The Dangerous Bias of the “Unbiased” About Fidel’s Cuba

When I wrote an article on Cuba’s philosophical traditions, a left-wing friend, also a friend of Cuba, said I should acknowledge and address Cuba’s alleged human rights violations. Unless I did that I was presenting Fidel Castro as a “Messianic figure”. I am not being objective.

Ideas are Cuba’s best gift to the world. Fidel Castro expressed them, in deed, speech and theory. If I write about something Canada does well, should I discuss the residential school programs, or the suicide epidemic among youth (even in rich southern Ontario). These matter deeply to the country’s self-conception. Yet no one will accuse me of bias if I leave them out writing about philosophy in Canada.

In the case of Cuba, any positive reference, no matter what the topic, without equal space for Cuba’s human rights violations, is considered unfairly biased.

To be objective, we consider opposing positions. But the reality is that there exist careful, informed arguments that: Cuba is democratic, Fidel is not a dictator, Cuba`s human rights violations are exaggerated and not as serious as many other countries. The point is not that the arguments are sound. It is that they exist. They are made by intelligent, morally responsible scholars. They are not silly.

So the question is: When the “unbiased” make routine references to Cuba`s human rights violations, do they address these arguments? Do they know about them? If they do not, they are guilty of bad argument, and unfair bias. This is just a point about scholarship. The human rights criticisms against Cuba have been answered over and over again, in the UN, in documentaries (e.g. Saul Landau’s Will the real terrorist please stand up?) and in entire books. The responses are ignored.

Nonetheless, I am required to repeat the criticisms, in order to be considered fair when I make an argument about the value of Cuba’s philosophical traditions.

When my students want me to be objective, they are asking me to be fair. I should not rely upon personal likes and dislikes regarding, for example, their appearance and personalities. However, they do want me to follow my preferences for clear writing, good argument and serious research. These are also values. They can also be called biases.

When I first spent time in Cuba, I was criticized for talking to members of the Communist Party. To be objective, I should talk to dissidents. I considered this criticism. It was true that I wasn’t spending time with dissidents, but it was not true that I disregarded their ideas. Such ideas inform institutions I’d lived with my entire life – the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), for example, which equates democracy and capitalism, never acknowledging, even remotely, opposing conceptions.

At that time, the Soviet Union had just collapsed, and Cuba had lost 85 percent of its trade almost overnight. The economic crisis was severe. It was easy to understand why people were discontented and why some were leaving for the US. It was much harder to understand those who refused to leave, who said they didn’t know where they were going but that they could not/would not turn back.

And there they were: warm, funny, likeable, and intelligent people, working for independence, without lights, pens, or enough food. I was more challenged by their stories than by those of the dissidents, which is not to disrespect the latter. I have spent more than two decades trying to understand what José Martí describes as the “heroism” of pursuing a line of thought “in an orderly way”, day by day, against the prevailing global orthodoxy. Even so, I am only beginning to understand.

Some researchers claim to make no value judgments. They listen to the stories of the people. I asked one in Cuba whether she interviewed members of the government or the Cuban Communist Party. She looked surprised and said no, not intentionally. She considered herself “non- judgmental,” and yet deliberately discounted some Cubans, without argument. Apparently this had not occurred to her.

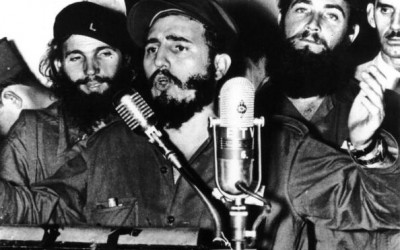

Wherever Fidel Castro went in the world, including to Canada for Pierre Trudeau’s funeral, people poured into the streets, in the hundreds of thousands, or more. The “unbiased” wouldn’t have known about these events because they weren’t reported by CNN or the CBC. The “unbiased” won’t find the explanation for them either because it is not consistent with the “balance” being “unbiased” requires.

Castro said once that there are two struggles. One is the social, political and economic struggle for justice and independence. The other is the struggle for the story that will be told about the first struggle. Some say the second one is harder. Chinua Achebe wrote that there are some who rush to battle and some who tell the story afterward. Some think it is easy to control the story. But, he says, they are fools.

Those who know the truth about the Cuban Revolution must do the hard work of the second struggle. It won’t be just Cubans. But whether in the North or the South the struggle won’t be unbiased. It shouldn’t be unbiased. It has to forge more adequate concepts – some philosophical – which means disturbing the balance of comforting liberal certainties. Fidel Castro’s ideas are a vehicle.

Sue Babbitt is associate professor of philosophy at Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada, and author (most recently) of Humanism and Embodiment (Bloomsbury 2014) and José Martí, Ernesto ‘Che” Guevara and Global Development Ethics (Palgrave Macmillan 2014)