The Idiotic Economic Theory That’s Causing Governments to Blow Up Their Economies

No, We CAN’T Inflate Our Way Out of a Debt Trap

Top mainstream economists have pushed the theory that we can inflate our way out of a debt crisis.

Ben Bernanke and Paul Krugman said in 2009 that we should force inflation on the economy. University of Oregon economics professor Tim Duy said the U.S. will try to inflate its way out of debt.

Warren Buffet argued:

A country that continuously expands its debt as a percentage of GDP and raises much of the money abroad to finance that, at some point, it’s going to inflate its way out of the burden of that debt.

A top advisor to the French President said that the United States was “flooding the world with liquidity” to try to inflate away its debt.

This isn’t old news … it’s ongoing policy. Just last year, Paul Krugman praised Japanese leader Abe for trying to inflate away Japan’s debt:

Enter Mr. Abe, who has been pressuring the Bank of Japan into seeking higher inflation — in effect, helping to inflate away part of the government’s debt — and has also just announced a large new program of fiscal stimulus. How have the market gods responded?

The answer is, it’s all good. Market measures of expected inflation, which were negative not long ago — the market was expecting deflation to continue — have now moved well into positive territory. But government borrowing costs have hardly changed at all; given the prospect of moderate inflation, this means that Japan’s fiscal outlook has actually improved sharply. True, the foreign-exchange value of the yen has fallen considerably — but that’s actually very good news, and Japanese exporters are cheering.

In short, Mr. Abe has thumbed his nose at orthodoxy, with excellent results.

Sadly, the results aren’t so excellent for Japan. And quantitative easing – the mechanism with which central banks have tried to create inflation – could be backfiring.

Indeed, the whole idea that we can inflate our way out of debt trap is fatally flawed …

UBS economist Paul Donovan shows that governments can’t inflate their way out of debt traps:

The problem with the idea of governments inflating their way out of a debt burden is that it does not work. Absent episodes of hyper-inflation, it is a strategy that has never worked.

Megan McArdle points out:

It is a commonplace on the right that we’re going to have enormous inflation, not because Ben Bernanke will make an error in the timing of withdrawing liquidity, but because the government is going to try to print its way out of all this debt.

Joe Weisenthal notes that it doesn’t quite work this way:

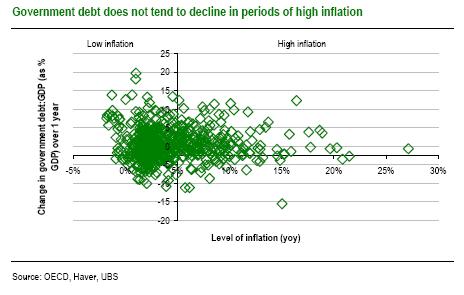

As this chart shows, instances of declining debt-to-GDP rarely coincide with periods of inflation. If it did If it did, we’d see more dots in the lower right-hand quadrant.

The bad news for central bankers is that creating currency isn’t like, say, diluting shareholders in a company. You’re always rolling your debt, and the market’s response to an inflationary strategy is (not surprisingly) higher interest rates. It’s a treadmill, and it’s extremely hard to get ahead.

Inflating your way out of debt works if you’re planning to run a pretty sizeable budget surplus–big enough that you won’t have to roll your debt over. Otherwise, your debt starts to march upward even faster, as old notes come due, and you have to roll them at ruinous interest rates. Hyperinflation might wipe out that debt, but also your tax base.

Financial Week notes:

Analysis shows even a sizable hike in CPI won’t do much for companies or households that owe money.Analysis released by Leverage World, a publication of debt research firm Garman Research, showed that companies that have issued debt at a coupon rate of 8%, as is typical for non-investment grade issuers, would have to see inflation hit 23% to inflate away the amount of debt they owe in 5.5 years. That’s the average amount of time that investors would have to hold such debt to compensate for the risk of default.

But investors would refuse to do so under such a scenario, Chris Garman, principal in the research firm, noted—not with yields on such debt currently running at 18%.

As Mr. Garman put it in the publication, inflation at that level “would crush the appeal of an 8% coupon.”

And while issuers would have to roll over their debt, they would find it impossible to do so. As he put it in an interview with Financial Week, “They’re staring down the barrel of an 18% coupon.”

Investment grade companies are in better shape. The same can’t be said for other public—or government—borrowers. Indeed, overall debt levels for the private and public sectors now run at roughly 3.5 times nominal GDP. That compares with 1.5 times from 1945 to 1980 and in the early 1920s.

To return to that level, Mr. Garman estimated that inflation would have to rise to around 12% or GDP increase by 75% over the next five years. Either scenario, he said, is hardly likely to materialize.

At a more realistic level of 3% real GDP growth and 2% inflation, Mr. Garman said, it would take 15 years before the overall U.S. debt level fell back under 1.7 times nominal GDP.

“There has been some talk of a rise in inflation as a panacea for distress and default,” he wrote in his report.

His analysis shows that such expectations vastly underestimate what’s required.

Economist Michael Hudson writes:

The United States cannot “inflate its way out of debt,” because this would collapse the dollar and end its dreams of global empire by forcing foreign countries to go their own way. There is too little manufacturing to make the economy more “competitive,” given its high housing costs, transportation, debt and tax overhead. The economy has hit a debt wall and is falling into Negative Equity, where it may remain for as far as the eye can see until there is a debt write-down…The Obama-Geithner plan to restart the Bubble Economy’s debt growth so as to inflate asset prices by enough to pay off the debt overhang out of new “capital gains” cannot possibly work. But that is the only trick these ponies know…

The global economy is falling into depression, and cannot recover until debts are written down.

Instead of taking steps to do this, the government is doing just the opposite. It is proposing to take bad debts onto the public-sector balance sheet, printing new Treasury bonds to give the banks – bonds whose interest charges will have to be paid by taxing labor and industry…

The economy may be dead by the time saner economic understanding penetrates the public consciousness.

In the mean time, bad private-sector debt will be shifted onto the government’s balance sheet. Interest and amortization currently owed to the banks will be replaced by obligations to the U.S. Treasury. It is paying off the gamblers and billionaires by supporting the value of bank loans, investments and derivative gambles, leaving the Treasury in debt. Taxes will be levied to make up the bad debts with which the government now is stuck. The “real” economy will pay Wall Street – and will be paying for decades.

Financial Times writer Wolfgang Münchau points out:

What I hear more and more, both from bankers and from economists, is that the only way to end our financial crisis is through inflation. Their argument is that high inflation would reduce the real level of debt, allowing indebted households and banks to deleverage faster and with less pain…

The advocates of such a strategy are not marginal and cranky academics. They include some of the most influential US economists…

The best outcome would be a simple double-dip recession. A two-year period of moderately high inflation might reduce the real value of debt by some 10 per cent. But there is also a downside. The benefit would be reduced, or possibly eliminated, by higher interest rates payable on loans, higher default rates and a further increase in bad debts. I would be very surprised if the balance of those factors were positive.

In any case, this is not the most likely scenario. A policy to raise inflation could, if successful, trigger serious problems in the bond markets. Inflation is a transfer of wealth from creditors to debtors – essentially from China to the US. A rise in US inflation could easily lead to a pull-out of global investors from US bond markets. This would almost certainly trigger a crash in the dollar’s real effective exchange rate, which in turn would add further inflationary pressure…

The central bank would eventually have to raise nominal rates aggressively to bring back stability. It would end up with the very opposite of what the advocates of a high inflation policy hope for. Real interest rates would not be significantly negative, but extremely positive…

Stimulating inflation is another dirty, quick-fix strategy, like so many of the bank rescue packages currently in operation … it would solve no problems and create new ones.

Mish Shedlock argues:

Inflationists make two mistakes when it comes to government debt. The first is in assuming government debt is more important than consumer debt. (It will be after consumer debt is defaulted away, but it’s not right now.) The second is that it’s not so easy to inflate government debt away either…Inflationists act as if unfunded liability costs and interest on the national debt stay constant. Also ignored is the loss of jobs and rising defaults that will occur while this “inflating away” takes place. Tax receipts will not rise enough to cover rising interest given a state of rampant overcapacity and global wage arbitrage.

Yet in spite of these obvious difficulties, the mantra is repeated day in and day out.

Inflating debt away only stands a chance in an environment where there is a sustainable ability and willingness of consumers and businesses to take on debt, asset prices rise, government spending is controlled, and interest on accumulated debt is not onerous. Those conditions are now severely lacking on every front.

CNN Money sounds a similar theme:

Some have suggested that the country could just “inflate its way” out of its fiscal ditch. The idea: Pursue policies that boost prices and wages and erode the value of the currency.

The United States would owe the same amount of actual dollars to its creditors — but the debt becomes easier to pay off because the dollar becomes less valuable.

That’s hardly a good plan, say a bevy of debt experts and economists.

“Many countries have tried this and they’ve all failed,” said Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Economy.com.

It’s true that inflation could reduce a small portion of U.S. debt. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that in advanced economies less than a quarter of the anticipated growth in the debt-to-GDP ratio would be reduced by inflation.

But the mother lode of the country’s looming debt burden would remain and the negative effects of inflation could create a whole new set of problems.

For starters, a lot of government spending is tied to inflation. So when inflation rises, so do government obligations, said Donald Marron, a former acting director of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), in testimony before the Senate Budget Committee.

“[W]e have an enormous number of spending programs, Social Security being the most obvious, that are indexed. If inflation goes up, there’s a one-for-one increase in our spending. And that’s also true in many of the payment rates in Medicare and other programs,” he said.

Inflation would also make future U.S. debt more expensive, because inflation tends to push up interest rates. And the Treasury will have to refinance $5 trillion worth of short-term debt between now and 2015.

“[The debt’s] value could go down for a couple of years because of surprise inflation. But then … the market’s going to charge you a premium interest rate and say ‘you fooled us once but this time we’re going to charge you a much higher rate on your three-year bonds,’” Marron said.

The Treasury is increasing the average term of its debt issuance so it can lock in rates for a longer time and reduce the risk of a sudden spike in borrowing costs. But moving that average higher won’t happen overnight. And, in any case, short-term debt will always be part of the mix.

Another potential concern: Treasury inflation-protected securities (TIPS), which have maturities of 5, 10 and 20 years. They make up less than 10% of U.S. debt outstanding currently, but the Government Accountability Office has recommended Treasury offer more TIPS as part of its strategy to lengthen the average maturity on U.S. debt.

The higher inflation goes, of course, the more the Treasury will owe on its TIPS.

Just last week, the CBO noted that interest paid on U.S. debt had risen 39% during the first five months of this fiscal year relative to the same period a year ago. “That increase is largely a result of adjustments for inflation to indexed securities, which were negative early last year,” according to the agency’s monthly budget review.

What’s more, the knock-on effects of inflation are not pretty. A recent report from the IMF outlined some of them: reduced economic growth, increased social and political stress and added strain on the poor — whose incomes aren’t likely to keep pace with the increase in food prices and other basics. That, in turn, could increase pressure on the government to provide aid — aid which would need to keep pace with inflation.

The Eurozone economist for Unicredit (Marco Valli) wrote a 27-page paper showing that we can’t inflate our way out of debt. The Economist summarizes:

the title is “Inflating away the debt overhang? Not an option”. Mr Valli argues that a central bank trying to achieve this aim would face three challenges

” 1. to create inflation in the current context of large economic slack and private/public sector deleveraging. 2 to do so in a way that faster inflation leads to negative real interest rates, thus generating a transfer from investors to the government and 3 to deliver negative real rates that are sufficiently large and/or last sufficiently long to allow for a significant reduction of the debt/GDP ratio”

Mr Valli argues that

“it is virtually impossible to satisfy these three conditions in a low-growth, high-public-deficit environment”

Retired economist Larry Macdonald notes:

Even if central banks abandon their inflation targets, it’s unlikely they can inflate the debt away. The U.S. bond market is so big that any signs of resurgent inflation will induce a wave of selling that would cause bond yields to spike upward and collapse the economy.

“We believe that any attempt to inflate away the massive [debt] would create a panic in debt markets,” wrote Peter Gibson in a report a while ago. Mr. Gibson is the former CIBC World Markets portfolio strategist who regularly won No. 1 rankings in the annual Brendan Wood analyst survey.

Jens Hilscher (Associate Professor of Finance at the International Business School and Department of Economics, Brandeis University), Alon Raviv (Lecturer in the International Business School, Brandeis University), and Ricardo Reis (Professor of Economics, Columbia University) say the data doesn’t support inflation as a cure for debt:

One way or another, budget constraints will always hold. This is true as much for a household or a firm as it is for the central bank or the government as a whole. If the US government is to pay its debt, then it must either raise fiscal surpluses or hope for higher economic growth; the former is painful and the latter is hard to depend on. It is therefore tempting to yield to the mystique of central banking and believe in a seemingly feasible and reliable alternative: expansionary monetary policy and higher inflation.Crunching through the numbers we find that this alternative is not really there.

If Inflation Won’t Solve the Debt Crisis … What Will?

If inflation won’t work, what will?

Do we need to impose more austerity on people to rein in the debt?

Nope … If we stopped throwing money at corporate welfare queens (including hundreds of billions a yearto the big banks), military and security boondoggles and pork, harmful quantitative easing, unnecessarynuclear subsidies, the failed war on drugs, and other wasted and counter-productive expenses, we could cut the debt without imposing austerity on the people.

Moreover, 140 years of economic history shows that – while excessive government debt is harmful – it is excessive private debt which causes depressions. But mainstream economists pretend that private debtdoesn’t even exist.

As we noted in 2012:

Neoclassical economists created the mega-banks, thinking that bigger was better. They pretend that it’s better to help the big banks than the people, debt doesn’t exist, high levels of leverage are good, artificially low interest rates are fine, bubbles are great, fraud should be covered up, and insolvent institutions propped up.

Indeed, even after a brief period of questioning their myths – after the 2008 economic crisis proved their core assumptions wrong – they have quickly regressed into their old ways.

Indeed, mainstream economics make so many illogical, unsupportable assumptions that it acts more like a cult than a science.

Postscript: Political terms like “sequestration” and the “fiscal cliff” are red herrings.