The Face of Australia’s Surveillance: Malcolm Turnbull’s Facial Recognition Database

Never miss an opportunity in the security business. A massacre in Las Vegas has sent its tremors through the establishments, and made its way across the Pacific into the corridors of Canberra and the Prime Minister’s office. Australia’s Malcolm Turnbull is very keen to make hay out of blood, and has suggested another broadening of the security state: the creation of a national facial recognition data base.

It stands to reason. Energy policy is in a state of free fall. The government’s broadband network policy has proven disastrous, uneven, inefficient and costly. Australia is falling back in the ranks, a point that Turnbull dismisses as “rubbish statistics” (importantly showing that President Donald Trump is not the only purveyor of fanciful figures).

The Turnbull government is also in the electoral doldrums, struggling to keep up with a Labor opposition which has shown signs of breaking away into a canter. The only thing keeping this government in scourers and saucepans is the prospect that Turnbull is the more popular choice of prime minister.

Enter, then, the prism of the national interest, the chances afforded to his political survival by the safety industrial complex. Turnbull, a figure who, when in the law, stressed the importance of various liberties, is attempting to convince all the governments of Australia that terrorism suspects can be detained for periods of up to 14 days without charge. Lazy law enforcement officials, rejoice.

Tagged to that agenda, one he wishes to run by the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) in Canberra, is the fanciful need for a national facial recognition database. This dystopian fantasy of an information heavy, centralised database is one Australians have historically have opposed with admirable scepticism. It has been something that Anglophone countries have tended to cast a disapproving look upon, a feature of a civilization suspicious of intrusions made by the executive.

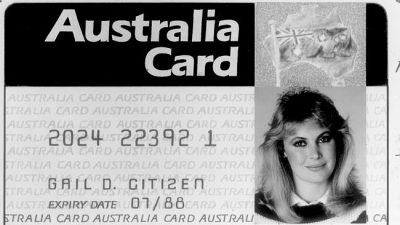

In the 1980s, the Australia Card was suggested as an administrative measure of convenience, but deemed by critics to be the first steps in the creation of a national surveillance system that would stretch, extend, and ultimately enlarge the powers of the state.

As law academic Graham Greenleaf would argue in 1987, the Australia Card Bill 1986 would “go beyond being a mere identification system, which the Government claims it is, and will establish the most powerful location system in Australia, and a prototype data surveillance system.”[1]

Had it been implemented, the card system would have applied to people of all ages, and, while not being compulsory, would have made it impossible, in Greenleaf’s sombre words, “for anyone to exist in Australian society without it”. Receipt of pay would not have been taxed at the required rate; receiving health insurance and social security payments would have been impossible.

Importantly, the bill was rejected twice in the Australian senate, generating the grounds for a move by the Hawke government to take Australia to the polls. It proved so unnerving to the senses of the public that the then prime minister quietly shelved it. The civil libertarians had won.

Times have darkened. In Australia, civil libertarianism is in quiet retreat, and the defenders of Big Brother chant with approval. Security and fear are garlanded and worshipped. Criticisms of the authoritarian bugbear are being treated with varying degrees of disdain and scorn.

Turnbull prefers to offer a chilling vision:

“Imagine the power of being able to identify, to be looking out for and identify a person suspected in being involved in terrorist activities walking into an airport, walking into a sporting stadium.”

It’s always good to imagine, to identify the citizen, to pretend that precision is the order of the day.

Concerns that this data base might be vulnerable to intrusive hacks and enterprising data pinchers is not a concern for the man in Canberra. This is the prime minister who presided over the creation of a data retention scheme on communications, a step deemed inimical in certain parts of the world to liberties (The European Court of Justice certainly thought so in 2016.)

“You can’t allow the risk of hacking to prevent you from doing everything to keep Australians safe”.

Safety is truly in the eye of the plodding beholder, and such a system risks entrenching a state of insecurity.

The operating rationale here is contempt for privacy, or that the Australian citizen could even care. That’s the nub of Turnbull’s argument: the state is abolishing an undervalued, near irrelevant concept for the sake of security.

“I don’t know if you’ve checked your Facebook page lately,” he chided journalists on Wednesday, “but people put an enormous amount of their own data up in the public domain.”[2]

Yet another dangerous authoritarian argument for the books.

Over three decades have passed since the failure of the Australia Card. But Turnbull won’t be concerned. The age of fear has been normalised, and those in the business of harnessing and marketing it see opportunities rather than concerns. As Channel Nine’s Sonia Kruger, co-host of the cerebrally light Today Show Extra exclaimed:

“I like it. I do. Bring it on. Big Brother, bring it on.”[3]

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He lectures at RMIT University, Melbourne. Email: [email protected]

Notes

Featured image is from North Coast Voices.