Targeting the USSR in August 1945

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Visit and follow us on Instagram at @globalresearch_crg and Twitter at @crglobalization.

***

.

Introductory Note

This article first published in April 2012 focusses on the “Special Relationship” between the US and the USSR. It is of utmost relevance to unfolding events in Ukraine.

While the US and the Soviet Union were allies during WWII, Prof. Alex Wellerstein documents U.S. “war preparations” against the USSR which took place in August 1945 “before the war was officially over”.

And then what happened:

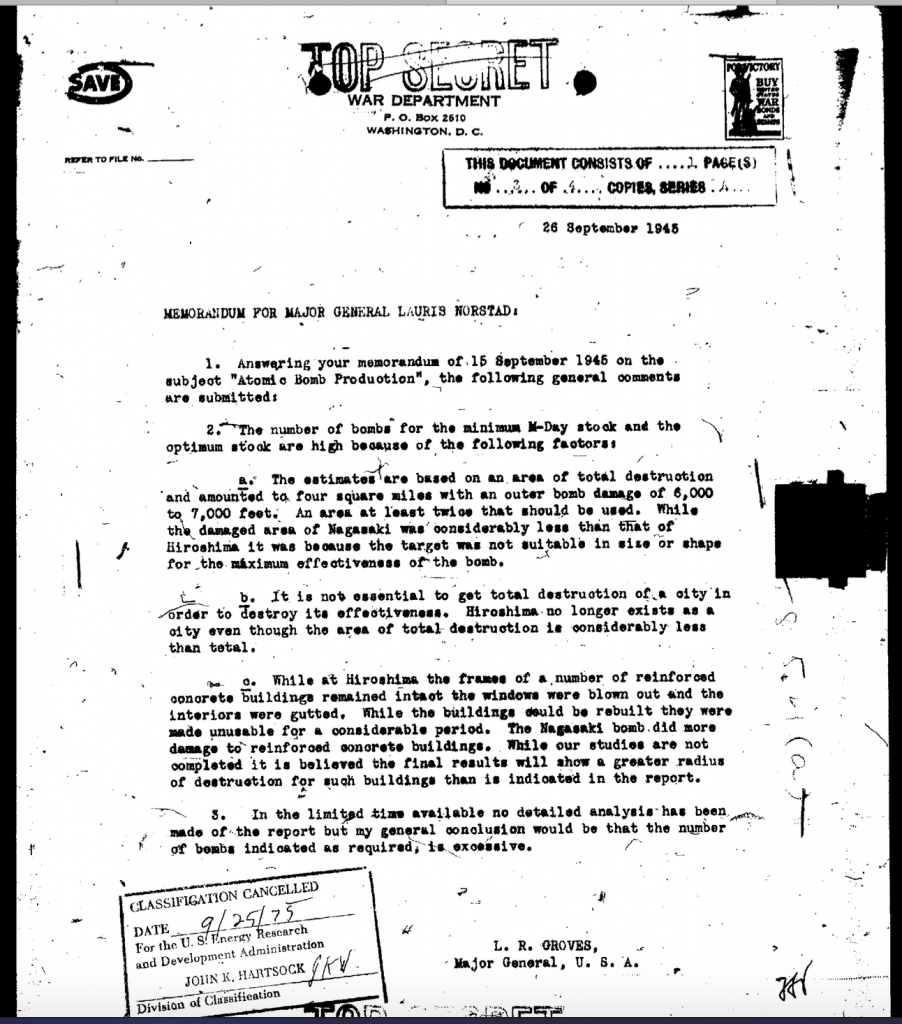

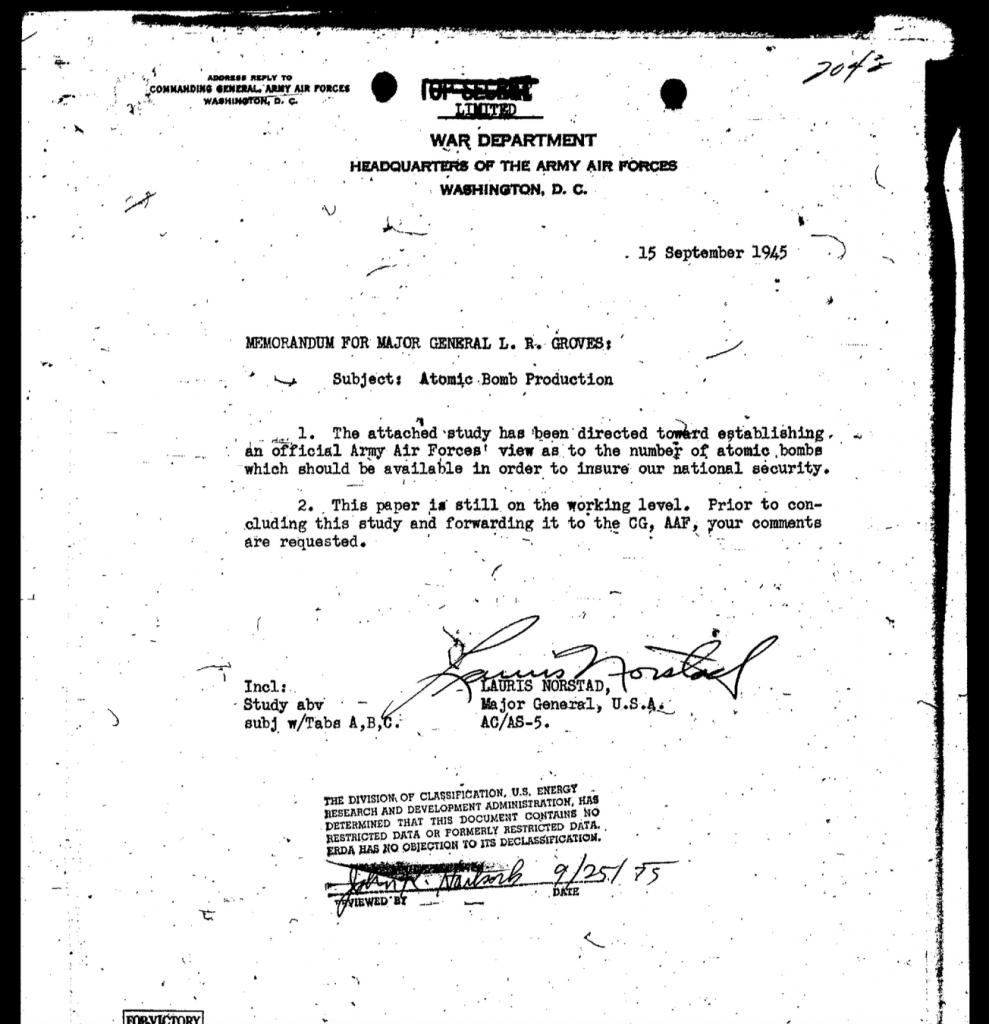

The formulation of a diabolical project released by the War Department (declassified) on September 15, 1945 which consisted in dropping atomic bombs on major cities of the Soviet Union.

According to this secret (declassified) document, “the Pentagon had envisaged blowing up the Soviet Union with a coordinated nuclear attack directed against major urban areas.

All major cities of the Soviet Union were included in the list of 66 “strategic” targets. The irony is that this plan was released by the War Department prior to onset of the Cold War.

Access all the documents of the September 15, 1945 Operation here

Michel Chossudovsky, Global Research, March 13, 2022

Targeting the USSR in August 1945

by Prof. Alex Wellerstein

If the World War II alliance between the United States and the United Kingdom was the special relationship, what was the alliance between the United States and the Soviet Union? The especially problematic relationship? The relationship that could really have used to go to counseling? A relationship forged out of extreme crisis that later seemed like a sketchy thing? (Easily abbreviated as the sketchy relationship, of course.) My wife suggests perhaps calling it the shotgun marriage.

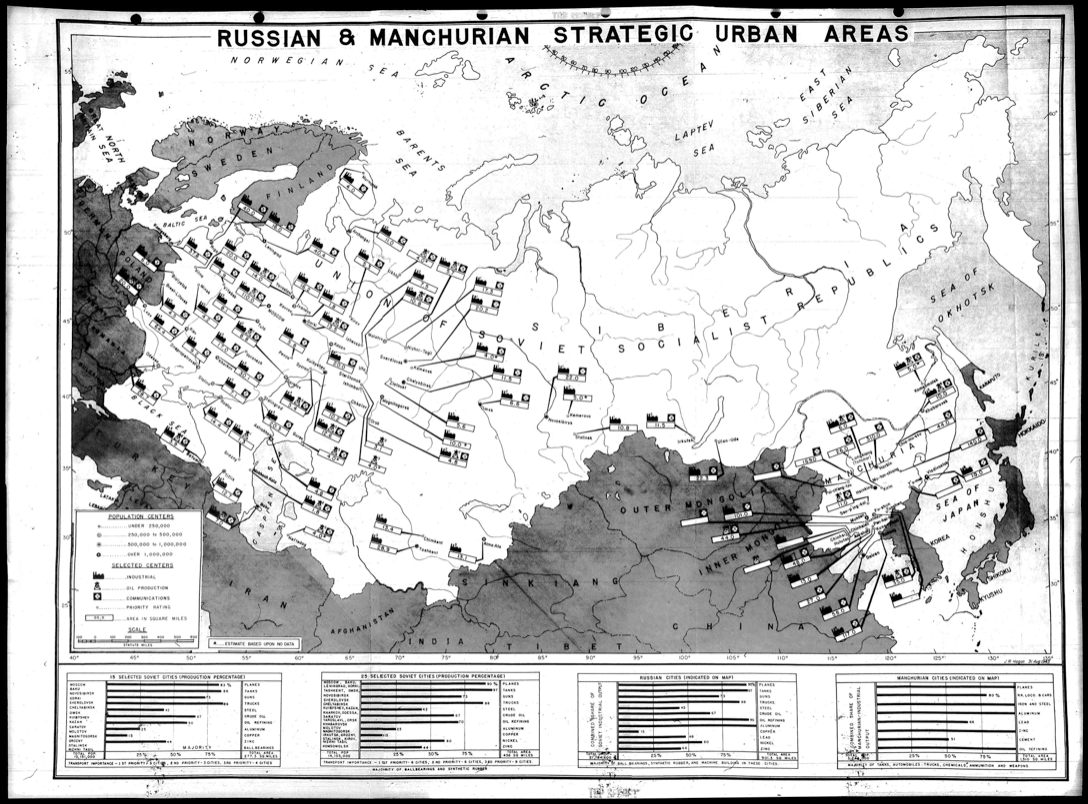

Maybe special fits the bill there too, in the sense of it being odd. Case in point: by August 30, 1945 — before World War II was officially over — some part of the U.S. military force (I’m not sure what branch; the Army Air Corps are a likely suspect) had already taken the time to draw up a list of good targets for atomic bombs in the USSR… and even overlaid a map of the Soviet Union with the ranges of nuclear-capable bombers, along with “first” and “second” priority targets marked on it.1

How many other war alliances end with one side explicitly plotting to nuke the heck out of the other ally? Probably not too many.

This amazing map comes from General Groves’ files, and was sent to him in September 1945 as part of a list of estimates for how many atomic bombs Curtis LeMay thought the US ought to have. I’ll talk about that another time, but here’s a hint: it was so many that even General Groves thought it was too many. Whoa.

A few things: the majority of these “dark” plots are B-29s (the same bombers that carried Fat Man and Little Boy), and they are going out of all kinds of “allied” bases (some currently in their possession, others labeled as “possible springboards”) around the USSR (Stavanger, Bremen, Foggia, Crete, Dhahran, Lahore, Okinawa, Shimushiru, Adak, and Nome). Which is an interesting way to quickly conceptualize the Cold War world from a military standpoint.

The very large, empty plots are for B-36s, which didn’t exist yet. They wouldn’t get fielded until 1949, but were already in the planning stages during the war. The actual B-36s as delivered had somewhat longer ranges (6,000 miles or so, total, if Wikipedia is to believed) than the ones estimated on here.

The target cities are a bit hard to make out (the next time I’m at NARA, I’ll try to get them to bring me the original map), but the “first priority” cities include Moscow, Sverdlovsk, Omsk, Novosibirsk, Stalinsk, Chelyabinsk, Magnitogorsk, Kazan, Molotov, and Gorki. Leningrad appears to be listed as a “second priority” target, which surprises me, but it might just be the microfilm being hard to read. All in all, it’s not the most interesting list of cities: they have literally just taken a list of the top cities in the USSR (based on population, industry, war relevance) and made those their atomic targets.

Stalin has a well-deserved reputation as a paranoid guy. But, as the old saying goes, just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they’re not after you.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram, @globalresearch_crg and Twitter at @crglobalization. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums, etc.

Alex Wellerstein is a historian of science and nuclear weapons and a professor at the Stevens Institute of Technology. He is also the creator of the NUKEMAP.This blog began in 2011. For more, follow @wellerstein.

Notes

1. Citation: “A Strategic Chart of Certain Russian and Manchurian Urban Areas [Project No. 2532],” (30 August 1945), Correspondence (“Top Secret”) of the Manhattan Engineer District, 1942-1946, microfilm publication M1109 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1980), Roll 1, Target 4, Folder 3, “Stockpile, Storage, and Military Characteristics.” The microfilm image I had of this came in two frames, a top and a bottom, and I pasted them together in Photoshop. This took a little bit of warping of the bottom image in odd ways (using Photoshop’s crazy “Puppet Warp” tool) because it didn’t quite line up with the top one due to folds in the paper and things like that. So there is a tiny bit of manipulation here, though none of it affects the content.

Restricted Data

Restricted Data

The History of Nuclear Secrecy in the United States

By Alex Wellerstein

ISBN: 9780226020419

The first full history of US nuclear secrecy, from its origins in the late 1930s to our post–Cold War present.

The American atomic bomb was born in secrecy. From the moment scientists first conceived of its possibility to the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and beyond, there were efforts to control the spread of nuclear information and the newly discovered scientific facts that made such powerful weapons possible. The totalizing scientific secrecy that the atomic bomb appeared to demand was new, unusual, and very nearly unprecedented. It was foreign to American science and American democracy—and potentially incompatible with both. From the beginning, this secrecy was controversial, and it was always contested. The atomic bomb was not merely the application of science to war, but the result of decades of investment in scientific education, infrastructure, and global collaboration. If secrecy became the norm, how would science survive?

Drawing on troves of declassified files, including records released by the government for the first time through the author’s efforts, Restricted Data traces the complex evolution of the US nuclear secrecy regime from the first whisper of the atomic bomb through the mounting tensions of the Cold War and into the early twenty-first century. A compelling history of powerful ideas at war, it tells a story that feels distinctly American: rich, sprawling, and built on the conflict between high-minded idealism and ugly, fearful power.