The Division of the Korean Peninsula: In the Face of American Amnesia, The Grim Truths of No Gun Ri Find a Home

On the 70th anniversary of the division of the Korean peninsula, the Korea Policy Institute, in collaboration with The Asia-Pacific Journal, is pleased to publish a special series, “The 70th Anniversary of the U.S. Division of the Korean Peninsula: A People’s History.” Multi-sited in geographic range, this series calls attention to the far-reaching repercussions and ongoing legacies of the fateful 1945 American decision, in the immediate wake of U.S. atomic bombings of Japan and with no Korean consultation, to divide Korea in two. Through scholarly essays, policy articles, interviews, journalistic investigation, survivor testimony, and creative performance, this series explores the human costs and ground-level realities of the division of Korea. In Part 1 of the series Hyun Lee interviews Shin Eun-mi on The Erosion of Democracy in South Korea.

The truths of No Gun Ri have taken root in the heart of South Korea. A memorial tower, museum and garden of mournful sculptures have risen from the soil of the central valley where the 1950 refugee massacre took place. In the United States, however, home of the agents of those killings, much of the truth remains buried, by official intent and unofficial indifference.

Built by the South Korean government at a cost of $17 million, the new No Gun Ri Peace Park, covering 33 acres in Yongdong County, 100 miles southeast of Seoul, offers a straightforward account of what happened over four July days early in the Korean War:

As the North Korean army advanced into South Korea, residents of two Yongdong County villages were ordered from their homes by American troops, to be evacuated southward. Resting on railroad tracks near No Gun Ri, they were suddenly attacked by U.S. warplanes and many were killed. Over the next three days, U.S. troops killed many more as they huddled, trapped, under the No Gun Ri railroad bridge. An estimated 250 to 300 died.1

|

The No Gun Ri Peace Park, with its memorial tower on the left, museum in the center and education (conference) building at the upper right. The railroad bridge massacre site is out of the frame on the lower left. (Photo: Charles J. Hanley) |

In the 15 years since the world first learned of this mass killing, it has become increasingly clear that the U.S. Army’s 1999-2001 investigation of No Gun Ri suppressed vital documents and testimony, as it strove to exonerate itself of culpability and liability, and to declare – with an inexplicable choice of words – that the four-day bloodbath was “not deliberate.”2

But these suppressed archival documents, showing U.S. commanders ordering troops to fire on civilians out of fear of enemy infiltrators, are now on display at the peace park’s museum, illustrating a growing divide in how No Gun Ri will be remembered – or not – on two sides of the Pacific.

The official U.S. version “has framed the No Gun Ri story as an anecdotal war tragedy that can be allowed to fall into the domain of forgetfulness,” Suhi Choi writes in Embattled Memories, her newly published study of how the Korean War is memorialized.3

This article will describe some of the glaring irregularities of the official U.S. version, and show how the No Gun Ri park may prove a final bastion for securing the truth against that “domain of forgetfulness.”

The Deadly Orders of 1950

In the early weeks after North Korea’s invasion of the south on June 25, 1950, the fear that North Korean infiltrators lurked among southern refugees was fed by a few plausible reports and a torrent of rumors. Research at the U.S. National Archives by the Associated Press team that confirmed the No Gun Ri Massacre, both before and after their September 29, 1999 investigative report, found at least 16 documents in which high-ranking U.S. officers ordered or authorized the shooting of refugees in the war’s early months. Such communications, showing a command readiness to kill civilians indiscriminately, pointed to a high likelihood that the No Gun Ri killings, carried out by the 7th Cavalry Regiment, were ordered or authorized by a chain of command. A half-century later, lest that case be made, Army investigators excluded 14 of those documents from their report and misrepresented two others.4

In addition, the unit document that would have contained orders dealing with the No Gun Ri refugees, the 7th Cavalry journal for July 1950, is missing without explanation from the National Archives. The Army inquiry’s 2001 report concealed this fact, while claiming its investigators had reviewed all relevant documents and that no orders to shoot were issued at No Gun Ri.5

Here is how the Army report of 2001 dealt with three important pieces of evidence, among many documents suppressed or distorted:6

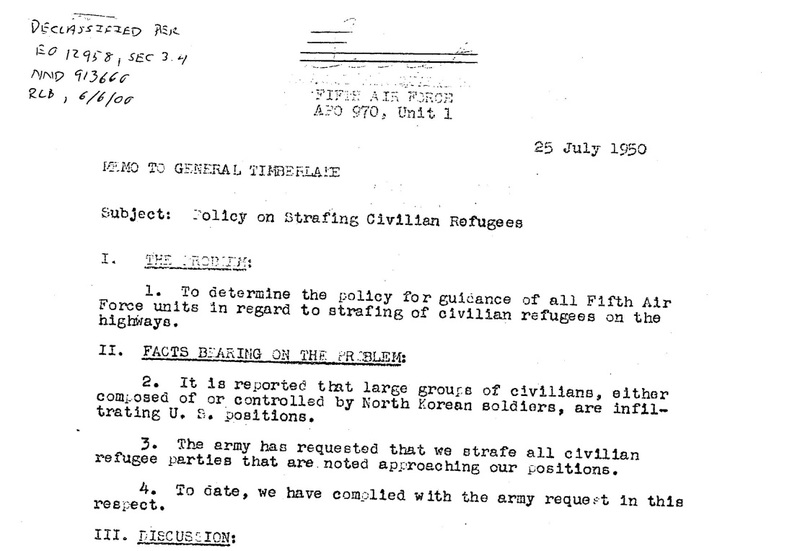

The Rogers Memo

Classified “Secret” and dated July 25, 1950, the day before the No Gun Ri killings began, the below memo was written by the U.S. Air Force’s operations chief in Korea, Colonel Turner C. Rogers, and sent to its acting commander, General Edward Timberlake. It got immediately to the point in its heading: “Subject: Policy on Strafing Civilian Refugees.”

Rogers wrote that “the Army has requested that we strafe all civilian refugee parties that are noted approaching our positions. To date, we have complied with the Army request in this respect.” He took note of reports that enemy soldiers were infiltrating behind U.S. lines via refugee columns, but said the strafings “may cause embarrassment to the U.S. Air Force and to the U.S. government.” He wondered why the Army was not checking refugees “or shooting them as they come through if they desire such action.” Rogers recommended that Air Force planes stop attacking refugees. Nothing has been found in the record indicating the memo had any effect, and the No Gun Ri slaughter the next day began with just such an air attack.

Pentagon investigators a half-century later couldn’t suppress this document, as they did many others, because it had been reported by the news media in June 2000, having been leaked to CBS News, possibly by Air Force researchers. Instead, the Army team, which did not reproduce the document in its report, chose to ignore the memo’s most important element, by not divulging that Rogers said the Air Force was, indeed, strafing refugees, in compliance with an Army request. Eliding that telltale paragraph No. 4, the Army investigators declared, “The Rogers memorandum actually recommends that civilians not be attacked unless they are definitely known to be North Korean soldiers.” For the sake of consistency in this particular deception, the investigative report went on to say that Rogers argued that the refugees were an Army problem and so the Army should be screening them, but it omitted Rogers’ clause, “or shooting them … if they desire such action.”7

In this way, the report that stands as the official U.S. record of a supposedly legitimate investigation disposed of one highly incriminating document.

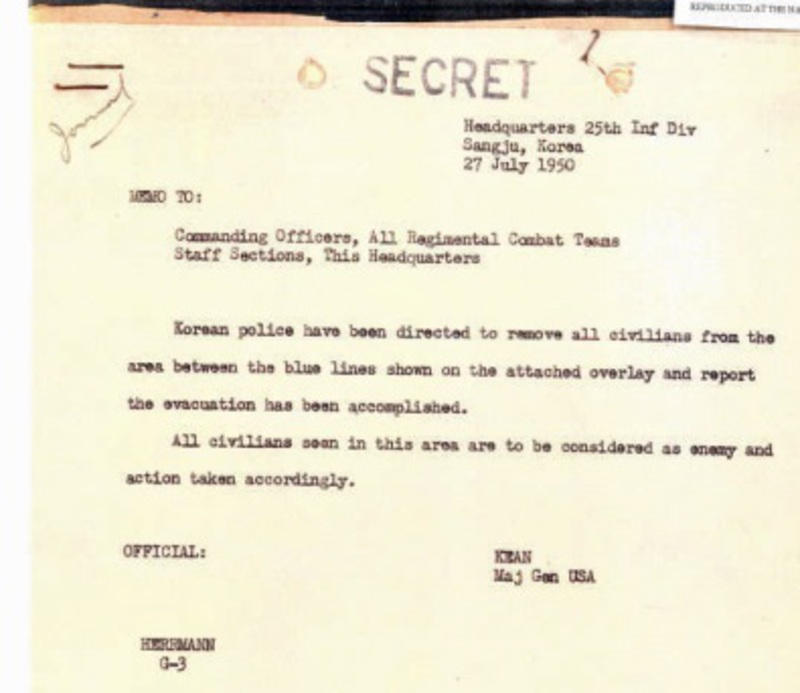

General Kean’s Order

Major General William B. Kean, commander of the 25th Infantry Division, which held the front line to the right of the 1st Cavalry Division, the division responsible for No Gun Ri, issued an order to all his units dated July 27, 1950, saying civilians were to have been evacuated from the war zone and therefore “all civilians seen in this area are to be considered as enemy and action taken accordingly.”

Again, the Army investigators of 2001 had to grapple with this explosive document, since it had been reported in the original AP story on No Gun Ri. And so they simply chose to write of this order, “There is nothing to suggest any summary measures were considered against refugees.”8 They suggested that when Kean said civilians should be treated as enemy, he meant front-line combat troops should “arrest” this supposed enemy, not shoot him—an implausible scenario in the midst of a shooting war.

To posit this unreal notion, the Army investigators had to conceal another division

headquarters document that said flatly that Kean’s order meant “civilians moving around in combat zone will be considered as unfriendly and shot.”9Other, similar communications were relayed across the division area, including one in which Kean “repeated” instructions that civilians were considered enemy and “drastic action” should be taken to prevent their movement.10 These, too, were suppressed by the Army investigators of 2001.

The Muccio Letter

Perhaps the most important document excluded from the U.S. Army’s 300-page No Gun Ri Review was a U.S. Embassy communication with Washington that sat unnoticed for decades at the National Archives. In 2005, American historian Sahr Conway-Lanz reported his discovery of this document, a letter from the U.S. ambassador to South Korea in 1950, John J. Muccio, to Dean Rusk, then-assistant secretary of state for Far Eastern affairs, dated July 26, 1950, the day the killings began at No Gun Ri.11 In it, Muccio reported to Rusk on a meeting that took place the previous evening among American and South Korean officials, military and civilian, to formulate a plan for handling refugees.

He wrote that the South Korean refugee problem “has developed aspects of a serious and even critical military nature.” Disguised North Korean soldiers had been infiltrating American lines via refugee columns, he said, and “naturally, the Army is determined to end this threat.” At the meeting, he wrote, “the following decisions were made: 1. Leaflet drops will be made north of U.S. lines warning the people not to proceed south, that they risk being fired upon if they do so. If refugees do appear from north of U.S. lines they will receive warning shots, and if they then persist in advancing they will be shot.” The ambassador said he was writing Rusk “in view of the possibility of repercussions in the United States” from such deadly U.S. tactics.

The letter stands as a clear statement of a theater-wide U.S. policy to open fire on approaching refugees. It also shows this policy was known to upper ranks of the U.S. government in Washington.

In 2006, under pressure for an explanation from the South Korean government, the Army acknowledged that its investigators of 1999-2001 had seen the Muccio letter, but it claimed they dismissed it as unimportant because it “outlined a proposed policy,” not an approved one – an argument that defied the plain English of the letter, which said the policy of shooting approaching refugees was among “decisions made.”12 In his book Collateral Damage (2006), Conway-Lanz attests to the letter’s crucial importance, writing that “with this additional piece of evidence, the Pentagon report’s interpretation (of No Gun Ri) becomes difficult to sustain” – that is, its conclusion that the refugee killings were “not deliberate” became ever more untenable.13

Washington’s sensitivity on the Muccio letter is seen in a 2006 cable sent by then-Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice to the U.S. Embassy in Seoul, found in the Wikileaks dump of State Department cables. Rice suggested the South Koreans would not get an explanation in writing of the handling of the Muccio letter, as requested.14 Presumably that would enable further obfuscation as necessary.

In Embattled Memories, Choi notes that the Muccio letter “proved that the U.S. military had a policy of shooting approaching refugees during the Korean War. Nonetheless, this counter-voice did not last long in the U.S. media. The evidence of the No Gun Ri story quickly melted into the amnesia that is the American collective memory of the Korean War.”15

The Army’s conscious “amnesia” extended to more than a dozen other archival documents from the Korean War’s first months in which commanders, for example, ordered troops to “shoot all refugees coming across river,” ordered “all refugees to be fired on,” and declared refugees to be “fair game.”16 The Army researchers who found them highlighted such incriminating passages, but they were excluded from the Army report. The report also suppressed damning testimony from veterans of the mid-1950 warfront, who confirmed civilians were being killed indiscriminately. “It had been passed around that if you saw any Korean civilians in an area you were to shoot first and ask questions later,” one testified.17 “In that war we shoot [sic] everybody that wore white,” said another, white being the everyday garb of rural Koreans.18 “The word I heard was ‘Kill everybody from 6 to 60,’” testified a third.19

The suppressed documents were later found in the Army investigation’s own processed files at the National Archives; the ex-soldiers’ transcripts were obtained via Freedom of Information Act requests.

In Defense of the Truth

Although the truth of mid-1950 South Korea and No Gun Ri was whitewashed and distorted at every turn in 2001 in Washington, DC, it has now found a home in the two-story, 20,365-square-foot memorial museum and its surrounding three-year-old No Gun Ri Peace Park, a gently landscaped place of arched bridges and flowered walkways, stretching from the bullet-pocked railroad underpasses of 1950, through a garden of powerfully evocative sculptures bearing such titles as “Ordeal” and “Searching for Hope,” to the bottom of a path leading to a hilltop cemetery and the graves of No Gun Ri victims, marked “1950-7-26.”

The No Gun Ri railroad bridge, site of the 1950 refugee massacre. (Photo: Charles J. Hanley) |

Visitors (an estimated 120,000 came in 2014) will find the warning words of Ambassador Muccio and Colonel Rogers behind the museum’s glass display cases, along with numerous “shoot refugees” orders. A diorama depicts the unfolding events of late July 1950. One wall bears the names of No Gun Ri’s dead. The truths of No Gun Ri can be found as well in nearby towns and villages, home of survivors who have testified to what happened, of a man whose face was shredded by bullets as a boy at No Gun Ri, a woman whose eye was blown out, others living with the legacy of livid scars, dents in their flesh and in their psyches. Elsewhere in South Korea, others have also worked to embed No Gun Ri in the national memory, producing a major studio’s feature film, a superbly drawn, two-volume graphic narrative, and an award-winning three-part television documentary.20

The park should become “a place where everyone can feel and learn the lessons of history,” South Korea’s security minister, Jeong Jong-seop, told a gathering last September of international peace museum directors at the park’s conference

building. Park director Chung Koo-do told the same gathering that No Gun Ri is “a historical issue that both Korean and American citizens should remember.”21

No Gun Ri Peace Park memorial tower (Photo: Charles J. Hanley) No Gun Ri Peace Park memorial tower (Photo: Charles J. Hanley) |

But the memory divide—East and West—can only grow. In the United States, the Korean feature film, A Small Pond, found no distributor. The graphic narrative, though translated into French and Italian, has not been published in English. Kill ‘Em All, a hard-hitting BBC documentary on No Gun Ri, aired in Britain in prime time yet was shunned in America.22 Two years after the Army’s deceitful report, a Pentagon-affiliated publisher issued an Army apologist’s polemic on No Gun Ri, an often-incoherent book packed with disinformation.23 In the English-language Wikipedia, the “No Gun Ri Massacre” article became a Wikipedic free-for-all between jingoistic denialists and the truth. Finally, ironically around the time the Korean park was opened in 2011, the U.S. Defense Department purged from its website the Army’s investigative report, further pushing No Gun Ri toward official oblivion.

Refugee tableau at the No Gun Ri Peace Park (Photo: Charles J. Hanley) |

That 2001 report, with its self-evident gaps and often clumsy deceptions, will remain on display at the No Gun Ri museum, as the memorial park grows into its role as final defender of the grim and unchallengeable realities of No Gun Ri. The realities extend beyond No Gun Ri: In 2005-2010, in good part because of the No Gun Ri revelations, South Koreans filed reports with their government’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission on more than 200 other alleged mass killings by the U.S. military in 1950-51, most said to be indiscriminate air attacks.24 The U.S. government has shown no interest in investigating those allegations.25

Charles J. Hanley is a retired Associated Press correspondent who was a member of the Pulitzer Prize-winning AP reporting team that confirmed the No Gun Ri Massacre in 1999. He is co-author of The Bridge at No Gun Ri (Henry Holt and Company, 2001).

The original 1999 Associated Press interactive Web package on No Gun Ri

Three 2008 Associated Press articles on the work of South Korea’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission:

On the U.S. role in mass executions

On the U.S. military’s indiscriminate killing of civilians

Recommended citation: Charles Hanley, “In the Face of American Amnesia, The Grim Truths of No Gun Ri Find a Home”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 9, No. 3, March 9, 2015.

Notes

1 Information about the No Gun Ri Peace Park was obtained during a visit by author in September 2014.

2 Charles Hanley, “No Gun Ri: Official Narrative and Inconvenient Truths.” Critical Asian Studies 42:4 (2010): 589–622; also in Truth and Reconciliation in South Korea: Between the Present and the Future of the Korean Wars, ed. Jae-Jung Suh (London and New York: Routledge 2013),68–94.

3 Suhi Choi, Embattled Memories: Contested Meanings in Korean War Memorials (Reno: University of Nevada 2014), 17.

4 See Charles J. Hanley, Sang-Hun Choe, Martha Mendoza, The Bridge at No Gun Ri (New York: Henry Holt.2001), 286. See also Hanley, Critical Asian Studies, 609.

5 See Hanley, “No Gun Ri: Official Narrative and Inconvenient Truths,” 607.

6 The U.S. Army investigation’s handling of these three documents is detailed in Hanley, Critical Asian Studies, 599-609.

7 Office of the Inspector General, Department of the Army, No Gun Ri Review (Washington, D.C. January 2001), xi, 98.

8 Office of the Inspector General, Department of the Army, No Gun Ri Review, xiii.

9 Hanley, “No Gun Ri: Official Narrative and Inconvenient Truths,” 609.

10 Ibid.

11 Sahr Conway-Lanz, “Beyond No Gun Ri: Refugees and the United States Military in the Korean War”. Diplomatic History 29:1 (2005): 49-81.

12 “US Still Says South Korea Killings ‘Accident’ Despite Declassified Letter,” Yonhap News Agency, 30 Oct. 2006; Hanley and Mendoza, “1950 ‘Shoot Refugees’ Letter Was Known to No Gun Ri Inquiry, but Went Undisclosed,” The Associated Press, 14 April 2007.

13 Conway-Lanz, Collateral Damage: Americans, Noncombatant Immunity, and Atrocity after World War II (New York: Routledge 2006), 99.

14 U.S. State Department cable. 31 August 2006. “Response to Demarche: Muccio Letter and Nogun-ri.” From Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice to U.S. Embassy, Seoul.

15 See Choi 11.

16 Hanley, “No Gun Ri: Official Narrative and Inconvenient Truths,” 609-610.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

20 Namely, writer-director Lee Saang-woo’s film A Little Pond; the graphic narrative No Gun Ri Story, by Park Kun-woong and Chung Eun-yong; Munwha Broadcasting Corp.’s series “No Gun Ri Still Lives On.”

21 “Welcome Address,” “Tragic Memories of the No Gun Ri Victims’ Community,” Report of the 8th International Conference of Museums for Peace, Sept. 19-22, 2014, The No Gun Ri International Peace Foundation.

22 British Broadcasting Corp., Kill ‘em All, Timewatch, 1 Feb. 2002.

23 Robert L. Bateman, No Gun Ri: A Military History of the Korean War Incident (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2002)

24 John Tirman, The Deaths of Others: The Fate of Civilians in America’s Wars (New York: Oxford.2011).

25 Hanley and Hyung-Jin Kim, “Korea Bloodbath Probe Ends; US Escapes Much Blame.” The Associated Press (Seoul), 11 July 2010.