The European Power Elites

The Democratic deficit in Europe

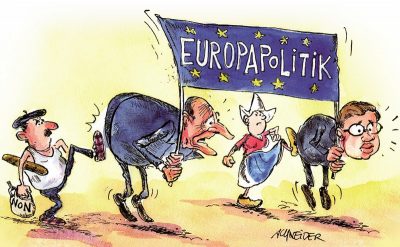

A wide debate is currently ongoing about the problem of democratic deficit in the European Union (Azman 2011), concerning the issue of political representation at the European level.

The problem is generally focused on two possible causes, one institutional and another socio-psychological: the institutional design of EU and the lacking of the social prerequisites of democratic rule at European level.

But it concerns more general questions about the nature and goals of the European integration (Majone 1998) and its configuration as an international organization of sovereign states or a federal state.

The current crisis is making the issue more and more crucial in the sense of an increasing strengthening of technocratic/functional authorities and a weakening of democratically accountable authorities (Cotta 2013).

A fundamental question arises from these premises:

Who really rules Europe?

The Commission, the Parliament, the Council of Ministers, the ECB, the corporate lobbying system, or a more general European Elite System?

The European elite system

The literature on the European elites highlights the presence of different approaches to this issue, generally mostly focused on specific aspects more then on its widest context.

A first perspective of studies is focused on the analysis of European political elite (Best, Lengyel & Verzichelli 2012), which results to have a complex configuration, strictly connected with the complex institutional design of the European polity, that is articulated in a set o institutions (Commission, Parliament, Council of Ministers, Council, European Central Bank and European Court of Justice) characterized by different levels of legitimacy, power and responsibility, independence and national or supranational anchorage.

From these studies results, furthermore, as the handling of the European crisis has strengthened institutions with a more supranational nature and predominant functional legitimacy (Commission and ECB) and weakened the institution with the more democratic legitimacy (the Council). Moreover, it increased the imbalance between regulatory policies and promotional policies and between technocratic/functional authorities and democratically accountable authorities (Cotta 2012).

Another set of studies deepened the analysis of the European governance from the perspective of policy networks (Peterson 2003) focusing the analysis of the nature of European policy making on the role played by hybrid arrangements of different actors (including private or nongovernmental institutions), with different interests in a given policy sector and the capacity to influence the policy success or failure.

The European Union represents a typical example of governance by policy network because of it highly differentiated polity system dominated by experts and highly dependent on government by committee.

A large number of studies has examined the lobbying activity of interests groups in the multi-level European governance structure (Richardson 2006). They show the emergence of an elite pluralist environment characterized by an ever more depoliticized institutional arrangements in the European institutions, the increasing in number of interests groups and the central role played by business associations, consultancy firms, think tanks and NGOs in the EU policy making.

Other studies focus on the rise of an European corporate elites (Heemskerk 2011), produced by the increasing strengthening of a network of transnational boards of interlocking directorate1 among the main European firms, also held together by the sharing of common norms. Furthermore, these studies emphasize the central political role played by the European Round Table of Industrialists (the most important meeting place for the European corporate elite) in the strengthening of the European governance as a mean to promote the development of a European economic space (Van Apeldoorn 2000).

The two approaches which treat the issue of European elites from a more integrated and systemic perspective are those based on the models of transnational power elites (Kauppi and Madsen 2013) and monetary power complex (Krysmanski 2007), which take into account all the different kinds of elites and their interconnections in the policy making.

The first puts the spotlight on the rise of new powerful social groups influencing the European policy making process (central bankers, commissioners, Euro-parliamentarians, diplomats, civil servants, lawyers and professionals of security) as part of a global restructuring of power related to the widest economic and political processes of globalization (Kauppi and Madsen 2013).

The second is focused on the analysis of the wealth concentration in Europe as a key factor in the understanding of the power dynamics. Krysmanski (2007, 2009) highlights the emergence of an increasing monetary power of organized and networked ultra-wealth, which is structured in four concentric groups composed by the super rich (the money elites), the corporate and financial elites, the political elites and the functional and knowledge elites.

*

Mario D’Andreta is a psychologist. He works as clinical and organizational psychologist and conducts independent research on the psychosocial dimensions of globalization and power. On his own blog, mariodandreta.net, he writes about psychosocial and socio-political issues concerned with social coexistence, local development, power elites, biopsychosocial wellbeing and acoustic ecology, aiming at promoting the development of a culture of pacific and creatively productive social coexistence. He can be contacted at [email protected].

Sources

Azman, K. D. (2011). The Problem of “Democratic Deficit” in the European Union, International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, Vol. 1 No. 5; May 2011

Best, H., Lengyel G. & Verzichelli L. (eds.) (2012). The Europe of Elites: A Study into the Europeanness of Europe’s Economic and Political Elites. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Cotta, M. (2012), Political Elites and a Polity in the Making. The Case of the EU, in Historical Social Research, vol. 37, pp. 167-192.

Cotta, M. (2013), Facing the crisis: the variable geometry of the European elite system and its effects, in J. Higley and H. Best eds. Political Elites in the Transatlantic Crisis, Houndmills, Palgrave

Domhoff. G. W. (2009) Who Rules America? Boston, Mass: McGraw-Hill

Heemskerk E.M. (2011). The social field of the European corporate elite: a network analysis of interlocking directorates among Europe’s largest corporate boards. Global networks, 11(4), 440-460

Kauppi, N. & Madsen, M.R. (Eds) (2013). Transnational Power Elites: The New Professional of Governance, Law and Security, London: Routledge

Krysmanski, H.J. (2007). Who will own the EU – the Superrich or the People of Europe?’, RLS policy paper 3/2007

Krysmanski, H.J. (2009). Elites and the monetary power comples. Paper given at the 7th Interdisciplinary Symposium on Knowledge and Space: “Knowledge and Power” Heidelberg, June 17-20, 2009, Department of Geography, U of Heidelberg, Klaus Tschira Foundation

Majone G. (1998). Europe’s ‘democratic deficit’: the question of standards, European Law Journal, Vol. 4, N. 1, 1998, pp. 5-28

Peterson, J. (2003). Policy Networks, Political Science Series

Richardson, J. (2006). Policy-making in the EU: interests, ideas and garbage cans of primeval soup, in Richardson J. (ed.), The European Union: Power and Policy-Making, Oxford University Press.

Van Apeldoorn B. (2000). Transnational class agency and European governance: The case of the European round table of industrialists. New Political Economy, 5(2), 157-181.

Note

1 “the linkages among corporations created by individuals who sit on two or more corporate boards” (Domhoff 2009)

Featured image is from Worldview.