The March to War against Syria: The Long Shadow of the 2006 Israeli War on Lebanon

Syria has been on the Pentagon’s drawing board for years, largely because of its important geo-strategic placement in the Middle East.

The process of cornering the Syrian Arab Republic started with earlier accusations pertaining to the alleged development of weapons of mass destruction (WMDs). From 2003 to 2004, George W. Bush Jr. even considered using this as a pretext to invade Syria after the fall of Baghdad as “Phase III” of the “Global War on Terror.” These pretexts later gave way to accusations of “Syrian interference” in Iraq as well as the alleged role of Damascus in the 2005 Hariri Assassination in Lebanon.

In 2007, these various allegations evolved towards accusations of support for Fatah Al-Islam near the Lebanese city of Tripoli and, in league with Israel’s Operation Orchard, claims that Damascus was involved, with the support of Tehran and Pyongyang, in a secret nuclear weapons program. The latter was allegedly part of a “Syria-Iran-North Korea nuclear proliferation axis.” Now in 2011-2012, the humanitarian “Responsibility to Protect” (R2P) card is being played.

The road to Damascus goes through Beirut. Washington’s roadmap against Syria always involved Lebanon as a multi-faceted springboard. In fact, Washington and its allies wanted the deployment of UNIFIL troops, mostly comprised of NATO soldiers, being sent to Lebanon to be stationed on the Lebanese-Syrian border in 2006. Feeling threatened, Damascus warned that it would close the borders with Lebanon and the idea was scrapped.

Syria was the main target of the 2006 Israeli attacks on Lebanon. Regime change in Damascus was the key objective. Tel Aviv’s 2006 defeat in Lebanon by Hezbollah and its allies spared Syria from an attack and probably prevented a broader regional war involving Iran and NATO.

It is after the 2006 events in Lebanon that Washington took the initiative to negotiate with Damascus in the diplomatic arena. These attempts lasted up until 2011 and were aimed at de-linking Syria from Iran and the Resistance Bloc or “Axis of Resistance.” During this diplomatic engagement, which attempted to distance Damascus from Tehran, Tom Lantos, Chairman of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives, visited Damascus and warned the Syrian regime to join ranks with Saudi Arabia and the United States against Iran.

Lantos threatened President Al-Assad while intimating that a few years down the road that there would be a new geo-political reality: “Sunni Muslims and not Iran under Mahmoud Ahmadinejad will be in control in the region, and it is to the advantage of Damascus to know which side to be on.”

2007 was slated for an Israeli rematch against Lebanon that never happened. Very telling is the fact that talks of war were also aimed at Syria too. Washington and Tel Aviv also realized that after 2006 they could no longer launch separate wars against Syria and in Iran. Damascus and Tehran would not fight in isolation from one another. A war against Syria would equate to a war with Iran and vice-versa.

Looking through the timeline of events and all the important dates, it would appear that Washington originally had planned on going to war with Iran by late-2007 or in 2008. This is clear from all the statements being made by both sides in 2007 about war preparations. This also roughly fits into the timeline formed by U.S. military exercises, official statements, rumours of war, and General Wesley Clark’s historic 2001 statement (in the wake of the invasion of Afghanistan) that Syria was included in a list of targeted countries for U.S. military intervention on the basis of a five-year military roadmap. The Israeli defeat in Lebanon, however, upset the timeline of the Pentagon’s military roadmap.

In 2007, when all sides were talking about a regional war igniting, Washington and its allies did launch their war. It is in this period that the destabilization and shadow wars against Lebanon, Syria, and Iran commenced. President George W. Bush Jr. authorized the beginning of this shadow war, which included a combination of “colour revolutions” and covert attacks.

In Lebanon, Fatah Al-Islam emerged in the Shamal (North) Governate, imported into the area by the U.S., Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Egypt, and the Hariri-led March 14 Alliance to fight Hezbollah and its allies in Lebanon. In parallel, an intense spy war against Hezbollah and its allies had also begun.

In Iran, the terrorist organization known as Jundullah (established in 2003), intensified its attacks in the province of Sistan and Baluchistan using Afghanistan and Pakistan as launch pads.

The struggle to establish the Special Tribunal for Lebanon (STL) would also intensify and become a factor in the backdrop of the 2008 internal Lebanese fighting between Hezbollah’s camp and Hariri’s camp.

Having failed to launch another war in 2007 or 2008, Tel Aviv would renew talks with Damascus. Under the framework of deepening Syrian-Turkish ties, Ankara would facilitate the indirect talks between Damascus and Tel Aviv. The stumbling block between the Israelis and Syrians, however, would always be Syrian foreign policy and Syria’s membership in the “Axis of Resistance.”

In 2008, events in Lebanon would once again hamper Washington’s agenda. Under the guise of the Siniora government the Hariri camp was actively working on systematically weakening Hezbollah in coordination with the interests of Washington and Tel Aviv. Hariri and his allies had already given their tacit support to Israel during its 2006 aerial bombardment of Lebanon with the hope that Hezbollah would be eliminated as an outcome of the war. The efforts by Hariri’s camp to remove Hezbollah’s Iranian-installed communication network would have crippled Hezbollah logistically and tactically. Finally, the growing internal tensions between both Lebanese sides over the issue would result in the outbreak of fighting in May 2008.

The internal fighting in Lebanon in 2008 would result in a tactical victory on the ground for Hezbollah and a political victory for it and its coalition with the Doha Accord. Hezbollah would defeat the private army that the Hariri camp had been building, keep its communication network, and also gain a veto in the new Lebanese national unity government.

While both Hezbollah and the Hariri camp played down the fighting that occurred between them in 2008, there was much more at stake. A heated secret battle involving intelligence agents from Jordan, NATO countries, and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries took place in and around Beirut. Hezbollah would effectively route these forces. It was in this context that U.S. and Israeli officials would later vaguely comment by describing the events in Lebanon as a “major setback” and “ruining years of work in Lebanon.”

The use of Lebanon via anti-Syrian elements as a political weapon to “roll back Syria” geo-strategically, as proposed by Richard Perle and other neo-conservatives in an Israeli policy paper, had come to a virtual standstill. Walid Jumblatt and his Progressive Socialist Movement would leave the March 14 Alliance and Hariri would also be forced to retract his accusations against the Syrians about the murder of his father in 2005. Hariri would go on to tell the Saudi-owned Asharq Al-Awsat, a mouthpiece for his Al-Saud patrons, in an interview that his claims against Damascus were motivated by politics. He would state: “This was a political accusation and it has finished.”

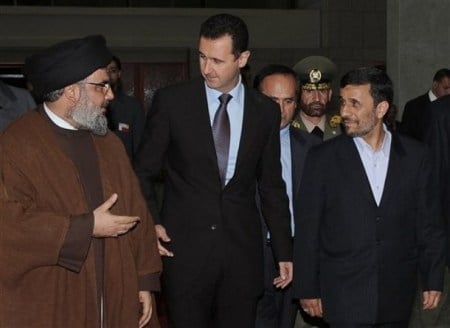

The U.S. withdrawal from Iraq has made removing Syria from the orbit of Iran critical for Washington and Tel Aviv. In 2011, diplomacy was openly cast aside in favour of “regime change.” The groundwork for this probabily started in 2010 after the summit in Damascus between Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Bashar Al-Assad, and Hassan Nasrallah when Washington realized its diplomatic efforts to de-link Syria from Iran were in vain.

While the political dimensions of Lebanon as a springboard against Syria were greatly reduced after Hezbollah’s victory in 2008, the 2009 Lebanese parliamentary elections, and finally the removal of Hariri from the premiership in 2011, Lebanon’s logistical aspects as a base for destabilizing Syria were not given up by Washington and its allies. Segments of the Internal Security Forces (ISF) of Lebanon, which are informally controlled by the Hariri camp, almost certainly were preparing for the use of Lebanon as a weapons hub for the so-called “Free Syrian Army” and other forces from late-2010 to mid-2011.

There is also an increasing and diabolical push to paint the events in Syria along sectarian Shiite-Sunni lines. Syria’s alliance with Iran is being questioned because Iran is a non-Arab country predominantly populated by Shia Muslims and Syria is an Arab state mostly inhabited by Sunni Muslims. This is mere propaganda. Using this logic, those that fiendishly push these talking points would never be able to justify the Saudi, Qatari, Jordanian, and GCC alliances with Turkey, NATO, and the United States under the same standards. These are all non-Arab countries and, aside from Turkey, are predominantly non-Muslim, let alone Sunni Muslim. Yet, the same disingenuous discourse is never applied when speaking about their foreign relations.

In geo-political terms, NATO and GCC support for armed insurgency and civil strife in the Syrian Arab Republic is trying to achieve what the 2006 Israeli war against Lebanon failed to achieve: the surrender of Damascus. Using Syria’s borders with Lebanon, Jordan, Turkey, and Iraq, armed groups are being supplied and supported. Amongst the foreign fighters are members of Fatah Al-Islam from Lebanon and co-opted members of the Awakening Groups, which was initially funded by the U.S. when it was founded in 2005, entering Syria from Al-Anbar, Iraq.

Above: Two of Syria’s allies, Hassan Nasrallah of Hezbollah and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad of Iran, join President Bashar Al-Assad for a summit in Damascus on February 25, 2010.

Mahdi Darius Nazemroaya is a Sociologist and award-winning author. He is a Research Associate at the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG), Montreal. He specializes on the Middle East and Central Asia. He has been a contributor and guest discussing the broader Middle East on numerous international programs and networks such as Al Jazeera, Press TV, teleSUR and Russia Today. His writings have been published in more than ten languages. In 2011 he was awarded the First National Prize of the Mexican Press Club for his work as a war correspondent in Libya. He also writes for the Strategic Culture Foundation (SCF), Moscow.