The Diary of Lena Mukhina: An Important Document on the Leningrad Blockade (1941-1944) by Germany’s Wehrmacht

Lenas Tagebuch, translated by Lena Gorelik and Gero Fedtke, Munich, 2013

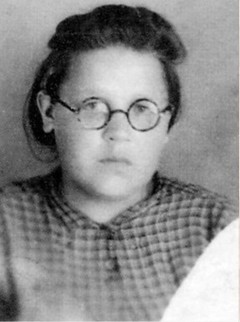

A year ago, the Munich-based Graf company published the diary of Lena Mukhina in German. Mukhina had witnessed as a student the first year of the German Wehrmacht’s blockade of Leningrad. Her diary was discovered in archives by Russian historians only a few years ago and was first published in Russian in 2011.

The diary is an important historical document relating to one of the greatest, although often forgotten, war crimes of German imperialism. About 1.1 million people lost their lives during the Nazis’ blockade of Leningrad between late summer 1941 and early 1944. It was one of the longest sieges of a city in world history.

More than a million Red Army soldiers died in the defence of Leningrad and another 2.4 million were wounded. Some 130,000 soldiers died on the German side, while 480,000 were wounded and 220,000 disappeared or were captured.

Lena’s diary begins in May 1941 and ends in late May 1942, when she was evacuated from Leningrad. At the beginning of the diary, the reader is introduced to an introverted, 16-year-old girl. Lena lives with her aunt Lena and Aka, a family friend, in a communal apartment in Leningrad. The family is poor and survives mainly by borrowing money. Lena has few friends at school and is unhappily in love with Vova, a boy in her class. Despite her efforts to be a “good Soviet schoolgirl,” her grades are not very good.

The tone of the diary changes abruptly on June 22, 1941, when the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union. Like millions of other Soviet citizens, she hears the speech of Foreign Minister Molotov on the radio. Stalin, shocked by the Nazi invasion he had failed to anticipate despite numerous warnings, would not make a statement until two weeks after the outbreak of war.

Nurses assisting the wounded during the first bombardment

Nurses assisting the wounded during the first bombardment

On June 23, Lena notes that the population is unprepared for war. She writes:

“To tell the truth, neither we nor any of the people in our block of flats are ready to deal with an attack: We don’t know where to find a medical aid centre, a decontamination site, an air-raid shelter; we don’t know where there are any air defence units or how we are supposed to react to bombing raids and firebombing.” [p. 53]

Only a few weeks before the war began, Lena had recorded her thoughts about Soviet military exercises in her diary: “Day

after day, soldiers are training with their commanders, and when the enemy attacks us—and that’s bound to happen, sooner or later there’ll be war—we can be absolutely sure of victory. We know what we’ll be defending, how we’ll be defending it and who we’ll be defending.” [p. 42]

In fact, the Soviet Union was far from being militarily prepared for the attack. Much of the leadership of the Red Army had been exterminated in the Great Terror of 1937. Most of the victims had been trained and educated under the leadership of Leon Trotsky, who led the Red Army from 1919 to 1924. Stalin decimated the country’s military leadership–much to Hitler’s delight.

Hitler’s assumption of power in January 1933 was a result of the false policies of the Stalinist bureaucracy. The ultra-left course it imposed on the German Communist Party prevented a united struggle of the German working class against the Nazis and made Hitler’s victory possible.

In the months that followed, the Stalinist bureaucracy swung to the right and adopted the disastrous strategy of the “Popular Front.” A struggle for socialism via the revolutionary mobilisation of the working class was explicitly rejected. Instead, workers in Spain and France were to limit themselves to supporting bourgeois democracy against fascism.

The result was further devastating defeats. At the same time, tens of thousands of Trotskyists and hundreds of thousands of other socialist workers and intellectuals were murdered in the Soviet Union.

In 1939, Stalin entered upon a pact with Hitler, believing it would prevent a German attack on the Soviet Union. In reality, the pact paved the way for the German invasion of Poland a week later.

While Leon Trotsky laboured incessantly in exile to warn of a Nazi attack on the Soviet Union, the Stalinist bureaucracy was set on lulling the population into a false sense of security.

For Lena, as for millions of workers, intellectuals and peasants, the attack on the Soviet Union came as a shock. The Red Army was forced into retreat in the first months of the war. By the end of the year, the Wehrmacht had reached the outskirts of Moscow. The Soviet army and people were deeply demoralised. Confidence in the Soviet government, as far as it still existed after the bloody terror of the 1930s, was shattered.

After the Red Army was forced to surrender the Ukrainian capital of Kiev—some 500,000 Red Army soldiers had lost their lives defending the city—Mukhina wrote on September 22:

“I am still alive and able to write in my diary. I’m no longer convinced at all that Leningrad won’t be abandoned. So much has been said, we’ve heard so many fine words and speeches: Kiev and Leningrad are impregnable fortresses!!!… Never will a fascist set foot in the flourishing capital of the Ukraine, never will he be able to enter our country’s northern pearl, Leningrad. But today it was reported on the radio … after several days of bitter fighting our army … withdrew from Kiev! What does this mean? No one can understand it.” [pp. 115-16]

The Volkovo cemetery

The Volkovo cemetery

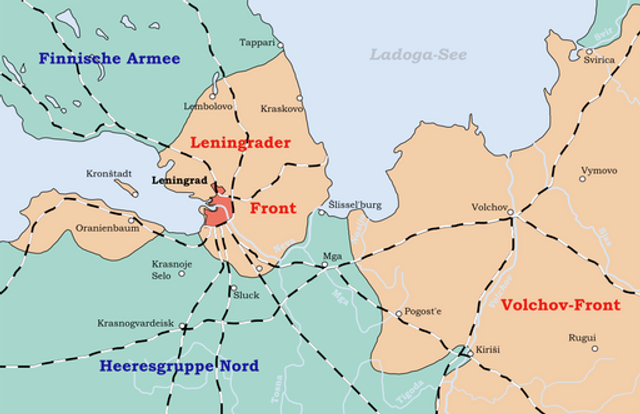

Already by the autumn of 1941 Leningrad was virtually encircled. Only Lake Ladoga had not been cut off by the Nazis and continued to provide a connection to the outside world. In September, air attacks began with both conventional and incendiary bombs, which led to approximately 50,000 casualties by the end of the war—16,474 dead and 33,782 injured. [1]

Several of Mukhina’s entries give vent to her hatred of the fascists, who perpetrated massacres and rapes in their advance, while reducing entire regions to rubble.

From November, the Nazis began the targeted bombing of bread factories, stockyards, large communal kitchens and electricity plants. Thus, by the winter — one of the coldest of the 20th century — the city’s food and energy supply networks had almost completely collapsed. Water emerged only occasionally from the pipes. Mukhina’s diary entries, which until then usually dealt with her political and personal worries and thoughts, increasingly focus on only two things: the cold and hunger. On November 21, her birthday, she has almost nothing to eat. The bread ration for pupils at this time is restricted to 125g—the equivalent of one extremely thin slice of bread. Apart from this, Lena, her aunt and Aka survive mainly on hot gruel and a few sweets.

On November 22, Mukhina writes:

“The gas supply has stopped, you can’t buy any kerosene, people cook their daily meal on the ovens fuelled with firewood and wood shavings. But most people are relying on the various canteens. Nowadays, hardly anyone goes down into the air raid shelters any more; they no longer have the energy to climb up and down the stairs due to systematic malnutrition.” [p. 146]

Like hundreds of thousands of others, hunger forces Mukhina’s family to kill their house pet, a tomcat, in December. By the end of the year, all dogs, cats and even rats and mice have disappeared from Leningrad.

Most of the blocks of flats are unheated. The extreme cold and malnutrition lead to widespread deaths. In December, nearly 40,000 people die; in January and February 1943, the figure reaches almost 100,000 each month. By the summer of 1942, a further 150,000 people die. There are outbreaks of cannibalism.

Aka and Lena’s aunt also waste away in the winter. Aka, who is already 76 and completely worn out by hunger, dies on January 1, 1942.

Mukhina’s diary entries become more and more despairing.

On January 3, she angrily writes:

“We are dying like flies here because of the hunger, but yesterday Stalin gave another dinner in Moscow in honour of Eden [British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden]. This is outrageous. They fill their bellies there, while we don’t even get a piece of bread. They play host at all sorts of brilliant receptions, while we live like cavemen, like blind moles.” [pp. 187-88]

Mukhina’s aunt dies in early February. She is desperate and on the point of dying from starvation. Only her aunt’s food cards, which she is able to continue using, enable her to survive.

Almost entirely on her own, Mukhina now makes plans to escape from Leningrad over the “road of life,” Lake Ladoga. She intends to go and live with relatives in Moscow.

By April, more than half a million people are evacuated over Lake Ladoga. Mukhina manages the escape probably around the end of May. Her diary suddenly ends on May 25.

From 1943, following the victory at Stalingrad, the Red Army was able to strike back at the Wehrmacht with several offensives, including one at Leningrad. However, the city was not completely liberated until January 27, 1944. By then, every third citizen of Leningrad had been killed and over a million Red Army soldiers had fallen in defence of the city.

After the war, Mukhina was unable—as she had once wished—to continue her education. She underwent training and worked at different factories. Like many survivors of the blockade, she suffered from serious medical problems for the rest of her life. She died in 1991, a few months before the Stalinist bureaucracy’s dissolution of the Soviet Union.

The high casualty figures of the blockade were anything but an unintended byproduct of the war. Rather, the extermination of the population in and around Leningrad was an integral part of the Nazis’ so-called “Master Plan East” [Generalplan Ost], on which the war of annihilation against the Soviet Union was based.

The planners of the Economic Staff East wrote: “Many tens of millions of people will be superfluous in this area [northern and central Russia] and will have to either die or emigrate to Siberia.” A total of 30 million Soviet citizens were to be abandoned to starvation.

The aim of the plan was to create “Living space [Lebensraum] in the East.” Germans were to be resettled in western Russia and eastern Europe in place of the “Slavs.”

The war of extermination in the East was also intended to ensure that the Wehrmacht and German population were adequately supplied with food, in order for Germany to win the war against Britain. This food was to come from Russia and Ukraine.

The “Master Plan East” was based on the military strategy and experiences of German imperialism in the First World War. Even then, Ukraine was to be brought under German control as the “breadbasket of Europe.” Like the military strategy against France, however, the one in the East failed. Enormous supply shortages led to mass starvation in the German Empire: approximately 800,000 people starved to death in Germany between 1914 and 1918. The widespread poverty and hunger were among the main driving forces of the German November Revolution of 1918/19, which was thwarted only by the betrayal of social democracy.

The Nazis wanted to avoid such a situation at all costs. Hermann Göring, commander of the German Air Force in World War II, played a major role in the decision of autumn 1941 not to conquer Leningrad, but to besiege it and starve it out. “If someone is to starve, it won’t be a German,” he declared.

The sieges of Leningrad and Moscow, as well as other major cities like Kiev, Kharkov and Sevastopol in Ukraine, were an integral part of this strategy. But nowhere was the blockade enforced so mercilessly as at Leningrad. Hitler himself said that the city was to be razed to the ground. There was no place for Leningrad, with its three-million-strong population, in the plans for “Germanised Russia.”

The city was significant in several respects. It was there that the first workers’ revolution in world history had taken place in October 1917. Leningrad was therefore of great symbolic importance to both the Soviet population and the Nazis. The latter wanted to destroy the Soviet Union and the achievements of the working class.

Moreover, Leningrad was the second largest industrial centre in the Soviet Union. The Nazis’ “strategy of annihilation” in western Russia and the major cities was primarily aimed at the working class. The port city of Leningrad was also important for strategic reasons. The Nazis wanted to conquer it in order to gain control over the Baltic region.

Notes

[1] Jörg Ganzenmüller: Das belagerte Leningrad 1941-1944: Die Stadt in den Strategien von Angreifern und Verteidigern [ Leningrad under siege 1941-1944: The City in the Strategy of its Attackers and Defenders ], Paderborn 2007, p. 66

[2] Quoted in ibid, p. 47

[3] Quoted in ibid, p. 63