The Berlin Wall, Fifty Years Ago: Disturbed By Lack of Warning, JFK Asked Intelligence Advisers to Review CIA Performance

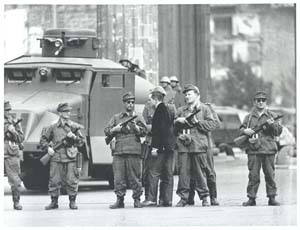

“East German infantrymen line-up in close ranks to seal off Berlin’s key border crossing point, the Brandenberg Gate” [from the USIA caption], undated, circa 13 August 1961. (All photos from National Archives, College Park MD, Still Pictures Division, Records of U.S. Information Agency, RG 306, collection PS-D, box 56)

The Berlin Wall, Fifty Years Ago

While Condemning Wall in Public, U.S. Officials Saw “Long Term Advantage” if Potential Refugees Stayed in East Germany

Three Days Before Wall Went Up, CIA Expected East Germany Would Take “Harsher Measures” to Solve Refugee Crisis

Disturbed By Lack of Warning, JFK Asked Intelligence Advisers to Review CIA Performance

National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 354

Posted – August 12, 2011

For more information contact:

William

Washington, D.C., August 12, 2011 – Fifty years ago, when leaders of the former East Germany (German Democratic Republic) implemented their dramatic decision to seal off East Berlin from the western part of the city, senior Kennedy administration officials publicly condemned them. Nevertheless, those same officials, including Secretary of State Dean Rusk, secretly saw the Wall as potentially contributing to the stability of East Germany and thereby easing the festering crisis over West Berlin. Indeed, U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union Llewellyn Thompson had written that “both we and West Germans consider it to our long-range advantage that potential refugees remain [in] East Germany.” This surprising viewpoint from Thompson and Rusk, among others, is one of a number of points of interest in declassified documents posted today by the National Security Archive.

“Forming a human chain, West Berlin police force hundreds of angry, jeering West Berliners, past the Soviet War Memorial and away from the Brandenberg Gate, 14 August 1961. East German forces held off the surging crow with water cannon before West Berlin police pushed them back to prevent a major incident” [from the USIA caption]

The previously secret documents also reveal new information about one of the remaining unknowns from the period—how well (or poorly) U.S. intelligence agencies carried out their responsibility. In one record, President John F. Kennedy’s frustration shows through over the fact that he did not receive adequate advance warning of the East German move.

Some of the documents posted today were released by the CIA through its CREST database at the National Archives, College Park. As a few of them are heavily excised, the National Security Archive has requested further declassification review. Other relevant documents–CIA daily reports to President Kennedy during the Wall crisis–remain classified because of agency insistence that sources and methods are at risk. The Archive has appealed these denials.

*********

On 13 August 1961, East German security officials imposed harsh controls at the East-West borders in Berlin designed to stop the flow of thousands of refugees, mostly fleeing through West Berlin. Implausibly justifying the measures as a defense against West German aggression, the fundamental concern was the threat of economic disaster for the former German Democratic Republic (GDR). To stop its citizens from escaping, the GDR put up barbed-wire fences which soon turned into concrete barriers. A wall was being constructed (although it became a taboo in the GDR to call it a “Wall” (Note 1)). Declassified documents posted today by the National Security Archive shed light on how U.S. diplomats and intelligence analysts understood the East German refugee crisis and the sector border closings.

For nearly thirty years, the Berlin Wall was the symbol of a tyrannical regime that had virtually imprisoned its population. When the Wall went up, however, the Western Allies with occupation zones in West Berlin—France, the United Kingdom, and the United States–were already at loggerheads with the Soviet Union over the status of West Berlin. Since November 1958, when Khrushchev issued his first ultimatum, many worried that Khrushchev and Ulbricht might sign a peace treaty that could threaten Allied and West German access to West Berlin. (Note 2) For those reasons, key U.S. government officials did not see the Wall as a threat to vital interests; they had even thought it better if potential East German refugees stayed at home. While seeing the sector border closing as a “serious matter,” Secretary of State Dean Rusk probably breathed a sigh of relief when he observed that it “would make a Berlin settlement easier.”

The decision taken in early July 1961 by Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev and East German president Walter Ulbricht to close the border was a deep secret. While no one on the U.S. side predicted a “wall”, diplomats and intelligence analysts saw the possibility of harsh steps to stop the refugee traffic. Nevertheless, East Germany’s draconian moves to close the sector borders came as a surprise to President Kennedy. Declassified documents shed light on what some saw as an intelligence failure or at least a failure by intelligence agencies to warn President Kennedy and his advisers of the possibility of GDR action.

“An East Berliner pleads with members of the East German People’s Police as he tried to cross the closed border between East and West Berlin, 8-14-1961” [from the USIA caption]

Among the other disclosures in this release:

- According to a State Department report, the CIA Station in West Berlin attributed the GDR refugee crisis to the larger crisis over West Berlin. East German citizens worried that if Khrushchev and Ulbricht signed a treaty separating East from West Berlin, their “last chance to escape” would end.

- State Department officials recommended that if the East Germans and the Soviets took severe action to halt the flow of refugees, Washington should protest and “advertise it to the world,” but avoid any action that exacerbated the problem. A revolt in East Germany was not in the U.S. interests “at this time.”

- During the weeks before the Wall crisis, U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union Llewellyn Thompson observed rather pitilessly that “except for the danger of building up pressure for explosion [in the GDR] both we and West Germans consider it to our long-range advantage that potential refugees remain [in] East Germany.” The implication was that the refugee crisis was destabilizing East Germany and that if East Germans stayed home this could ease Soviet pressure on West Berlin.

- Officials at the U.S. mission in West Berlin reported on 7 August that if the daily rate (during July 1961) of over 1,100 refugees continued, it would have an “unquestionably disastrous” impact on the GDR economy. East German security police were already removing from trains to East Berlin “almost all males between the ages of 12 and 35.”

- The CIA’s Office of Current Intelligence reported on 10 August that the regime is considering “harsher measures to reduce the flow” of refugees, although it did not list any possibilities.

- In a speech on 10 August, Ulbricht declared that “We have discussed the (refugee) matter with our Soviet friends and with representatives of the Warsaw Pact states and we have agreed that the time has come when one must say ‘so far and no further.'” Several months later, the U.S. President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board (PFIAB) saw this statement as the “best indicator” that action was about to take place.

- Washington and other Allied governments did not take significant countermeasures against the sector border closings because basic allied rights were not at stake. Secretary of State Dean Rusk expressed prevailing sentiment when he declared that the wall was not a “shooting issue.”

- Allied inaction and the shock of the border closing caused a significant morale problem in Germany, especially West Berlin, which the Kennedy administration tried to remedy. Within a few days, a U.S. Army combat brigade arrived in West Berlin and so did Vice President Lyndon Johnson.

- President Kennedy’s feeling that he was not adequately warned about the imminent of East German action to close down the sector borders led him to ask the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board for a report on what “advance information” the intelligence agencies had.” According to PFIAB, intelligence agencies had not provided top policymakers with “adequate and timely appraisals of the advance information which had been collected.”

-

A year after the Wall went up, State Department officials learned from British diplomats that Soviet Deputy Premier Mikoyan had agreed with British Labor Party Leader Harold Wilson’s statement that the Wall was a “scandal and a blot on Communism.”

As noted, one of the few remaining puzzles about the U.S. reaction to the Wall concerns the performance of U.S. intelligence during the lead-up to the sector border closing. The CIA provided Kennedy with a daily report, the “President’s Intelligence Checklist” [PICL] (the forerunner to the President’s Daily Brief), but what it had sent Kennedy during the previous several days remains a secret. So far the CIA has refused to declassify any of the PICLS produced during 10-14 August 1961 (and a PFIAB report on the CIA’s conduct remains heavily excised). But the National Security Archive’s mandatory review appeal for the PICLS is before the Interagency Security Classification Appeals Panel which may decide that CIA secrecy claims are inflated and declassify information.

Read the Documents

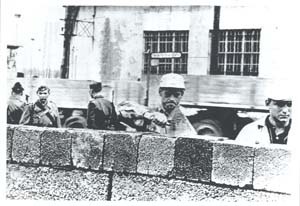

Monitored by East German police, a mason builds a concrete wall at the sector border, mid-August 1961. East Berliner pleads with members of the East German People’s Police as he tried to cross the closed border between East and West Berlin, 8-14-1961

Document 1: John C. Ausland, Berlin Desk, Office of German Affairs, to Mr. Hillenbrand, “Discontent in East Germany,” 18 July 1961, Secret

Source: William Burr, ed., The Berlin Crisis 1958-1062 (Digital National Security Archive)

With thousands of refugees fleeing East Germany, mostly through West Berlin–more than 100,000 during January-June 1961–Ulbricht importuned Khrushchev to let him close the sector borders at the East-West line in Berlin. The Soviets understood that such action would have a adverse impact on East and West German opinion, but, as Hope Harrison has shown, in early July 1961 Khrushchev secretly approved Ulbricht’s request. (Note 3)

The Khrushchev-Ulbricht decision was closely held, but the options available to Communist leaders could be deduced. Looking closely at developments in East Germany, John C. Ausland saw a highly unstable situation, with the refugee flow stemming directly, according to the CIA, from Moscow’s tough policy on West Berlin: What inspired East Germans to flee was their apprehension that if the Soviets signed a treaty with the GDR, a “last chance to escape” would end. While the odds for an internal revolt in East Germany were low at the moment, if the Ulbricht regime took harsh measures to stop the flow of refugees, a “deep deterioration” and a domestic explosion could transpire.

Ausland commented on a recent comment by U.S. Ambassador to West Germany John Dowling that if another revolt in East Germany broke out, the United States should not “stay on the sidelines” as it had during the 1953 uprising. (Note 4) Noting that the U.S. did not want to see another revolt in East Germany as in 1953 at “this time,” Ausland also argued that Washington did it want to exacerbate the situation. He may have been concerned about the anticipated violence of Soviet and East German repression and the risk that an uprising in East Germany could lead to wider conflict, even East-West warfare, in Central Europe. Yet if Moscow and East Berlin took action to halt the flow of refugees, Washington should “help advertise it to the world.” The U.S. could consider economic countermeasures if the GDR clamped down on the borders to stop refugees.

Document 2: State Department cable to Bonn Embassy, 22 July 1961, Secret

Source: The Berlin Crisis

In a cable drafted by Ausland and summarizing the analysis in his memorandum, the State Department informed U.S. diplomats in Bonn that, in light of the refugee flow, two possibilities existed: East German action to tighten control of the movement of people between East and West Berlin or serious economic problems leading to “serious disorders.” While the Soviets wanted to reach a settlement on the West Berlin problem, they were sitting on “top of a volcano” and would support “restrictive measures” if the flow of refugees continued. In the short term, however, the Department estimated that the Soviets would “tolerate” the refugee problem while pressing for a Berlin situation, unless the refugee problem worsened. The U.S. would benefit from some social instability in East Germany because it could force the Soviets to relax pressure on West Berlin, but “we would not like to see revolt at this time.”

Document 3: West Berlin mission cable 87 to State Department, 24 July 1961

Source: John F. Kennedy Presidential Library, National Security Files, box 91, Germany, Berlin, Cables 7/16/61-7/25/61

Responding to the Department’s cable (document 2) on the East German refugee crisis, West Berlin mission chief Allen Lightner did not pick up on the State Department’s references to the possibility of security measures to close the sector borders. Instead, he suggested that continued refugee flow or adverse East German internal reaction to an East German-Soviet peace treaty might hold back Khrushchev from initiating a “showdown” over West Berlin. Believing that more was needed than “advertising the facts,” Lightner suggested “intensifying doubts and fears” among Soviet leaders about the possibility of an East German uprising through a program of overt and covert political and diplomatic operations. Noting that so far West Germany had not encouraged refugees to head West, but had actually discouraged them (possibly to minimize East-West tensions and perhaps to minimize the costs of absorbing the refugees), Lightner suggested that Bonn and Washington could threaten to reverse that policy.

Document 4: Moscow Embassy Cable 258 to Department of State, July 24, 1961, Secret,

Source: RG 59, Decimal Files 1960-1963, 762.00/7-2461 (from microfilm)

Commenting on the State Department cable (document 2), Ambassador Thompson argued that one of the chief Soviet objectives in the Berlin crisis was the “cessation of refugee flow” from East Germany. Noting that both Washington and Bonn believed it “to our long-range advantage that potential refugees remain in East Germany” (probably to reduce Soviet pressure on West Berlin), Thompson nevertheless conceded that unilateral GDR action would have “many advantages for us” by demonstrating the weaknesses of the Soviet and East German position. He advised against giving the impression that Washington would take “strong countermeasures” if the GDR “closed the hatch” to avoid possible threats to Western access to Berlin.

Document 5: West Berlin mission cable 127 to State Department, 2 August 1961

Source: RG 59, Decimal Files 1960-1963, 762.00/7-2461 (from microfilm)

The Berlin mission cited report on a growing number of “border crossers”–East Berliners who had day jobs in West Berlin–among the refugees but the West Berlin Senate was not sure whether a “trend” had begun or not. It was also not clear whether the East Germans had begun a targeted crack-down on the “border-crossers” although there were reports of an “intimidation campaign.”

“West Berlin mayor Willy Brandt welcomes Colonel Glover S. Johns. Jr. Commanding Officer of the1st Battle Group, 18th U.S. Infantry, as the unit arrived in the city 8-20-1961 to reinforce the defense garrison there. At center is Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, who was in Germany as personal representative of the President of the United States. The troops came to West Berlin via the autobahn corridor across East Germany” [from the USIA caption]

Document 6: Bonn Embassy Airgram A-135 to State Department, 3 August 1961, Limited Official Use

Source: The Berlin Crisis

On July 30, 1961, Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee Sen. J. William Fulbright (D-Ark) made a television statement suggesting that closing the Berlin escape hatch could be a subject for negotiations over West Berlin. He said further that the “truth of the matter is that …the Russians have the power to close it in any case. I mean you are not giving up very much because I believe that next week if they chose to close their borders, they could without violating any treaty.” Further, the East Germans “have a right to close their borders.” (Note 5) As the U.S. Embassy in Bonn reported, Fulbright’s comments created a furor in West Germany and West Berlin. For example, at first West Berlin Mayor Willy Brandt could not believe that Fulbright had said it. Certainly, East German and Soviet authorities must have seen it as a signal that the West would tolerate the closing of the sector borders.

Document 7: West Berlin Mission Despatch 72 to State Department, “Soviet Zone of Germany – Refugees, Border Crossers (Grenzaengers), East German Police Controls, and Recent East German Legal-Judicial Actions,” 7 August 1961, Official Use Only

Source: The Berlin Crisis

The U.S. mission in West Berlin provided a full account of the ins and outs of the “second Berlin access problem,” the right of entry into West Berlin of the 16 million residents of East Germany and East Berlin. While the “first Berlin access problem”—Allied and West German access to West Berlin—was in a “pre-crisis” or “potential crisis stage,” the “second access problem” was “nearer to a ‘crisis’ stage as a result of recent repressive actions by the Soviet Zone regime.” With over 1,100 refugees arriving in West Berlin and West Germany daily, a rate which had “unquestionably disastrous” implications for GDR, East German security police were tightening up controls on roads, railroads, commuter trains, and the Berlin subway. Receiving close scrutiny by police and courts were younger men and “border crossers,” East Berliners who worked in West Berlin and were fleeing in larger numbers. Sent by diplomatic pouch, this report did not reach the State Department Berlin Desk until 14 August, the day after the sector border closing.

.

Document 8: “Daily Brief” and “East German Security Measures Against the Refugees,” Central Intelligence Bulletin, 9 August 1961, Top Secret, Excised copy

Source: CIA Research Tool (CREST), National Archives II

While “morale” in West Berlin was fluctuating, partly because of apprehension about possible Western diplomatic compromises with Moscow, refugees were entering the West in record numbers. The East German government was “faced with the dilemma that actions necessary to halt the refugee flow would in all likelihood cause a sharp and dangerous rise in popular discontent.” So far refraining from adopting “special internal security measures,” the regime was using normal police controls and propaganda techniques to “stem the flow.” The most coercive measure taken so far was forcing “border crossers” to register with GDR authorities, an action that had also been coordinated with the Soviets. (Note 6)

Document 9: Memorandum of conversation, “Secretary’s Meeting with European Ambassadors,” Paris, 9 August 1961, Secret

Source: State Department Freedom of Information Act release to National Security Archive

While in Paris for meetings with French, British and West German foreign ministers, Secretary of State Dean Rusk and other senior officials held a lengthy discussion with U.S. ambassadors on the Berlin crisis and its implications. The East German refugee problem did not get a mention, which suggests its low salience for the Kennedy administration’s Berlin policy. As Rusk emphasized it was important to “draw a line between what was vital to our interests and [what was] important but not worth risking the precipitation of armed conflict.” As Kennedy had stressed in a televised address on 24 July, Rusk argued that what was vital was “the Western presence in West Berlin” and “our physical access to the city.” Rusk was hopeful that the Soviets did not intend to threaten those interests and would be amenable to negotiations over non-vital interests. A “peaceful settlement” was essential because in the nuclear age, war could no “longer be a deliberate instrument of national policy.”

Document 10: “The East German Refugees,” Office of Current Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency, 10 August 1961, excised copy [full version undergoing declassification review at request of National Security Archive)

Source: CREST

As the refugee crisis intensified, the CIA’s Office of Current Intelligence prepared a fairly detailed analysis, including numbers of refugees, their motives, the impact on East Germany, countermeasures, and the effect on Ulbricht and Khrushchev. The volume of refugees was the highest since the crisis year of 1953 and as already noted, fear that the Soviets would sign a treaty with the GDR affecting the status of West Berlin provided a significant motivation to flee. The report cited “evidence that the regime is considering harsher measures to reduce the flow” but the evidence is excised from this release except for a reference to decrees that would soon be emanating from the East German Peoples Chamber. Most likely this report went to middle-level officials at other intelligence agencies, the State Department, and the Pentagon. While the CIA could not predict when or how the GDR would act, anyone who read it could not have been too surprised by what took place a few days later. (Note 7)

Document 11: “Daily Brief and “Marshall Konev,” Central Intelligence Bulletin, 11 August 1961, Top Secret, Excised copy, excerpts

Source: CREST

On 9 August, over 1,600 refugees from East Germany and East Berlin registered at the refugee reception center at Marienfelde. The appointment of the former Warsaw Pact commander, Marshall Ivan Konev, as commander of Soviet forces in East Germany was a sign of Khrushchev’s “efforts to impress the West with his determination to conclude a German treaty before the end of this year.”

Document 12: West Berlin mission cable 176 to State Department, 13 August 1961, Confidential

Source: The Berlin Crisis

Early in the morning of 13 August 1961, the East German regime enacted decrees mandating “drastic control measures” at the sector borders to prevent East Germans from going into West Berlin. The East Germans had planned to take this action early on a Sunday morning to catch East and West Berliners by surprise, when most were distracted by weekend holiday plans or were otherwise not up and about. (Note 8) Panic in East Berlin and shock in West Berlin and elsewhere quickly followed the border closing.

Mission chief Allen Lightner speculated that the decision may have been taken at a recent Warsaw Pact meeting in Moscow, a view that would soon be held by many scholars. As Hope Harrison has demonstrated, the basic decision had already been taken but the Warsaw Pact meeting during 3-5 August was important for consensus-building purposes in the Eastern bloc, but also as a deterrent so that the West did not see the GDR action as “only its plan.” (Note 9)

Document 13: West Berlin mission cable 186 to State Department, 13 August 1961, Confidential

Source: The Berlin Crisis

The mission provided the State Department with an update of the controls over the East German population. Subway cars heading into the West failed to show up and control measures were being implemented “everywhere” with East German police stringing up barbed wire at border points. The flow of refugees had not stopped entirely, because people were fleeing through the canals and fields. The mission interpreted Soviet troop deployments on the periphery of Berlin as a “show of strength” to “intimidate” East Berliners and disabuse them of any notion of initiating resistance as in 1953. So far East German officials had not interfered with the movement of Western observers.

Document 14: State Department cable 340 to Embassy Bonn, 13 August 1961, unclassified

Source: The Berlin Crisis

Secretary of Dean Rusk quickly issued a statement condemning the sector border closings as a “flagrant violation of the right of free circulation throughout the city.” “Communist authorities are now denying the right of individuals to elect a world of free choice rather than a world of coercion.” Rusk noted that the actions taken by the East Germans violated Berlin’s four power status but they were not aimed at “the allied position in West Berlin or access thereto.” That is, they did not touch on the “vital interests” which Rusk had discussed with U.S. diplomats on 9 August. A few days later, during a meeting of the Berlin Steering Group, Rusk underlined the point when he observed that the sector border closing was a “non-shooting” issue. At the same time, he speculated that the Berlin Wall might help solve the crisis, implying that a more stable GDR might make the Soviets more relaxed about the West Berlin problem (see document 21 at page 86). Nevertheless, serious tensions over West Berlin persisted during the months that followed. (Note 10)

Document 15: Analysis by Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Current Intelligence, cable to White House/Hyannis[port], circa 13-14 August 1961, Secret

Source: CIA FOIA Web site

The CIA kept the White House informed of current developments in Berlin with memoranda like this, but President Kennedy was not satisfied that he had been given adequate warning of the possibility of imminent GDR action to close the sector borders. Apparently, when the news reached Kennedy at Hyannisport at about 1 p.m., he reacted with some irritation, “How come we didn’t know anything about this?” (Note 11) As noted earlier, what the CIA had reported to President Kennedy in the PICL during the days before the Wall Crisis remains classified.

Document 16: Central Intelligence Agency, “Berlin Situation Report (As of 1630 Hours),” 15 August 1961, excised copy

Source: CIA Research Tool (CREST), National Archives II

CIA had conflicting reports, but the indications were that the East Germans had extended the crackdown to West Berliners and West Germans, who now would be required to get a permit if they wished to enter (or drive into) East Berlin.

Document 17: “Conclusion of Special USIB [U.S. Intelligence Board] Subcommittee on Berlin Situation,”

Central Intelligence Bulletin, 16 August 1961, Top Secret, Excised copy, excerpts

Source: CREST

The USIB Subcommittee believed that a “critical stage” had been reached that could lead to “severe local demonstrations,” but downplayed the possibility of an uprising: “In contrast to the situation in June 1953, the regime has taken the initiative” and has made “an all-out effort to intimidate the population.”

Document 18: Bonn Embassy cable 354 to State Department, 17 August 1961, Secret

Source: The Berlin Crisis

Assessing the German reaction to the sector border closing, Ambassador Dowling was not overly concerned about the situation in West Germany, but he did see a “crisis of confidence” in West Berlin. Washington needed to take “dramatic steps” steps to improve the “psychological climate” there. Martin Hillenbrand, director of the Office of German Affairs later observed that “the volatility of Berlin sentiment, either in the direction of courage or panic, has frequently caught the Western powers by surprise, and this was to provide another good example.” (Note 12)

Document 19: Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Current Intelligence, “Current Intelligence Weekly Summary,” 17 August 1961, Secret, excised and incomplete copy

Source: The Berlin Crisis

This report summarized the status of border controls, refugee movements, communications, Soviet and Eastern bloc positions, and reactions in West Berlin and West Germany. The report refers to concerns about a “crisis of confidence” in West Berlin, where the population is becoming “increasingly restive over the lack of prompt Western countermeasures.”` The unrest depicted in photo 2 conveys some of the agitation.

Document 20: Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Current Intelligence, “Current Intelligence Weekly Summary,” 24 August 1961, Secret, excised copy, excerpts

Source: CREST

This CIA report provides an update on the new GDR controls at the sector border, the construction of concrete barriers to replace barbed-wire fences, tightened regulation of passage by West Berliners and West Germans into East Berlin, interference with Allied military traffic into the East, and security measures. Despite the controls, “significant” numbers were still escaping from the East. The morale problem cited in earlier reports and cables had become less severe owing to the deployment of a U.S. Army battle group and a visit by Vice President Lyndon Johnson. While the Soviets had protested the visits by Johnson and Chancellor Adenauer and accused the West of “provocative” activities” in Berlin, they “sought to minimize the prospect of an imminent crisis,” by playing down immediate threats to Western access to the city.

Document 21: Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Current Intelligence, “Current Intelligence Weekly Summary,” 31 August 1961, Secret, excised copy, excerpts

Source: CREST

According to the CIA, Moscow’s decision to resume nuclear testing suggested that Khrushchev had resorted to “nuclear intimidation” to offset his weakened bargaining position in the Berlin crisis. The sector border closing “severely damaged their efforts to present the East German regime as a sovereign and respectable negotiating partner.” The situation in West Berlin remained difficult; whatever positive impact Vice President Johnson’s visit had on morale had been weakened by East German threats against Western air access to West Berlin. “[A] feeling of frustration and hopeless is already beginning to spread through the West Berlin population.”

Document 22: Executive Secretary, U.S. Intelligence Board, “Review of Advance Intelligence Pertaining to the Berlin Wall and Syrian Coup Incidents,” 12 February 1962, enclosing memorandum from McGeorge Bundy to Director of Central Intelligence, 22 January 1962, with report by President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, Top Secret, excised copy (full version undergoing declassification review at request of National Security Archive)

Source: CREST

President Kennedy’s feeling that he was not adequately warned about the imminent East German action and a coup in Syria on 28 September led him to ask the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board (PFIAB) for a report on what “advance information” the intelligence agencies had before the events and “what lessons might be learned.” According to PFIAB, in both incidents “indications of imminent significant developments were apparently lost sight of in the mass of intelligence reports.” With respect to Berlin, no one knew when the “Berlin Wall” was going up, but “our intelligence collectors did obtain information which pointed to the possible imminence of drastic action by the East German regime.” The problem was the intelligence agencies had not provided top policymakers with “adequate and timely appraisals of the advance information which had been collected.” Case studies of the incidents are heavily excised, but PFIAB declared that a comment by Ulbricht in a public speech on 10 August was the “best indicator” of imminent action. It would be interesting to know how the CIA responded to the PFIAB appraisal, but such information is not available.

Document 23: State Department cable 430 to Bonn Embassy, 14 August 1962, Secret

Source: National Archives, Record Group 59, State Department Decimal Files, 1960-1963, 641.61/8-1462

About a year after the Wall started going up, British Labor Party leader, and future Prime Minister, Harold Wilson met with Soviet Deputy Premier Anastas Mikoyan. According to British diplomats in Washington, Wilson began the conversation by asking “whether Mikoyan did not think Wall was a scandal and blot on Communism.” Mikoyan agreed but “said Wall was necessary to prevent clashes between two halves of Berlin.” This is probably a reference to Soviet claims about provocative actions by West Berlin around the time the sector borders were closed. In any event, Mikoyan assured Wilson that Moscow was keeping a “tight hold on Ulbricht and would not let matters go out of hand.”

Document 24: U.S Department of State, Historical Studies Division, Crisis over Berlin: American Policy concerning the Soviet Threats to Berlin, November 1958-December 1962; Part VI: Deepening Crisis over Berlin–Communist Challenges and Western Responses, June-September 1961, April 1970, Top Secret, Excerpts

Source: Berlin Crisis

During the late 1960s, Department of State historians produced a major study of the 1958-1962 Berlin Crisis, although they did not get the opportunity to complete it. This excerpt provides a useful overview of the refugee crisis and the Kennedy administration’s policy response, including countermeasures and steps to raise morale in West Berlin. Many of the documents cited and summarized were later published in the Department’s Foreign Relations of the United States volumes on the Berlin Crisis.

Notes

1. Patrick Major, Behind the Berlin Wall: East Germany and the Frontiers of Power (Oxford,: Oxford University Press, 2010), 143. The official term was “Anti-Fascist Defense Rampart” or antifaschistischer Shutzwall).

2. For recent accounts of the 1961 crisis, see Frederick Kempe, Berlin 1961: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and the Most Dangerous Place on Earth ( G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 2011); Pertti Ahonen. Death at the Berlin Wall (Oxford : Oxford University Press, 2011); W.R. Smyser, Kennedy and the Berlin Wall : “a hell of a lot better than a war” (Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2009), and Patrick Major, Behind the Berlin Wall: East Germany and the Frontiers of Power. For an influential study of East German-Soviet relations during the 1950s through the Berlin crisis, see Hope Harrison, Driving the Soviets Up the Wall: Soviet-East German Relations,1953-1961 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003),

3. Harrison, Driving the Soviets Up the Wall. 184-187.

4. For a full account of the 1953 East German revolt, see Christian F. Ostermann, Uprising in East Germany 1953: The Cold War, the German Question, and the First Major Upheaval behind the Iron Curtain (Budapest; New York : Central European University Press, 2001).

5. “Senator’s Remarks on TV, “The New York Times, 3 August 1961.

6. Harrison, Driving the Soviets Up the Wall, 188-189. 7. Apparently a few intelligence officers in West Berlin predicted a “Wall”. See Peter Wyden, Wall: Inside Story of Divided Berlin (New York: Simon & Shuster, 1989), at 91-93.

8. Ibid.,189.

9. Ibid., 192.

10. See for example, Lawrence Freedman, Kennedy’s Wars: Berlin, Cuba, Laos, and Vietnam (New York: Oxford, 2000), 79-91, and Smyser, Kennedy and the Berlin Wall.

11. Peter Wyden, Wall: Inside Story of Divided Berlin (New York: Simon & Shuster, 1989), 26.

12. Martin Hillenbrand, Fragments of Our Time: Memoirs of a Diplomat (Athens: University of Georgia, 1998), 190.