. In advancing to attack entrenched nationalist forces in Nanjing, the Japanese troops commandeered a small boat and poled across a river, then lifted a rickety 15-meter ladder to send suicide troops to climb it to enter the fortress. In the film, images of a single tank and a handful of trucks underscore the rather limited mechanization of the Japanese military. Fifteen years ago, in a seminar held in the Taihang Mountains of Shanxi, I saw photographs of Japanese troops hauling dismantled cannons to fight in the harsh terrain, each soldier bearing 60 pounds on his back. Similar images such as these in the film help explain why better-informed Japanese commanders were aghast at the Japanese decision to bomb Pearl Harbor, aware of the overwhelming technical superiority of US military forces.

Viewed in conjunction with samples from the American Why We Fight Series or the Nazi’s Triumph of the Will, Nanjing 1937 can stimulate fruitful classroom discussion of the ways in which nations represent their wars, domestically and for global audiences. Students can also draw on the substantial literature on the Nanjing Massacre, the military ‘comfort women’ system, forced labor and other controversies framing the ongoing historical memory debate in Japan, the United States and internationally.

*

Mark Selden is a Senior Research Associate in the East Asia Program at Cornell University, a Coordinator of The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, and Bartle Professor of History and Sociology at Binghamton University.