The CIA’s Involvement in Indonesia and the Assassinations of JFK and Dag Hammarskjold

Commemoration of the Assassination of John F. Kennedy, November 22, 1963

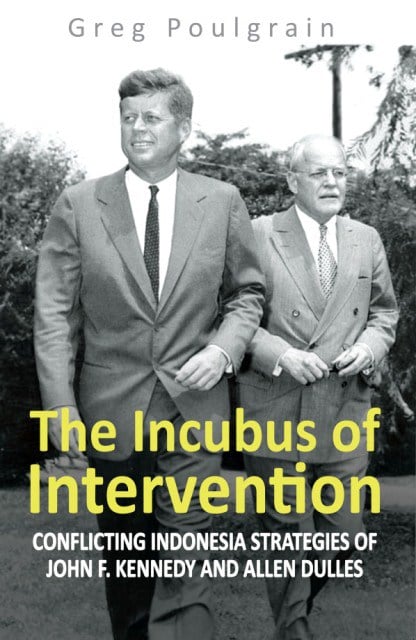

The truth about Indonesian history and the United States involvement in its ongoing tragedy is little known in the West. Australian historian, Greg Poulgrain, has been trying for decades to open people’s eyes to the realities of that history and to force a cleansing confrontation with the ugly truth. It is a story of savage intrigue that involves the CIA and American governments in the support of regime change and the massive slaughter of people deemed expendable. In his latest book, The Incubus of Intervention: Conflicting Indonesia Strategies of John F. Kennedy and Allen Dulles, Poulgrain shows how President John Kennedy tried to change American policy in Indonesia but was opposed by Allen Dulles and the CIA, resulting in JFK’s murder. Kennedy’s death, preceded by that of UN Secretary- General Dag Hammarskjold, then led to the US backed murder of millions of Indonesians, Papuans, and East Timorese.

While an academic historian with meticulous credentials, Poulgrain is also a rare bird: a truth teller.

In this interview, he greatly expands on many issues in his books, including Allen Dulles’s and Kennedy’s conflicting strategies regarding Indonesia, Dulles’s involvement in the assassinations of JFK and Dag Hammarskjold, CIA involvement in the ouster of Indonesian President Sukarno, and the subsequent slaughters throughout Indonesia and West Papua.

For people of conscience, his is a voice worth heeding.

In the introduction to The Incubus of Intervention you ask the question: “Would Allen Dulles have resorted to assassinating the President of the United States to ensure his ‘Indonesian strategy’ rather than Kennedy’s was achieved?” You say it is up to the reader to decide and that is why you have written the book. There is a bit of ambiguity in that second statement. What have you concluded?

Slowly, slowly… I came to understand the role of Indonesia in the differences that emerged between Allen Dulles and John F Kennedy. My lecturing/research on Indonesian history and politics, which I’ve now been doing for several decades, kept me on track. A memorable interview with Indonesian former vice-president, Adam Malik, less than a year before he died, left me puzzled as to why he wanted to impress on me the importance of Indonesia in relation to the Sino-Soviet rift. I did not realize until much later that, once the rift was detected, Indonesia was used by Allen Dulles as a wedge to split them further apart.

Visiting Indonesia from Brisbane is much less of an expedition than travelling from the USA so, over the years, I’ve spoken with many people there about Sukarno and the politics of the ‘60s. Although I include 19th and 20th century history as part of the history I teach, my focus remains the 1950s and 60s, when Indonesia was struggling to find its feet as an independent country. The Dutch had remained for more than three centuries because they were presiding over the world’s richest colony.

Visiting Indonesia from Brisbane is much less of an expedition than travelling from the USA so, over the years, I’ve spoken with many people there about Sukarno and the politics of the ‘60s. Although I include 19th and 20th century history as part of the history I teach, my focus remains the 1950s and 60s, when Indonesia was struggling to find its feet as an independent country. The Dutch had remained for more than three centuries because they were presiding over the world’s richest colony.

Before the war in Vietnam reached full pitch, Washington’s attention was on Laos. Allen Dulles had long been keeping an eye on Indonesia but in government policy or official announcements Indonesia rarely received any mention at all, despite its political volatility, its immense wealth of natural resources and the sheer size of the country. It is many times larger in population than most countries in Southeast Asia – the 4th largest in the world – and as the world’s longest archipelago it is slung across the equator for a distance equivalent to that between Los Angeles and Newfoundland.

The Indonesian populace in 1963 considered JFK a hero, during and after his presidency; so the fact that his strategy to bring Indonesia ‘on side’ in the Cold War is not well known outside Indonesia really highlights our lack of awareness of Indonesia. And how many readers are aware of Allen Dulles’ covert operations in Indonesia? – such as in 1958, which was the largest CIA operation outside Vietnam according to Colonel Fletch Prouty who once worked alongside Dulles. I am assuming the reader is not familiar with Indonesia of the 1960s and even less familiar with the respective strategies of Kennedy and Dulles, so I really have to throw some light on these to enable the reader to see there is startling evidence linking the two, centered on Indonesia. It was an extraordinary political duel, and the triumph of Dulles led not just to the death of Kennedy but to the death of millions. It is on-going…

Could you share with us this background and their respective strategies?

The potential wealth of the archipelago, particularly oil and minerals, caught the attention of Allen Dulles as a lawyer in the 1920s. He was representing Rockefeller Oil interests against Henri Deterding, the legendary oil mogul of the Netherlands East Indies. Having first started in Intelligence at the time of the First World War, Allen Dulles was still closely linked with Rockefeller oil interests when he became DCI (Director of Central Intelligence) in the 1950s. His expertise was regime change and this was his ultimate aim in Indonesia. His anti-Sukarno strategy had begun more than three years before John F. Kennedy was elected president, and it came into conflict with Kennedy’s pro-Sukarno stance. Kennedy’s Indonesia strategy involved befriending Indonesia as a Cold War ally as this was a prerequisite for Kennedy’s Southeast Asian policy dealing with Laos and the burgeoning problem of North and South Vietnam. In 1961, Dulles did not reveal to Kennedy the depth and intricacy of subterfuge he’d initiated with Indonesia as the focus, nor was Kennedy aware of the extent and elaborate nature of Dulles’ strategy.

Was Allen Dulles’s Indonesian strategy just about Indonesian oil and mineral wealth?

The Cold War was raging in the early 1960s with Washington pitted against the Sino-Soviet bloc. Driving a wedge between Moscow and Beijing was one of the resolutions of the Rockefeller Brothers panel when it met in 1958 – the panel which included persons such as DCI Dulles and his former associate from postwar Berlin, Henry Kissinger, whose concept of ‘limited nuclear war’ was attracting attention. When an ideological split between Moscow and Beijing was confirmed in the early 1960s, Dulles regarded this intelligence as so vitally important that he informed neither the ailing incumbent president, Eisenhower, nor the Secretary of State who took over in 1959 from John Foster Dulles (Before dying of cancer, John Foster refused his younger brother Allen the privilege of stepping into his shoes as Secretary of State, Allen’s lifelong ambition.)

Nor did Allen Dulles inform the new president, John F Kennedy, that the Sino-Soviet split was real. During his first year in office in 1961, Kennedy all too soon became Dulles’ nemesis. During the second year, with Dulles still as powerful as ever but no longer DCI, the Cold War reached its apogee with the Cuban missile crisis. In the third year of Kennedy’s presidency he intended to implement his Indonesia strategy so as to justify his intervention in the New Guinea sovereignty dispute. In essence, this involved pouring in US aid in order to turn Indonesia towards the West. Kennedy had intended using the same Indonesian army officers which Dulles had been training at US bases since 1958, training in readiness to assume power. Kennedy’s intention to utilize these same troops for massive civic aid programs was the very opposite of Dulles’ intention. But most of all, Kennedy intended to keep Sukarno as president whereas in Dulles strategy Sukarno was the arch-enemy. Under the aegis of Sukarno’s radical nationalism, the Indonesian communist party had been gathering millions of members, driven by poverty and the attraction of owning a small patch of land to grow rice.

I am reminded of how Dulles, who was so treacherous, also didn’t inform Kennedy that the CIA had learned that the Soviets knew of the date of the Bay of Pigs invasion more than a week in advance and had informed Castro. So Dulles knew the invasion would fail but went ahead with it anyway. He then blamed Kennedy. He was devious beyond belief.

A former head of British intelligence once described Allen Dulles as the “greatest intelligence officer who ever lived” and while this comment referred to his activities in the 1940s his Indonesia strategy certainly supports the accolade. Dulles became aware of the bonanza of minerals and oil in Netherlands New Guinea before the Japanese wartime occupation of Indonesia. In the mountains of New Guinea one of the Rockefeller companies discovered the world’s largest primary deposit of gold. In addition to this, the oil that was discovered in record quantity was free of sulphur (so oil-refining was not required).

However, to gain control over these natural resources, first the Dutch colonial administration had to be removed. When Dutch colonial rule in the Netherlands East Indies ended in 1949, the Dutch retained New Guinea and stayed another twelve years. Dulles helped Kennedy to choose in 1962 between Dutch or Indonesian rule over the Papuan people – he chose the latter- by ensuring the UN option would not occur. The UN option involved secret discussions in 1961 between Kennedy and the UN Secretary-General, Dag Hammarskjold. Kennedy favoured intervention by the UN because it meant he would not have to choose between Indonesia (whom he needed as a Cold War ally in Southeast Asia) and the Dutch (who were NATO allies). Hammarskjold was going to deny both Dutch and Indonesian claims to sovereignty and instead grant the Papuan people independence.

The thought of Papuan independence must have incensed Dulles.

‘The Incubus of Intervention’ shows how and why Allen Dulles prevented Dag Hammarskjold from using the United Nations to bring the New Guinea sovereignty dispute to an end. Dulles’ intervention and the death of Hammarskjold is a ghastly precedent for the tragedy that occurred when JFK’s proposed visit to Jakarta was stopped in Dallas. Kennedy’s visit – as Dean Rusk explained to me in a hand-written letter – was to bring Malaysian Confrontation to a halt and this would only have reinforced Sukarno’s position as ‘president for life’. Kennedy’s proposed visit meant the death of Dulles’ Indonesia strategy.

Had the vast gold and copper deposits in the mountains of West New Guinea (West Papua) remained under the control of President Sukarno, they would have been used primarily to benefit the Indonesian people. The opposite occurred once Indonesia was under the control of General Suharto – indeed, outside the building in Jakarta when the contract was signed with the Rockefeller company, Freeport Indonesia, army tanks were heard patrolling the streets. Vast oil deposits in Sumatra, and oil in other parts of Indonesia, were also exploited. Two of Dulles’ close associates later benefited from the bonanza of natural resources – Admiral Arleigh Burke of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and Kissinger joined the Freeport board of directors. When the price of gold was at its height several years ago, the size of the Freeport mining operation could be gauged by the annual turnover which was almost $20 billion.

Do you think Kennedy’s Indonesian strategy would have worked?

Kennedy’s Indonesia strategy would have worked: that was the problem facing Allen Dulles. Stopping Malaysian Confrontation quite possibly may have landed him a nomination for the Nobel Peace Prize. Had he not attempted to secure his Indonesia strategy – that is, had he not been prepared to go to Jakarta to stop Confrontation in order to get Congress to resume US aid to Indonesia, winning the 1964 presidential elections would have been next to impossible. His major foreign policy move in Southeast Asia would have been deemed a failure, so he had no option.

It was easy for Kennedy’s detractors to depict his Indonesia strategy as driven by personal political ambition, because the key factor was that he was supporting President Sukarno; and because Sukarno had received such bad press in the USA, such a move by Kennedy seemed fraught with political danger. Sukarno throughout his entire political career back to the 1920s had promoted nationalism but still he was branded by some as a communist, or communist sympathizer; even Kennedy, for that matter, was labelled by some extremist media as a communist. For Dulles’ Indonesia strategy to receive sufficient support from persons in the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Kennedy’s personal ambition was seen as cutting across the national interest, disrupting the strategy of using the Indonesian army as a political vehicle against the Indonesian communist party, the PKI. Both Moscow and Beijing were endeavouring to gain influence on the PKI, the latter by promoting the PKI role in Malaysian Confrontation, and the former by discouraging the PKI from participating; instead, Moscow preferred elections to be held so the numerical advantage of the PKI could be brought to bear. The rivalry between the two was intense, and ideological disputes were increasingly evident. Kennedy’s visit would have closed down the opportunity to use the PKI as a wedge to drive the Sino-Soviet dispute into open hostility.

After the PKI was decimated in late 1965-66, under orders from General Suharto’s military cohorts, open hostility flared in the form of tank battles along the Sino-Soviet border. Had Kennedy proceeded with his visit to Jakarta and his Indonesia strategy succeeded, we can only surmise whether or not the Sino-Soviet dispute would have turned into such open conflict or whether the tragic turn of events in Indonesia, 1965, would ever have occurred. Or would General Suharto like a toadstool have found another way to surface.

You do not say if you have concluded that Dulles had JFK assassinated because of the Indonesia issue. What is your position on that?

Have you seen that 50-minute interview on Youtube by Colonel Fletcher Prouty where he says his former CIA boss, Allen Dulles, in his last few year as Director, was organizing assassinations so regularly and so ruthlessly that Prouty called it “Murder Incorporated” ?

Yes. Prouty’s insights are invaluable.

For example, take the plane crash which killed UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjold in the Congo in 1961. Last year, 2015, a UN investigation finally decided his death was political assassination. Playing a crucial role in this investigation were documents (ten letters by a South African intelligence agency) unearthed by Archbishop Desmond Tutu in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in the late 1990s. The name of Allen Dulles was directly linked with the plane crash.

The interview I conducted with Hammarskjold’s right-hand man, George Ivan Smith, which is included in ‘The Incubus of Intervention’ introduced another motive – Indonesia rather than the Congo – for the involvement of Allen Dulles in the tragic death of Hammarskjold.

Can you talk about that interview? What you write about the Hammarskjold assassination, JFK, and Indonesia is new and very important.

George Ivan Smith explained that Hammarskjold was planning to make an historic announcement in the General Assembly when he returned from the Congo – which he never did. The announcement he had intended was for the United Nations to intervene in the long-running dispute between Indonesia and the Netherlands over sovereignty of West New Guinea. Had Hammarskjold done this, he would have totally disrupted the ‘Indonesia strategy’ of Allen Dulles. The CIA had already assassinated the first president of the Congo after being granted independence: this is what the US Senate investigated in 1975 and found Allen Dulles was directly involved in instigating this assassination.

What George Ivan Smith told me – combined with the evidence from Bishop Tutu – provided a motive for Allen Dulles’ involvement in the death of Hammarskjold that was centred on Indonesia rather than the Congo.

What I am saying is that in 1961 Hammarskjold unwittingly threatened Dulles strategy and that in 1963 Kennedy also threatened Dulles strategy without being fully aware of what Dulles was planning or the years of covert scheming that had gone into that planning. This is what I have labelled the ‘Indonesia strategy’ of Allen Dulles. By 1963, with Netherlands New Guinea and its unannounced bonanza of natural resources now a part of Sukarno’s Indonesia, Dulles’ strategy was on several levels which I’d like to restate:

1) It involved using Indonesia, or the Indonesian communist party (PKI ) as the ‘wedge’ to widen the rift between ‘Moscow and Peking’ (Beijing)

2) Dulles’ intervention in Indonesia in 1958 led to full-scale training in the USA of two-thirds of all Indonesian army officers, in readiness for regime change (which came in 1965)

3) Exploitation of the world’s largest primary deposit of gold (and copper) in West New Guinea, and the world’s purest oil, with no sulphur, was a boost for Rockefeller companies (linked with Dulles since the 1920s.)

So the answer to your question is ‘yes’ – Indonesia offered immense benefits in terms of the Cold War struggle, and (when regime-change took place in Indonesia) immense benefits in terms of gold, copper and oil. (West New Guinea also has one of the world’s largest deposits of natural gas.)

Neither Hammarskjold nor Kennedy was aware of how high the stakes were and neither had more than an inkling of how ruthless Dulles could be. The Indonesia context, firstly in 1961 and then again in 1963, provided a motive for murder – first Hammarskjold and then Kennedy.

I have often thought of Kennedy and Hammarskjold as linked by a certain astute intelligence and a spiritual dimension. So Dulles had them both killed?

Official records show DCI Dulles often used gambling metaphors when weighing up the chance of success for correctly predicting what some foreign leader would do, or predicting the outcome of one of Dulles’ own projects. For instance, he’d say there was a “better than even” chance of success. After Hammarskjold’s plane crash in 1961 prevented the UN Secretary-General from interfering in the Indonesia strategy which Dulles had set in motion five years earlier, inexorably moving towards regime change, by 1963 the cumulative evidence confirming the rift in the Sino-Soviet bloc made a successful outcome of this strategy even more critical. In 1963 Kennedy’s proposed visit to Jakarta, while threatening to undo years of intelligence work on the massive amount of natural resources in Indonesia that would be accessible after regime change, also threatened Dulles’ Cold War machinations. Had Kennedy proceeded, the current Dulles’ strategy of using Indonesia as a wedge in the Sino-Soviet split would be undermined. Malaysian Confrontation, by sending the Indonesian economy into screaming inflation, was working in two ways for Dulles: while it set the scene for the exit of Sukarno, at the same time, it added to the rift and rivalry between Moscow and Beijing. As such, Kennedy’s visit to Jakarta could be seen as contrary to the national interest, and for the Joint Chiefs of Staff this carried far more weight. Stopping Kennedy became an imperative for Dulles. Having removed Hammarskjold, Dulles’ options now – to use his own inimitably callous metaphor – were “double or nothing.”

Could we jump ahead to the 1965-6 period when regime change took place and the slaughter commenced? What can you tell us about the killing of the generals, where the blame lay, Suharto’s links to the CIA, etc.? I know you have delved deeply into that.

Killing the army generals (rather than kidnapping and taking them to Sukarno to explain rumours of a coup) was not on the agenda of the 30th Sept Movement, according to one of the key persons in the Movement, Colonel Abdul Latief. Killing them changed everything – changed Indonesian history, led to General Suharto taking power and wreaking mayhem, one of the largest mass-murders in the 20th century. The Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) under DN Aidit was the largest communist party outside the Sino-Soviet bloc, and its decimation was a turning point in the Cold War. The serious discord between Moscow and Beijing, identified six years earlier and closely monitored by the CIA, was made far worse by the fate of the PKI. What had once been described as a monolithic communist bloc now had Moscow and Beijing hurling blame and abuse at each other and this soon led to open hostility (eg. tank battles on the Ussuri River.) The continued war in Vietnam, despite US losses, served this same end. In the early 1970s, the population of Beijing was even subjected to trial-runs in the event of nuclear attack from the Soviet Union involving mass-evacuation of the streets into underground shelters.

I know you spoke to Latief. What did he tell you?

My interview with Colonel Latief was in Cipinang prison a few days after Suharto resigned. I’d arrived in Jakarta in May 1998, just after the rioting and burning had started – the last person through the airport before it was closed – and became involved in the supply-chain delivering food to the 60,000 Indonesian students who were occupying the parliament building. Student protest did much of the work (up to the final thumbs-down by US Secretary of State, Madeleine Albright) which forced the resignation of Suharto. One of the students who also delivered food to persons in prison – such as Latief, who had been in prison for 30 years – helped me into Cipinang.

The three main army persons in the 30th Sept Movement were Latief, Untung and Supardjo. Latief was commander of the Jakarta military command. It was essential to have him on side for the plan to kidnap half a dozen generals. “There was no plan to kill the generals, no plan to kill anybody,” Latief repeated to me several times. The person described as head of the Movement was Lt. Colonel Untung, commander of the palace guard; but the highest ranking officer was Brig-General Supardjo, based in Pontianak, Kalimantan, as part of the on-going confrontation with Malaysia. He’d been asked over to Jakarta by General Suharto (who was running the Confrontation campaign) but the first person he visited when he arrived was Sjam (full name Kamaruzaman) who was the actual leader of the Movement. This visit by Supardjo was only two days before the kidnapping began. His higher rank as general added respectability to the Movement and he acquiesced in the plan to move against the ‘Council of Generals’ accused of planning a coup against President Sukarno. He could see the Movement lacked any coherent strategy or military planning, but as such an urgent threat needed immediate response he was willing to let it proceed. It cost him his life.

John Roosa’s book, Pretext for Mass Murder, confirms Sjam was the leader of the Movement. Roosa explains Sjam’s role in relation to the Special Bureau, a covert group within the PKI which Aidit started in late 1964 to befriend persons in the armed forces who might have been supportive of the PKI. Since the early 1950s, Aidit had known of Sjam’s skill in becoming involved in an issue from both sides of the political fence and obviously thought he was the man for the job, even though he had no formal military training. Apparently what Aidit did not know was that Sjam’s military experience during the 1945-49 struggle for Indonesian independence against the Dutch involved close contact with Suharto. Nor did Aidit realize the implications of this military bond which predated his own link-up with Sjam: indeed, it should raise serious questions about Aidit’s control over Sjam in the Special Bureau when Sjam’s ultimate allegiance was to Suharto.

Did Suharto support this group?

Among the members of the 30th Sept Movement, there was no question that Suharto discretely supported the group but it did not dawn on them that Suharto and Sjam may have been operating together as one unit.

So why did they trust Suharto?

When I asked Latief why the Movement trusted Suharto so much before the fateful night when the generals were kidnapped, he answered as follows: “He was one of us”….. Latief and Suharto were close friends. They had family links and military ties that went back to the 45-49 independence struggle, where Latief briefly met Sjam for the first time, but the Suharto-Sjam link during the 1950s leading up to Sjam’s role in the Movement remained unknown to Latief – until it was too late and the killings had occurred. Latief said when he was thrown into prison, the bullet shot into his knee was left untreated, and he was also stabbed with a bayonet. At first he was left without food in prison; he told me he was so hungry he caught a rat and ate it.

In retrospect Latief’s evidence makes a mockery of the court proceedings: after all, he had visited the house of Suharto a few days before the kidnapping to explain to Suharto the plan to kidnap the generals. Any such operation would have been stomped on immediately by Indonesia’s strategic command, Kostrad, but this did not happen because the commander of this elite unit was Suharto himself. If it could be argued that Suharto kept this information to himself for the ultimate benefit of Indonesia, then he must also accept responsibility for the death of the generals – which opened the path to the presidency for none other than the ultimate benefit of Suharto. On the morning of 1st October when troops from the Movement occupied Merdeka Square, a central location in Jakarta, the fact that Suharto’s Kostrad headquarters remained untouched even after the first radio announcement was tantamount to a statement of alliance between him and the 30th September Movement. On one side of the square was the US Embassy, on another side was Kostrad headquarters, and opposite was the Radio station from where the Movement made its first announcement at 7.15am that a number of generals had been arrested and that an Indonesian Revolutionary Council would be established in Jakarta. The ten-minute broadcast gave the name of Untung as leader of the Movement.

According to another person I interviewed, Indonesian Air Force intelligence officer Lt. Colonel Heru Atmodjo, who was accused of involvement in the Movement and spent 17 years in prison, the first radio announcement was written by Sjam but perused and approved by Untung, whereas the second radio announcement just after midday was entirely the work of Sjam. The second radio announcement was attempting a dramatic restructuring of rank and power – while all the time holding Sukarno as the supreme commander – and as a result of this announcement the Movement has subsequently been labelled as attempting a ‘coup’. Only in hindsight did Latief realize the Movement which he had supported was actually politically motivated or – one might say – infected by the presence of Sjam.

In his defence statement, Latief told the court not only that he visited the house of Suharto a few days before 30th Sept and outlined the plan, but also that they spoke again on the night of 30th September when Suharto was visiting his son in hospital. The court dismissed Latief’s remarkable information as irrelevant. Nor was the court told that, after hearing from Latief that the kidnapping operation would take place that very night in the early morning hours of 1st October, Suharto then paid a secret visit to the official residence of Brig-General Supardjo at Cempaka Putih, in Jakarta. (He also had a family home in Bandung.) The late-night secret visit was witnessed by a Lt. Colonel who took note but did not mention it, of course, during the subsequent years of terror under Suharto. More than two years before Suharto’s resignation, a very high-ranking Indonesian officer, together with a prominent politician, informed me of this visit by Suharto to the residence of Supardjo. Suharto not only knew of the plan to kidnap the generals but was accepted as one of the group.

How and when did Suharto manipulate the kidnapping and murder of the generals as a pretext for the slaughter of the PKI?

A remarkable PhD thesis completed in June 2014 by J. Melvin, ‘The Mechanics of Mass Murder’, shows how Suharto, on the morning of the 1st October 1965, had issued orders to begin arresting and culling the PKI in faraway northern Sumatra. Before the PKI had even been named as possible culprits – indeed, even before it was known that the fate of the generals was not kidnapping but murder – Suharto was blaming the PKI for the deaths of the generals. He issued orders for retaliation against the PKI. When this gruesome preparatory work of Suharto becomes better known (and I think John Roosa will soon publish another book incorporating this vital information) the role of Suharto in the death of the generals will be seen as his ‘crossing the Rubicon’ – but in this case it was a river of blood.

Suharto’s intelligence aide, Ali Murtopo, later tracked down two of the drivers of the trucks which had transported the troops involved in the kidnapping and murder. Murtopo killed both drivers a week or so later, perhaps because they had information which, in some way, might have linked Suharto to Sjam, or information relating more directly to the death of the generals.

Sjam admitted in court his responsibility for the death of the generals – during the kidnapping the last-minute orders were ‘dead or alive’ and those who survived the kidnapping were later executed with a bullet in the head – but Sjam claimed all this was on instructions from Aidit, bolstering the case that the PKI was responsible.

Taomo Zhou has shown in her article ‘China and the Thirtieth of September Movement,’ (‘Indonesia’ 98,October 2014) that the transcript of a discussion between Chairman Mao and Aidit bears remarkable resemblance to what took place in Jakarta on the fateful night when the six generals were killed – the event which Indonesian terminology refers to as G30S. However, the transcript is historically contaminated by the murderous events that took place on the night of 30th September. With G30S in hindsight, Aidit’s complicity can be read into the transcript to such an extent that kidnapping is all too readily replaced by murder. Taomo Zhou states that “The Chinese leaders were aware of the PKI’s plan to prevent the anti-Communist army generals from making a move to seize power “- but murder (as Latief explained) was not on the agenda, so to attribute any more than kidnapping into Aidit’s intention would seem to be reading into the transcript more than intended in the original meaning. Because of the way the term G30S is used in the summing up, Taomo Zhou implies murder was on the agenda: “Recent research indicates that a clandestine group within the PKI, which included Aidit but excluded other members of the politburo and the rank and file of the party, planned G30S.” And again: ”A clandestine group within the PKI independently made the plan, which was then shared by Aidit with the top Chinese leaders in advance.”

If Aidit is to be held responsible for the events which took place that night – and by this I mean the killing rather than the kidnapping of the generals – and that Sjam was acting on Aidit’s orders, then it would have been on Aidit’s instructions that G30S troops did not occupy Kostrad headquarters because Suharto was considered as one who was supporting the Movement.

Although Aidit did not mention any name, it may well have been the highest ranking officer (ie. Suharto rather than Supardjo) whom he was referring to when he told Chairman Mao “we plan to establish a military committee… The head of this military committee would be an underground member of our party.” The duplicity of Suharto, like Sjam, went a long way back into Indonesia history. In 1948, Suharto was the emissary sent by General Nasution to investigate the military strength and political unity of the movement in Madiun who, apparently under communist leadership, were steadfastly unwilling to conduct negotiations with the Dutch. “Do you negotiate with a burglar in your house?” was one of the rhetorical questions asked at this time. Suharto supported the intransigence of the left-wing groups in Madiun and, according to the military commander of Madiun, Soemarsono, (now 96 years of age and living in Sydney, where I spoke with him three months ago) Suharto was accepted by the PKI when he was in Madiun because of his strongly pro-left stance. Perhaps this was why Aidit, who in the postwar days was a young left-wing figure and only became head of the PKI in the early 1950s, was willing to accept the purported hand of friendship Suharto offered as Kostrad commander in Jakarta in 1965.

Suharto’s deviousness is breathtaking.

General Nasution knew Suharto over a period of two decades, from the days of the struggle for independence to 1965, and then for another three decades when Suharto was president. (Nasution 1918-2000 passed away two years after Suharto resigned.) Over a period from 1983 up to 1996, I visited Nasution many times to talk over aspects of Indonesia history. Hanging on the wall next to where we talked was a painting of his young daughter who was accidentally shot on the night of 30th Sept 65 when troops came to kidnap him, but failed. He escaped by climbing over the fence into an Embassy which was next to his house, but in the fracas his daughter was killed and so too was his adjutant, Lt Tendean. Nasution told me – without putting it in so many words – that his wife always blamed Suharto for the death of their daughter: for the rest of her life – that is, three decades of living in Jakarta – she never again spoke to Suharto.

Suharto has always claimed he had no prior knowledge of what the 30th Sept Movement was intending to do. Indeed, according to the three-tiered system he himself introduced to apportion blame, anything less than complete denial would have seen Suharto himself in Category One which was ‘prior knowledge’ and punishable by death.

What was Suharto’s link to the CIA and the 30th September movement?

When I asked Nasution about the role of the CIA, if any, in G30S, he told me that Sjam and Suharto had been observed in Bandung (where the Indonesian army has an officer training school, referred to as SESKOAD) visiting the commander of that school. The name of the commander was Colonel Suwarto and he was closely allied with the CIA, a detail Nasution stressed and one that is generally known by Indonesian scholars of this period. For me, Suwarto was an interesting character – quite apart from the fact that he had a wooden leg – because his American friend was Guy Pauker, well known as a close associate of Allen Dulles. When I asked Pauker if he’d met Suharto before he was president, he denied that he had. However, Pauker commented that Allen S. Whiting (his former friend in RAND and later State Dept Counselor) was the first person to point to the incipient split between Moscow and Beijing as a definite schism. Even in 1963 there were still relatively few who interpreted this split as genuine, but among those who did was Ambassador Marshall Green. [see: footnote 65 in Harold P. Ford’s article ‘Calling the Sino-Soviet Split’ published by CSI, Winter ‘98-99]. Having arrived in Jakarta in 1965 only months before the 30th Sept Movement, Green arranged for the Indonesia army to receive top-level communication gear to coordinate the widespread massacre of the PKI. Also supplying thousands of names, Green’s macabre contribution to the Cold War was, in effect, the decapitation the PKI.

Nasution’s own intelligence cohorts would have been the source of the reported sighting of Suharto and Sjam in Bandung. Assuming this is correct and Pauker’s denial also correct, then Suharto and Sjam might have been talking with Suwarto in one room, with Pauker in the adjacent room: a highly improbable situation, of course. Suwarto was the former instructor of Suharto when he attended SESKOAD, shortly before being appointed commander of the campaign to oust the Dutch from Netherlands New Guinea. (Today this Indonesian province, West Papua, has been controlled by the Indonesian army virtually since the signing of the New York Agreement in 1962, arranged by Allen Dulles’ long-term friend, Ellsworth Bunker.)

I’d like to point out something that emerged as a result of the interview with Colonel Latief. When going through the court testimonial of Sjam, some details he provided deserve closer attention as they are contradicted by Latief’s statement – and he was very adamant when he made the statement to me in Cipinang – that he had never seen Sjam before 30th Sept 1965. Yet in Sjam’s court evidence, he states that when Aidit and he set up the Special Bureau to ascertain or pinpoint persons in the army who might be sympathetic to the PKI position, this process involved a few meetings. Sjam claimed he held several meetings with Latief and Untung, and that the purpose of the meetings was to plan a counter-move to the so-called Council of Generals who were planning to move against President Sukarno. This is clearly incorrect if Latief had never met Sjam before 30th Sept. Rather than simply say, ‘Well, perhaps Latief is not correct,” another way to view this is to ask, ‘How was it that Suharto was a close friend of the four main persons in the Movement, Supardjo, Sjam, Untung and Latief?’ (Untung had served in the New Guinea campaign to oust the Dutch in 1962, with Suharto as his commanding officer.) Is there not also a possibility that Suharto, using his long-standing friendship with Untung and Latief and his inside-knowledge of where their political sympathies lay, actually suggested to Sjam (as part of his Special Bureau work) to approach Untung. And then for Untung to approach Latief. If this were the case, then we have a situation where Latief would have visited the house of Suharto in the days prior to G30S, to tell him of the action the Movement intended to take, when Suharto actually knew already. This may have reinforced Latief’s perception that Suharto’s role was supportive only, with no link between Sjam and Suharto, and so may have been a reason why Suharto did not have Latief executed, as he did the others in the Movement.

So you have concluded that Suharto was, together with the CIA, the puppeteer behind it all?

Increasingly, as further evidence is compiled years after the event, Suharto is taking on the appearance of the Kostrad commander at the centre of a web. He had made plans – even before the event occurred – to strike at the PKI for the events which occurred on the night of 30th Sept. And through Sjam he was able to ensure the kidnapping event (as planned by Latief, Untung and Supardjo) was turned into the murder of the generals; and through Sjam’s position with Aidit, Suharto ensured the event was turned into a tragedy of epic proportions, from which Indonesia has yet to recover.

So Suharto comes to power, the massacres ensue, and West Papua is exploited by American mining giant Freeport McMoRan. After all these years, do you see any hope for West Papuan independence?

The main issues facing the Papuan people in the western half of New Guinea, now two Indonesian provinces called Papua and West Papua, all stem from the continuing presence of the Indonesian army. Although there are Papuan regional representatives and a Papuan governor of each province, the Indonesian army rules everyday life, as it has since it first arrived in the territory in December 1962.

Ousting the Dutch colonial power in 1962, the Indonesian rule arrived in the form of an army of occupation and – although it is not as obvious to the casual observer now as it was during the Suharto era – the mentality of occupation, exploitation and annihilation has continued to the present day.

I am not using the word ‘annihilation’ as a simple descriptive term. The word ‘genocide’, of course, is abhorrent, and people visiting Papua/West Papua today would see Papuans in urban areas apparently living freely, and in the more remote regions Papuans still live in villages much as they did during and before the brief Dutch period. Yes, there have been some positive changes but in terms of infant mortality and other important life-indices, the statistics for the quality of life lived by some indigenous Papuans are worse than the worst in Africa. This is precisely what angers the Papuan people. They are 20 times the national average of HIV-Aids and the usual response from Jakarta is that the Papuans are primitive and their sexual practices have led to the shocking statistics. But the reality is – and here I can speak from personal experience having interviewed a medical officer who had investigated the problem – the Indonesian army has been responsible for bringing prostitutes to Papua (as part of the varied business interests of the army in Papua) and ensuring all the prostitutes – they came from Surabaya – were HIV-infected. The medical officer actually interviewed the prostitutes and they said they were picked to go to Papua because they were infected.

I am reminded of methods used to exterminate the native peoples of North America, smallpox, alcohol, etc.

The army even manufactures its own brand of raw alcohol notorious for its methanol toxicity. One morning in Nabire I remember walking along the street and coming across a dead Papuan, dead from drinking the cheap alcohol, I was told. It has been sold everywhere for many years, but now the Papuan governor has introduced a total ban on alcohol. This move might have been inspired by good intentions but will create a thriving black-market dominated by smuggling which will be controlled by the military. Selling logs to China and other places, despite repeated moratoriums on logging, is a business that reaps hundreds of millions of dollars for the army in both provinces, Papua/West Papua. But this is more ecological annihilation.

What did you mean when you used the word genocide?

Let me return to the question of genocide. US Congressman Eni Faleomavaega once asked me to find out more about the killing that took place in the highlands in 1977 – mass killing. The Indonesian army used four Bronco OV10 fighter/bomber planes, ex Vietnam, strafing and bombing non-stop for four months in the highlands. Valley after valley of people working in the gardens tending their sweet-potato crops, villages that had been there for generations – suddenly attacked by the new boss from Jakarta. A Dutch doctor in the highland town of Wamena took note of the number of widows visiting the hospital there the following year and calculated the death toll was above 20,000 people. I have also met Christian missionaries who were in the area when this massive killing spree took place. For one woman, so bad was the horror she was traumatized for the rest of her life. During my first visit to Jayapura in 1978, I recall one night a young boy about 12 years of age came out from under a building, pleading with me: “They kill my mother, they kill my father, and now they kill me.” I had no idea what he was talking about: only later I found out what had happened in the highlands, from where the child had fled, walking for weeks.

The Dutch doctor also noted that four plain-clothed Americans were acting as advisers for the Indonesian pilots involved in this non-stop bombing and strafing. They were providing advice to the pilots on how best to attain better angles and approaches as they searched for new targets beyond the main Baliem valley. The surrounding region which took only minutes to reach by plane took many hours to reach by road transport. This fertile region was the most densely populated of all areas in the entire territory and Papuan communities had lived there for centuries. This was where Richard Archbold (a former CEO from Standard Oil in pre-war days) landed in his giant flying-boat. He dubbed the place “Shangri-La” because the Papuans were so peaceful – men, women and children working in the fields until 2pm, then the men washing the children in the river before conducting school lessons while the women retired to the village to prepare the evening meal.

Do you have figures on how many people in “Shangri-La” were slaughtered in this genocide?

In a land such as Papua, because of the rugged terrain and remoteness, there is always great difficulty in obtaining accuracy of demographic information. The figure of 100,000 Papuans used to be bandied about as the death toll resulting from Indonesian army repression, over the years; but this was chosen only because the Human Rights group which promoted the figure had that number of names and addresses of people, missing or dead. This included persons who were known to have been dropped by helicopter over the sea, or persons forced into a latrine only to have their head pushed under and held there until death. Two decades ago, I discussed this very issue with prominent Papuan activists and realised, while they knew the figure was much higher, the purpose in claiming the figure of 100,000 was because it was indisputable. To gain a better idea of the total number, however, I checked the population figures available from the last census held before the Dutch departed, and with it I compared the statistics available from eastern New Guinea, populated by Papuans with similar culture but under the former colonial control of Australia. The dividing line between east and West Papua is simply a meridian, 141 degrees East, which was agreed upon by the Dutch in the western half, and in the eastern half British and German (before Australia took control after the First World war.) in places, this dividing line which became a colonial border ran straight through the middle of some villages.

So in Netherlands New Guinea in 1960 there was a census, and in the eastern half called Papua New Guinea (PNG) the Australian administration also conducted a census in 1960. PNG always had more inhabitants than the western half but it was the rate of growth that was crucial because it gave a basis of comparison with the similar Papuan culture in the western half. The rate of growth of the PNG Papuan population from 1960 to 2002 was then calculated. This rate I then applied to the census statistics compiled by the Dutch in 1960, to calculate an estimation of what the population in the western half might be in 2002, or might have been expected to be.

Under Indonesian army rule for four decades, there was a remarkable discrepancy showing a population deficit of 1.3 million Papuans. Of course, we must also include in this rough calculation the exodus of Papuans from west to east once the terror of Indonesian army rule became apparent, but it shows without doubt that a vast number of Papuans went missing. This population deficit in the territory of Indonesian-controlled West New Guinea was calculated when the differentiation between Papuan and non-Papuan was still a feature of the census questions. Nowadays this deficit has been more than filled by people coming to Papua from other Indonesian islands, mainly Java and Sulawesi. These people from outside Papua are referred to as transmigrants and, because the flow has not been restricted, Papuans are now a minority in their own land. The figure of 1.3 million Papuans missing over 40 years of army occupation is comparable to the figure often cited for the Armenian genocide that occurred in Turkey around the time of the First World War, an occurrence that has never been acknowledged by the government of Turkey. The estimate of 1.3 Papuans, and the method used for reaching this number, was in an article I wrote for the Encyclopedia of Genocide published by Macmillan in 2005. Papua, most of these people would have died from disease but this still implicates the role of Indonesia in the population loss. Even today, in some remote areas, Papuans living in isolated regions rarely, if at all, ever see a medical doctor.

Have you traveled to these areas to confirm this?

In 1983, I was sent to visit the territory by the London-based Anti-Slavery International to report on figures released by an American bishop operating in the Asmat region along the southern coastline of West New Guinea (then called Irian Jaya.) The bishop claimed 600 out of 1000 Papuan children under five years of age were dying in that region. I went to check out whether this was true or not: it was true.

The unspoken tragedy here comes from medical reports compiled in Dutch times which described this area as a medical phenomenon because of the absence of disease. A few persons had infections in their feet but otherwise the entire area was free of disease.

Access to the Papuan people started with the New York Agreement in August 1962. Freeport gained access to rich mineral deposits almost immediately and then in 1977 the Indonesian army gained access to the indigenous Papuan highlanders. In cultural terms these two were the complete antithesis of each other and the consequences of this has been devastating: the Papuan population suffered an immense depletion in numbers during the Suharto era and conditions two decades later still have Papuans living in appalling conditions. Access for foreigners into the territory has become less of a problem but still some journalists find themselves on the restricted list. But in Papua the digital age has dawned and Papuans are determined to tell the world their plight. In the same way that Indonesian nationalists informed the world to release themselves from Dutch colonial power, Papuans are doing likewise in the hope that the iron grip of the Indonesian army will be released.

What’s the position of the Jakarta government?

The Jakarta government is faced with a stupendous task of negotiating with the Papuan people – perhaps a process similar to the South African ‘Truth and Reconciliation’ – before any progress can be made. The main problem, from the perspective of one who has observed Papuan-Jakarta relations over the decades, is that Jakarta seems reluctant to admit what the army has done, not just during the Suharto era but also in Papua/West Papua today. There does seem to be an administrative gap between what Jakarta says and what actually happens in terms of army brutality in Papua. Whether or not this gap is diminishing, as it seems to be, remains debatable. During the Suharto era, the army was utterly ruthless but in the post-Suharto era we are told things have changed. This change can be gauged by the discrepancy that now appears between Jakarta announcements and the reality in Papua of life under the army, and the police. The post-Suharto era has police in a more prominent role, of course, but this has often led to full-on gun battles between the army and police, fighting over their business interests in this remote corner of Indonesia.

In the first half of 2016, thousands of Papuans have been arrested for peacefully demonstrating in the street, attempting to voice their concern about their human rights, their culture, their lives.

Army and police- with a few exceptions – enjoy impunity from the Indonesian judicial process. For example, six months ago I heard how two young boys in a remote region in the Papuans highlands had their pig killed by a passing car. Pigs are a valuable commodity, and a fully grown one is worth two or three times the price it would fetch in Australia because the pig is so integrated into the culture… many forms of celebrations, weddings for example, would involve roasting a pig or several pigs for the community, not only for the vital nutrients but as a system of cultural bonding. So the two young boys were stopping cars on the road and asking drivers to pay some money as compensation for the pig they had lost. Rp50,000 (rupiahs) would be the same as $5. Two policeman drove to investigate. As the windows were winding down and the boys were about to ask for some money, the police simply shot both boys. Life in Papua – if you are a Papuan – is precarious.

Thank you, Prof. Poulgrain for this disturbing history lesson on Indonesian and American relations.

Interviewed by Edward Curtin