The Coming Conflict in the Arctic

Russia and US to Square Off Over Arctic Energy Reserves

Russian President Vladimir Putin and U.S. President George W. Bush spent most of their time at the “lobster summit” at Kennebunkport, Maine, discussing how to prevent the growing tensions between their two countries from getting out of hand.

The media and international affairs experts have been portraying missile defense in Europe and the final status of Kosovo as the two most contentious issues between Russia and the United States, with mutual recriminations over “democracy standards” providing the background for the much anticipated onset of a new Cold War. But while this may well be true for today, the stage has been quietly set for a much more serious confrontation in the non-too-distant future between Russia and the United States – along with Canada, Norway and Denmark.

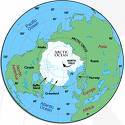

Russia has recently laid claim to a vast 1,191,000 sq km (460,800 sq miles) chunk of the ice-covered Arctic seabed. The claim is not really about territory, but rather about the huge hydrocarbon reserves that are hidden on the seabed under the Arctic ice cap. These newly discovered energy reserves will play a crucial role in the global energy balance as the existing reserves of oil and gas are depleted over the next 20 years.

Russia has the world’s largest gas reserves and is the second largest exporter of oil after Saudi Arabia, but its oil and gas production is slated to decline after 2010 as currently operational reserves dwindle. Russia’s Natural Resources Ministry estimates that the country’s existing oil reserves will be depleted by 2030.

The 2005 BP World Energy Survey projects that U.S. oil reserves will last another 10 years if the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is not opened for oil exploration, Norway’s reserves are good for about seven years and British North Sea reserves will last no more than five years – which is why the Arctic reserves, which are still largely unexplored, will be of such crucial importance to the world’s energy future. Scientists estimate that the territory contains more than 10 billion tons of gas and oil deposits. The shelf is about 200 meters (650 feet) deep and the challenges of extracting oil and gas there appear to be surmountable, particularly if the oil prices stay where they are now – over $70 a barrel.

The Kremlin wants to secure Russia’s long-term dominance over global energy markets. To ensure this, Russia needs to find new sources of fuel and the Arctic seems like the only place left to go. But there is a problem: International law does not recognize Russia’s right to the entire Arctic seabed north of the Russian coastline.

The 1982 International Convention on the Law of the Sea establishes a 12 mile zone for territorial waters and a larger 200 mile economic zone in which a country has exclusive drilling rights for hydrocarbon and other resources.

Russia claims that the entire swath of Arctic seabed in the triangle that ends at the North Pole belongs to Russia, but the United Nations Committee that administers the Law of the Sea Convention has so far refused to recognize Russia’s claim to the entire Arctic seabed.

In order to legally claim that Russia’s economic zone in the Arctic extends far beyond the 200 mile zone, it is necessary to present viable scientific evidence showing that the Arctic Ocean’s sea shelf to the north of Russian shores is a continuation of the Siberian continental platform. In 2001, Russia submitted documents to the UN commission on the limits of the continental shelf seeking to push Russia’s maritime borders beyond the 200 mile zone. It was rejected.

Now Russian scientists assert there is new evidence that Russia’s northern Arctic region is directly linked to the North Pole via an underwater shelf. Last week a group of Russian geologists returned from a six-week voyage to the Lomonosov Ridge, an underwater shelf in Russia’s remote eastern Arctic Ocean. They claimed the ridge was linked to Russian Federation territory, boosting Russia’s claim over the oil- and gas-rich triangle.

The latest findings are likely to prompt Russia to lodge another bid at the UN to secure its rights over the Arctic sea shelf. If no other power challenges Russia’s claim, it will likely go through unchallenged.

But Washington seems to have a different view and is seeking to block the anticipated Russian bid. On May 16, 2007, Senator Richard Lugar (R-Indiana), the ranking Republican on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, made a statement encouraging the Senate to ratify the Law of the Sea Convention, as the Bush Administration wants. The Reagan administration negotiated the Convention, but the Senate refused to ratify it for fear that it would unduly limit the U.S. freedom of action on the high seas.

Lugar used the following justification in his plea for the United States to ratify the convention: “Russia has used its rights under the convention to claim large parts of the Arctic Ocean in the hope of claiming potential oil and gas deposits that might become available as the polar ice cap recedes due to global warming. If the United States did not ratify the convention, Russia would be able to press its claims without the United States at the negotiating table. This would be directly damaging to U.S. national interests.” President Bush urged the Senate to ratify the convention during its current session, which ends in 2008.

The United States has been jealous of Russia’s attempts to project its dominance in the energy sector and has sought to limit opportunities for Russia to control export routes and energy deposits outside Russia’s territory. But the Arctic shelf is something that Russia has traditionally regarded as its own. For decades, international powers have pressed no claims to Russia’s Arctic sector for obvious reasons of remoteness and inhospitability, but no longer.

Now, as the world’s major economic powers brace for the battle for the last barrel of oil, it is not surprising that the United States would seek to intrude on Russia’s home turf. It is obvious that Moscow would try to resist this U.S. intrusion and would view any U.S. efforts to block Russia’s claim to its Arctic sector as unfriendly and overtly provocative. Furthermore, such a policy would actually help the Kremlin justify its hardline position. It would certainly prove right Moscow’s assertion that U.S. policy towards Russia is really driven by the desire to get guaranteed and privileged access to Russia’s energy resources.

It promises to be a tough fight.