The Japanese State Versus the People of Okinawa: Rolling Arrests and Prolonged and Punitive Detention

- Gavan McCormack, “Yamashiro Hiroji and the Okinawan Anti-Base Struggle”

- “Emergency Statement by 41 Criminal Law Scholars Demanding the Release of Yamashiro Hiroji,”

Yamashiro Hiroji and the Okinawan Anti-Base Struggle

Gavan McCormack

“If Takae and Henoko can be stopped, Japan will change. If they cannot be stopped then there is no future, either for Okinawa or for Japan.”1

Henoko, Takae, and Yamashiro Hiroji

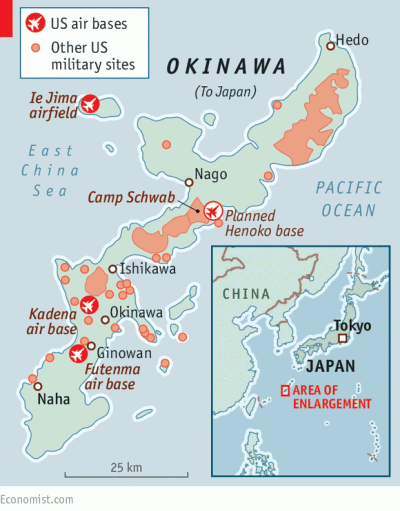

For anyone who has spent any time on the front lines of the protracted resistance struggle by the people of Okinawa against construction of new bases for the Marine Corps at Henoko and Takae, one indelible impression is likely to be the performances of the master choreographer of the resistance, Yamashiro Hiroji. Conducting the assembled citizens day after day, month after month, in song, dance, and debate, this retired (64 year old) public servant has seemed to be a natural leader of the struggle to delay or prevent construction of the projected new bases for the Marine Corps at Henoko, adjacent to the existing Camp Schwab base on Oura Bay, and in the “Northern Training Area” in the Yambaru forest at Takae.2 At Henoko, the resistance has managed to hold off the base construction so that major works initially planned in 1996 have yet to begin (although the state, following a Supreme Court judgment in its favour in December 2016, appears determined to start work in January 2017).

As for Takae, discussed below, the reversion to Japan of about half (4,000 hectares) of the huge Northern Training Area, a thickly forested zone in the north of the island used for jungle warfare training purposes, was promised in 1996, conditional on the government of Japan constructing for the Marines six “helipads” in the zone it was to retain to replace those in the zone being returned. Construction began in 2007, punctuated by clashes between strongly opposed villagers and police and construction officials. That struggle, discussed further below, blew up into major conflict in the latter part of 2016.

The Henoko struggle took more-or-less its present shape following the issue by then Governor Nakaima Hirokazu of a license permitting reclamation of much of Oura Bay, the projected base site and home of Japan’s and Okinawa’s most diverse and healthy coral, in December 2013 (counter to his repeated pledges of opposition to any such project and under extreme national government pressure). From July 2014, a large swathe of the bay was declared off-limits, markers for the proposed reclamation were laid out and concrete blocks dropped into its depths. In November, however, Nakaima was defeated by Onaga Takeshi, a conservative politician who nevertheless was committed to stopping Henoko construction “using every power at my command.” Once assuming office, Onaga set up a “Third Party” expert committee to advise him and, when in due course it confirmed that the Nakaima decision had indeed been legally flawed, in October 2015 he cancelled the license and ordered the works stopped. The national government promptly stepped in to rescind that order and the survey resumed. At the site, having exhausted every possible legal restraint without avail, citizens adopted non-violent direct action tactics, blocking and picketing the entrance to Camp Schwab Marine Corps base. Adjacent to the fishing village of Henoko, the struggle unwinding there became known as the Henoko struggle.

In February 2015, just before the opening of a mass protest meeting against the base construction, local Japanese security agents in the service of the US Marine Corps arrested three protesters at the gate of Camp Schwab. One was Yamashiro.3 He was held on suspicion of breaching the controversial and stringent “special criminal law,” adopted in 1952 at the height of the Korean War, which prescribed severe punishment for unauthorized entry or attempted entry into US bases in Japan. Since it had never been invoked in the 43 years since Okinawa “reverted” to Japan from the US in 1972, Yamashiro thus had the distinction of having being singled out for quite exceptional treatment. However, film footage of the event appeared to contradict the official account. He seems to have been actually ordering demonstrators to be especially careful not to cross the boundary line when he was suddenly attacked by Marine Corps security personnel, flung to the ground, handcuffed, and dragged feet-first into the base. Handed over to the Japanese police, he was held overnight and released the following day. As the Okinawa Times noted, it appeared to be a clear case in which the constitutional right to freedom of assembly, opinion, and expression had been sacrificed to the overarching extraterritorial rights enjoyed by the US.4

Over the next year, many others were subsequently detained for varying periods, but only one shared the distinction with Yamashiro of being detained under the special criminal law. That was the prefecture’s preeminent novelist and literary prize-winner, Medoruma Shun. Medoruma, while part of a flotilla of canoes and kayaks carrying the protest on behalf of the creatures of the Bay on a daily basis to the government (Coastguard) ships, was pulled from his kayak in Oura Bay on 1 April 2016, and held, first by US and then by Japanese authorities, for 34 hours. The implication of his detention under the special criminal law was that he had been planning to launch an attack on the base – from his kayak.5 It was plainly absurd. Like Yamashiro, he too was released without indictment.

If, however, laws were broken at Henoko and on Oura Bay, there is a prima facie case for thinking that the police and Coastguard were the guilty parties. Their mobilization to enforce a government construction project would appear to be in breach of the provisions of the Police Duties Execution Act and the Japan Coastguard Act, meaning that “both the police and the Japan Coastguard are consistently acting beyond their legal purviews and violating constitutional rights.”6

One can only speculate as to what the abortive invocation of the “special law” may have signified, but one explanation could be that the US side, irritated at the continuing delays in base construction, was thus pressuring Japan to exert more force to bring it back on schedule, while the Japanese side was reluctant to do that for fear of causing Okinawan anger to boil over, possibly threatening the entire base system.

During the complex events that followed Onaga’s cancelation of his predecessor’s reclamation license, law suits proliferated.7 Under a court ordered “amicable agreement” in March 2016, even preliminary survey works on Oura Bay were halted. They remained so till December 2016, when the Supreme Court ruled that Onaga had acted illegally. He then promptly cancelled his own order, though insisting that he would still stop base construction (by unspecified means). The state readied to start actual reclamation works from the New Year of 2017.

From Henoko to Takae

It was during that nine month lull in the Camp Schwab gate-front struggle that the focus shifted to the N-1 Gate in the Yambaru forest at Takae (access point to the Marine Corps Northern Training Area), about 40 kilometers away. There, the state concentrated on construction of a series of mini-bases for the Marine Corps’ Osprey VTOL aircraft, “Osprey pads” as they came to be known. As with so many aspects of the Okinawa base story, the term “helipad” was deliberately deceptive, implying something like a building top where a helicopter could take off and land whereas, as only gradually became clear, they were to be substantial structures, 75 metres in diameter and fed by specially constructed access roads that required clear-felling of wide swathes of forest and were designed to accommodate not helicopters but the distinctive Osprey (vertical take-off and landing powered aircraft) and Harrier jump-jet fighters. Though called “helipads” they were actually mini-bases. Two were completed and handed over to the Marine Corps in February 2015.

From July 2016, the state launched an intensive campaign to accelerate construction of the remaining four, determined to show President Obama that Japan was doing everything it could to maintain and reinforce the bilateral alliance (despite the delays and complications at Henoko). In place of the plan adopted in 2007 of building one Osprey-pad at a time so as to minimize damage to the forest it now moved to construct all four simultaneously. The estimated time for works completion was cut from 13 to 6 months, the daily number of trucks employed in delivering materials and equipment was quadrupled (33 to 124), many of them without license plates and therefore in breach of Okinawan road traffic law, SDF helicopters were mobilized (counter to the Self Defense law) to evade the civic blockade and deliver some very large equipment, and the number of trees felled rose to an estimated 24,000.8 To supervise the works, a massive police force was assembled, some 500 dispatched from mainland Japan, Police at the N-1 Gate site outnumbered citizens about 5 to 1.9

Like many others during this phase, Yamashiro shifted the focus of his protest from Henoko to Takae, from the defence of the sea creatures of Oura Bay to the defence of the denizens of the Yambaru forest. There, far from the public eye and scarcely noticed beyond Japan, a fierce battle raged between a massive police force and the tiny hamlet of Takae (population about 150 people) backed by Yamashiro and the citizen force, commonly a hundred or so, from around Okinawa and farther afield. It was a significant logistical challenge for the state to mobilize construction workers and materials to this relatively remote forest site, but it was much more so for Yamashiro and his citizen colleagues. They had to be able to mobilize their citizen forces at N-1 at all hours of the day and night, ready to face the overwhelming might of the state and knowing that they would inevitably be roughly dragged away, often to the accompaniment of abuse and insult.

Target Yamashiro, Takae, October-December 2016

At the height of this struggle, on 17 October 2016, Yamashiro was detained during a brief flurry at N-1 Gate. Ten weeks later, as the year ended, he was still in a detention cell at Nago Police Station.

Initially, the prosecutors sought an order for his detention for having been caught “red-handed” inflicting damage to property (cutting one or more strands of barbed wire to gain access to the Marine Corps zone known as the Northern Training Area. It had been widely reported that the state’s construction workers were chopping down trees by the thousands across a wide area of forest, with presumably serious effects on the flora and fauna. The only way for the citizens to confirm that was the way Yamashiro chose: cut the wire and go in to see. On the morning of 20 October, the summary court (kan-i saibansho) rejected the prosecutor’s argument. Later that day, prefectural police appealed to Naha District Court against that decision and re-arrested Yamashiro on different grounds (obstruction of officials performing public duty). The detention was allowed.

On the following morning, 21 October 2016, Yamashiro’s home and the tents of the protest movement at Takae were subjected to stringent searches, presumably on the supposition that Yamashiro had drawn up a detailed advance plan for the action. It appears that no materials were found. Yamashiro’s lawyer, Miyake Shunji, commented:

“It was improbable that any evidence would be found at Yamashiro’s home or at the tent of intent to do harm or interfere with prosecution of public duties, but clearly the intent was to oppress the opposition movement by increasing the number of arrests and widening the scope of investigation.”10

Target Yamashiro, Reviving Henoko Charges

On 11 November 2016, Yamashiro was indicted on both the wire-cutting and obstruction of public duties charges. His request for release on bail was rejected.

On 29 November 2016, Yamashiro was again arrested (for the third time since 17 October), along with three other activists, this time charged with “forcible obstruction of public business” at the Henoko site. Between 28 and 30 January, 2016 Yamashiro and others were alleged to have piled up 1,400 concrete blocks to try to obstruct entry to Camp Schwab base. Okinawan prefectural police again raided his home, the protest movement’s tents, and the office of the Okinawa Peace Movement Center:11 “Ten or more materials” (presumably boxes of material) were carted away, General Secretary Oshiro Satoru of the Okinawa Peace Movement Center commented:

“How could they possibly have expected to find materials relating to events almost a year earlier?12

On 20 December, two of the co-defendants were released. Along with one of the other defendants (who by this time was weak from twenty days of hunger strike) Yamashiro was re-arrested. The December indictments thus linked the earlier (Henoko) and later (Takae) phases of the resistance struggle. Yamashiro was the obvious central figure targeted by the authorities to crush the struggle in both its manifestations. At some high policy level in Tokyo, it seems that he had been chosen to serve as link between the two theatres of struggle. To justify the base construction cause, it would discredit him, showing him to be a violent fanatic, perhaps even a terrorist.

Detention

While many incidents of apparent use of excessive force by the riot police were reported in the Okinawan media, the struggle went for the most part unreported in Japan proper and globally. Occasionally tears were to be seen in the eyes of younger, Okinawan riot police as they dragged away, time and again, protesters old enough to be their parents, or even grand-parents, trying not to heed their pleas. Increasingly, riot police with no connection to the prefecture were sent in against the protesters for this reason.

While the citizens stood their ground against provocation by the police (mostly those brought in from Tokyo or Osaka), some Osaka prefectural police were recorded shouting abuse at the protesters as Dojinand Shinajin (natives or Chink/Chinese). It would seem hard to deny that this was hate speech, but deny it the government did.13 The dominant sentiment in Tokyo was that expressed by Prime Minister Abe who, opening the special session of the Diet in September 2016, conveyed special appreciation for the work being done by police and military personnel, drawing a standing ovation from the parliament.14 For Okinawans that applause was salt in their wounds.

By the end of 2016, Yamashiro had been held in virtual solitary confinement for about ten weeks, denied repeated requests for release and forbidden to have any visitors (including his family) other than his lawyer, periodically marched in and out of court-rooms shackled and hog-tied like a serial killer or a terrorist.15 Initially, he was refused the right to take delivery even of a pair of socks16 but, as protest over that began to spread, on 20 December that ruling was relaxed. He was forbidden long socks but allowed one pair of short ones, presumably adjudged to be unlikely to lend themselves to any suicide attempt.17Even that “concession,” however, was negated by the rule that he could not wear such socks when inside his cell.18

Despite it being well-known that Yamashiro suffers serious illness (for which he underwent prolonged hospitalization in 2015), the prefectural police and judicial authorities continue to prolong his detention by bringing fresh charges against him. Public policy might be called upon to justify extended detention in case the defendant is suspected of intent to commit violent acts or destroy evidence, or there are fears that he might flee, but such suspicions were absurd in the Yamashiro case.

Of the various charges now pending against him that of cutting a barbed wire fence or of trying to prevent public officials carrying out their duty were political rather than criminal acts. If Yamashiro did cut one or more strands of wire, that offence was far less serious than that of the state’s contractors in cutting thousands of trees in the Yambaru forest. As for the “shaking [of a contractor] by the shoulder causing bruising,” that would of course be serious if it had a premeditated character, but in the context of daily melees, first at the Camp Schwab Gate and then at the N-1 Gate, continuing over many months and in all weathers, and the overwhelming preponderance of force on the side of the state and its contractors, such premeditation seems improbable, while the number of protesters who have suffered bruising or other injury by being summarily grabbed, beaten, detained, thrown aside, in some cases leading to hospitalization, is not known but is certainly greater than one.19 On Oura Bay during 2014-5, protesting canoeists (including Medoruma) were commonly dragged from their boats, dunked in the sea, or carried miles away and dumped on remote shores without legal warrant by an organ supposedly entrusted with the defence of Japan’s shores and bays. The real violence was overwhelmingly committed by state police and military authorities.

Law, Citizenship, Protest

For the state, it seems that whatever it takes to accomplish the ends of base construction is legitimate. Although Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga insists that Japan is a law-governed state, a hochi kokka as he puts it,20 the evidence from Henoko and Takae suggests otherwise. There is no sign of appreciation of the fact that

“Overall, citizens’ activities to oppose the construction of a new base which are taking place around Camp Schwab [and the mini-bases at Takae] are part of the exercise of freedom of expression guaranteed by the constitution.” 21

Clearly of high priority, and presumably decided at some high policy level, is the removal of one of the central figures of the protracted non-violent resistance movement, Yamashiro. Once removed, he has to be shown to be wicked and conniving, and, if at all possible, violent. On that the state and its organs now work.

From December 2016, however, public attention to the Yamashiro case began to grow. A statement demanding his release was issued by an international group of scholars (including this author) on 16 December.22 A Japanese online petition calling for his release was issued a few days later.23 An American specialist on Japanese law, professor at Meiji University in Tokyo, Lawrence Repeta, published an article in the Japan Times, paying attention especially to Japan’s obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (notably Articles 9, 14, and 15.24 Inter alia, Repeta noted that “the only purpose served by Yamashiro’s repeated arrests and detention is to punish a man who has never been convicted of any crime.” The Covenant, he insists, “requires (sic) that Yamashiro be released pending trial.”

A group of (initially) 41 criminal law specialists published in the Okinawa media a statement highly critical of the authorities’ handling of the case. That statement, translated by Sandi Aritza for the Asia-Pacific Journal, follows.

Emergency Statement by Criminal Law Scholars Demanding the Release of Yamashiro Hiroji

Translated by Sandi Aritza

Press Release: December 28, 2016

The Japanese government boasts that Japan is a country that respects the rule of law while using state power to trample on the democratically expressed will of the Okinawan people. As people study and think about the law, we are overcome by a feeling of powerlessness. Very unfortunately, the criminal justice system follows in the government’s footsteps, and is attempting to use the criminal code to suppress a non-violent, peaceful protest movement. Making it a crime to protect peace was a characteristic of the legal framework governing public order during World War II. However, today, it may still be possible to reverse this trend and take back the law. Therefore, we found it necessary to explain, from the perspective of legal scholars, why the arrest and detention of Mr. Yamashiro are themselves unlawful, and why his indictment must be rescinded and he must be released.

Ten days ago, a group of foreign intellectuals released a statement titled “Demand for the Release of Yamashiro Hiroji and Others”, and subsequently, Okinawa’s two newspapers quoted Mr. Yamashiro, still in detention, as saying that “Okinawans must unite to overcome this painful predicament” and that “the future is ours.” We feel that as scholars of criminal law in Japan, we have to immediately respond to this situation in which the criminal justice system is meting out injustice, and we therefore announce the attached “Emergency Statement by Criminal Law Scholars Demanding the Release of Yamashiro Hiroji” (December 28, 2016).

Organizers: Kasuga Tsutomu (Kobe Gakuin University), Honjou Takeshi (Hitotsubashi University), Maeda Akira (Tokyo Zokei University), Morikawa Yasutaka (University of the Ryukyus)

The full list of the 41 signatories as of 1 p.m. on December 28 can be found in Japanese at http://maeda-akira.blogspot.jp/2016/12/blog-post_27.html.

A second batch of signatures will be collected until mid-January 2017.

Emergency Statement

Yamashiro Hiroji, 64, director of the Okinawa Peace Movement Center, has been in detention pending trial for more than 70 days. Mr. Yamashiro has been arrested and indicted three times. He has not been allowed visitors and has not been permitted to see his family. Mr. Yamashiro has been interviewed by the two local newspapers through his lawyer and has said that “the Onaga prefectural administration and all Okinawans are being placed in a painful predicament” and that “many of my friends have long engaged in action to prevent [the construction] with all their might, and I cannot suppress my overwhelming anger toward the political power and violence that has been used to forcefully repress them devastatingly and mercilessly” (Okinawa Times, December 22, 2016; Ryukyu Shimpo, December 24, 2016). Mr. Yamashiro’s lengthy detention constitutes confinement without probable cause (a violation of Article 34 of the constitution). He must be released immediately. The reasons are as follows.

- On October 17, 2016, on the grounds that while engaging in protest activity against the construction of helipads for Osprey training in the U.S. military’s Northern Training Area, Mr. Yamashiro cut one strand of barbed wire on top of a fence put up by Okinawa Defense Bureau employees to prevent entrance, and was arrested at the scene. On October 20, the Naha Summary Court dismissed the Naha district public prosecutors’ office’s petition for Mr. Yamashiro’s detainment, but the prosecutors’ office appealed and that same night, the Naha District Court ruled that Mr. Yamashiro should be detained.

- Prior to this, at around 4:00 p.m. on the same afternoon, the Okinawa prefectural police arrested Mr. Yamashiro again, serving him with an arrest warrant on the suspicion of obstructing an Okinawa Defense Bureau employee in the performance of his duties and inflicting bodily harm. On November 11, Mr. Yamashiro was indicted on the charges indicated in both (i) and (ii), and on November 12, his request for release on bail was denied. (His appeals, including an appeal of an order denying his access to visitors, were also denied.)

- Further, on November 29, Mr. Yamashiro was arrested again, this time on suspicion of forcible obstruction of business in relation to the construction of a new base in Henoko, Nago City, and on December 20, he was indicted on this charge.

Mr. Yamashiro is now being detained on the grounds that, because of the above three incidents, there is “probable cause to suspect that he has committed a crime” (suspicion of crime) and “probable cause to suspect that he may conceal or destroy evidence” (Code of Criminal Procedure, Article 60).

However, first, with regard to the suspicion that he has committed a crime, it is clear that the above three incidents concern acts performed as forms of political expression that convey the will of “All Okinawa,” a people’s movement that calls for abandonment of the plan to build a new base in Henoko and removal of the Osprey; there can only be “probable cause to suspect that a crime has been committed” with respect to the exercise of such a constitutional right in cases where the act violates a superior interest. Freedom of political expression must be protected to the greatest extent possible. There is a high likelihood that all of the incidents occurred accidentally and unavoidably during collisions with riot police members attempting to block protest activities, and in each case the extent of criminality is exceedingly low. In (i), the barbed wire that was cut was merely a single strand with a monetary value of approximately 2,000 yen. Regarding (ii), an Okinawa Defense Bureau employee reported injury on the grounds that he sustained a blow to the right arm when Mr. Yamashiro grabbed and shook him by the arm and shoulder. This is a de minimis case where voluntary questioning should have been sufficient. As for (iii), the incident occurred ten months ago—near the end of January, non-violent protesters, who were forcibly removed by the riot police when they sat on the road in front of the gate to Camp Schwab in order to prevent the entrance of construction vehicles, piled concrete blocks in front of the gate instead of sitting there, and the blocks were easily removed each time a vehicle was to enter the gate. In fact, the riot police were deployed and base construction work by the Okinawa Defense Bureau continued. In other words, Mr. Yamashiro’s actions did not warrant suspicion of criminality or physical detention.

Even if the suspicions against Mr. Yamashiro were hypothetically found to be valid, the dominant thinking in scholarship on the code of criminal procedure dictates that the risk of concealment or destruction of evidence as a reason for detention does not apply to cases where facts sufficient to prove a crime are apparent. Excluding case (ii), Mr. Yamashiro is unlikely to deny the facts of the charges against him. Further, Mr. Yamashiro is now being detained following indictment. The prosecutors have completed all investigation necessary for trial. Keeping a defendant in detention should be the very last resort used only when absolutely necessary to ensure the defendant’s presence in court. In the present case, it is inconceivable that there could be a risk of concealment or destruction of evidence of a crime. Therefore, there is no probable cause for Mr. Yamashiro’s detention.

Detention with no legal cause is unlawful. In addition, in a case where it cannot be expected that, if found guilty, the defendant will be subject to imprisonment, detention pending trial is never appropriate. Further, Mr. Yamashiro has health problems, and he is likely to suffer irreparable detriment if his physical confinement continues. In addition, his act that is suspected to be criminal was the exercise of a constitutional right, and detaining him has a chilling effect. Therefore, in light of the principle of proportionality, detaining Mr. Yamashiro for more than 70 days is unjustifiable. Given the above, keeping Mr. Yamashiro in detainment for any longer must be understood to constitute “unduly long detention” (Code of Criminal Procedure, Article 91).

In the context of the confrontation between Japan’s national government and Okinawa Prefecture over the U.S. military bases in Okinawa, Mr. Yamashiro’s lengthy detention is extremely worrisome. It suggests that Japan’s system of “hostage justice”, which has long been viewed as a problem, is now employed as a political tool. As scholars of criminal law, we cannot overlook this state of affairs. Mr. Yamashiro must be released immediately.

The Asia-Pacific Journal is grateful to the criminal law scholars for permission to translate and publish their Statement.

Notes

1 “Kankyo kaigi Okinawa taikai – ‘Kankyo-ken’ kakuritsu no giron o,” Okinawa taimusu, 24 October 2016.

2 Between 1982 and retirement in 2008, Yamashiro was an official in the Okinawan prefectural government, employed in various sections involving base workers, unexploded ordinance, and taxation.

3 “Henoko protesters detained by US military,” Ryukyu shimpo (English), 24 February 2016.

4 “’Keitokuho de futari taiho’ shinjigatai futo kosoku, naze,” editorial, Okinawa taimusu, 24 February 2016

5 Urashima Etsuko, “Medoruma Shun shi ga futo taiho,” Shukan kinyobi, 8 April 2016, pp. 7-8.

6 All Okinawa Council, et al., “Joint submission to United Nations, Human Rights Council, “Violation of freedoms of expression and peaceful assembly in Okinawa, Japan,” 11 December 2015, in Hideki Yoshikawa and Gavan McCormack, “Okinawa: NGO Appeal to the United Nations and to US military and government over base matters, December 2015 and December 2016,” The Asia-Pacific Journal – Japan Focus, December 2016.

7 On this complex process, see my ”Japan’s Problematic Prefecture – Okinawa and the US-Japan Relationship,” The Asia-Pacific Journal – Japan Focus, 1 September 2016.

8 Details in Okinawan media, July-August 2016, See especially “Takae doji chakko mubo na keikaku wa akiraka ni,” Okinawa taimusu, 28 August 2016,”Heripaddo koki tanshuku, Nichibei ryo seifu wa mori mo kowasu no ka,” Okinawa taimusu, 29 August 2016 and (24,000 trees felled) “Letter of concern and request, Inscription of Yambaru forest as a world natural heritage site,” 1 December 2016, in Yoshikawa and McCormack, op. cit.

9 To this author it was reminiscent of the “speedo” campaigns to complete construction of the Burma-Thailand railway in 1942. State policy (kokusaku) in both cases was unchallengeable, and whatever was necessary to accomplish it was deemed legitimate.

10 Watanabe Go, “Okinawa, han kichi undo rida Yamashiro gicho no koryu tsuzuku, ‘kyoken hatsudo’ no haikei wa?” Aera, 13 December 2016; See also, “Yamashiro gicho o saitaiho, komu shikko bogai, shogai yogi de,” Okinawa taimusu, 21 October 2016.

11 “4 Activists protesting US base relocation in Okinawa arrested,” Mainichi shimbun, 30 November 2016). Arrested with Yamashiro were Inaba Hiroshi, 66, from Ginoza together with Kinjo Takemasa, 59, and Kobun Sasaki, 40, both from Nago.

13 “Cabinet: No need for Tsuruho to apologize over ‘dojin’ issue,” Asahi shimbun, 22 November, 2016

14 “Abe’s instruction of Diet ovation for SDF criticized,” Japan Times, 27 September 2016.

15 The one exception to this was a prominent national politician and member of the House of Councillors, Fukushima Mizuho, who was allowed a brief interview on 20 December. (”Okinawa kunrenjo ‘henkan shikiten’ no kage de kogi rida horyu 2 kagetsu cho,” Chunichi Shimbun, 23 December 2016).

16 “‘Kutsushita no sashiire mitomete’ ‘pantsu to issho’ Okinawa kenkei ni 100 nin ga uttae,” Okinawa taimusu, 12 December 2016.

17 “Koryuchu no Yamashiro gicho e, kutsushita o sashiire jitsugen, Okinawa kenkei ga mitomeru,” Okinawa taimusu, 21 December 2016.

18 According to Fukushima, quoted in note 13, above.

19 For list of incidents of “Violence, Detention, and Arrests in Henoko, Okinawa in 2014-15,” see Yoshikawa and McCormack, op. cit.

20 “Kuni ‘hochi kokka’ de yusaburi,” editorial, Ryukyu shimpo, 25 October 2016

21 “Statement against wrongful detention in front of the Camp Schwab gate by riot police of Okinawa prefecture,” quoted in Yoshikawa and McCormack, op. cit.

22 “Okinawa, Nagosho de keisatsu de 50 nichi ijo mo koryu sarete iru Yamashiro Hiroji o shakuho seo”(We demand release of Yamashiro Hiroji and others from police detention!) see Okinawa taimusu and Ryukyu shimpo of 17 December, and see Peace Philosophy.

23 “Yamashiro Hiroji san ra no shakuho o,” (“Free Hiroji Yamashiro”)

24 Lawrence Repeta, “The silencing of an anti-US base protester in Okinawa,” Japan Times, 4 January 2017.