The Inaugural Speech of a US President: History, Wisdom and The Trump Presidency

Most of the pageantry involved in the inauguration of a president has nothing to do with the Constitution. All it actually says is that president is supposed to take the oath of office. Even the idea of swearing on a bible is just a custom, and the oath doesn’t include “so help me, God.”

George Washington decided to invoke God at the last minute. One president, Franklin Pierce, actually refused to swear on the “Good Book.”

So, technically Donald Trump could be sworn in on The Art of the Deal.

The inaugural speech is also just a custom. It started when Washington thought it might be a wise idea to say a few words. He wasn’t speaking to “the people,” by the way, he was talking to Congress. But giving a speech stuck as an idea, and eventually the show was taken outside – where for the next century most of the audience couldn’t hear a word the president was saying.

At least the world will get to hear and read Trump’s address. If only everyone had been allowed to vote.

One president died as a result of giving an address. It was 1841, and William Henry Harrison, who was 68, wanted to prove he was fit and gave his speech on a bitterly cold day without wearing an overcoat. The speech took more than two hours – the longest on record – and Harrison caught a cold. A month later he died of pneumonia.

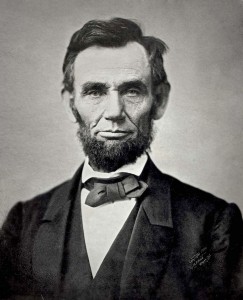

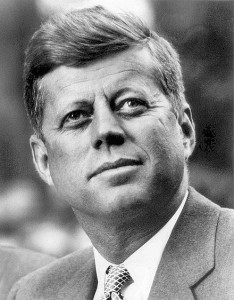

Aside from Lincoln (image left), Kennedy, and Garfield, most inaugural speeches haven’t been very memorable. At times they’ve been downers. In 1857, for example, James Buchanan attacked abolitionists for making a big deal about slavery. Ulysses Grant complained about being slandered. Warren Harding and others were simply boring.

Aside from Lincoln (image left), Kennedy, and Garfield, most inaugural speeches haven’t been very memorable. At times they’ve been downers. In 1857, for example, James Buchanan attacked abolitionists for making a big deal about slavery. Ulysses Grant complained about being slandered. Warren Harding and others were simply boring.

There have been some memorable lines. “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself,” said Franklin Roosevelt. Kennedy, with an assist from several others, came up with “Let us never negotiate out of fear, but let us never fear to negotiate.”

And let’s not forget George H.W. Bush, who compared freedom to a kite. Not a very high bar.

According to scholars who have analyzed the speeches, the form has evolved. In the old days, presidents talked quite a lot about the Constitution. Now we have more “rhetorical” presidencies, meaning that the chief executive bypasses the constitution – and congress – and appeals directly to the people. The problem, which was recognized by the founding fathers, is that this can lead to demagoguery – appeals to passion rather than reason. And since Nixon we’ve had several inaugurations with leaders who offer mainly platitudes, emotional appeals, partisan and anti-intellectual attacks and human interest stories rather than evidence, facts and rational arguments.

Since Nixon we’ve also had professional speechwriters, and an emphasis on getting as much applause as possible. Meanwhile, the reading level has dropped. The early speeches were written at the college level. Now they require only eighth grade comprehension.

We don’t hear much about the presidency of James Garfield, who was elected in 1880. One of the reasons was that he was shot after only four months in office, and died about two months later. But before he was inaugurated, he read over all the previous addresses to decide what to say. He found Lincoln’s speech to be the best. Who could beat this closing:

We don’t hear much about the presidency of James Garfield, who was elected in 1880. One of the reasons was that he was shot after only four months in office, and died about two months later. But before he was inaugurated, he read over all the previous addresses to decide what to say. He found Lincoln’s speech to be the best. Who could beat this closing:

We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

Partway through his own research, Garfield considered not giving a speech at all. But he pressed on, and boiled down the task to the following: first a brief introduction, followed by a summary of topics recently settled, then a section on what ought to be the focus of public attention, and finally, an appeal to stand by him in the independent and vigorous execution of the law. The speeches haven’t really changed much since then. Normally, they serve to reunite people after the election, express some shared values, present some new policies, and promise that the president will stick to the job description.

To put it mildly, Trump is expected to break with that formula.

In the end, Garfield’s speech didn’t match Lincoln’s. But it was eloquent and remains relevant today. He started with history, noting that before the US was formed the world didn’t believe “that the supreme authority of government could be safely entrusted to the guardianship of the people themselves.” Moving through the first century of US history, he concluded that after the Civil War people had finally “determined to leave behind them all those bitter controversies concerning things which have been irrevocably settled, and the further discussion of which can only stir up strife and delay the onward march.”

It was a case of wishful thinking. “The elevation of the negro race from slavery to the full rights of citizenship,” he continued, “is the most important political change we have known since the adoption of the constitution.” But the Black vote was still be suppressed, especially in the south. So he warned, “To violate the freedom and sanctity of the suffrage is more than an evil. It is a crime which, if persisted in, will destroy the government itself.”

A prescient warning as it turns out. With the installation of President Trump, the US faces serious threats to the freedom and sanctity of the right to vote, and other dangers that could ultimately destroy this system of government – secrecy, abuse of power, impunity, abandonment of the rule of law.

Garfield also made another point worth repeating: No religious organization, he noted, can be “permitted to usurp in the smallest degree the functions and powers of the National Government.” He was talking about the Mormon Church, which was exerting considerable influence out west at the time. But there are contemporary implications.

His concluding words about the end of slavery perhaps still resonate best. “We do not now differ in our judgment concerning the controversies of the past generations, and fifty years hence our children will not be divided on their opinions concerning our controversies,” he predicted. “We may hasten or we may retard, but we can not prevent, the final reconciliation. Is it not possible for us now to make a truce with time by anticipating and accepting its inevitable verdict?”

Apparently not yet.

“Enterprises of the highest importance to our moral and material well-being unite us and offer ample employment of our best powers,” said Garfield. “Let all our people leaving behind them the battlefields of dead issues, move forward, and in their strength of liberty and the restored Union, win the grander victories of peace.”