Syria and the Project to Balkanize the Middle East

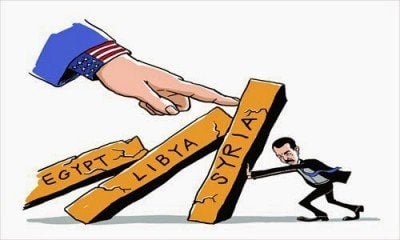

A decade ago I published a book, Israel and the Clash of Civilisations, that examined Israel’s desire to Balkanize the Middle East, using methods it had refined over many decades in the occupied Palestinian territories. The goal was to unleash anarchy across much of the region, destabilising key enemy states: Iran, Iraq, Syria and Lebanon.

The book further noted how Israel’s strategy had influenced the neoconservative agenda in Washington that found favour under George Bush’s administration. The neocons’ destabilisation campaign started in Iraq, with consequences that are only too apparent today.

My book was published when efforts by Israel and the neocons to move the Balkanisation campaign forward into Iran, Syria and Lebanon were stumbling, and before it was clear that other actors, such as ISIS, would emerge out of the mayhem. But I predicted – correctly – that Israel and the neocons would continue to push for more destabilisation, targeting Syria next, with disastrous consequences.

Today, Israel’s vision of the region is shared by other key actors, including Saudi Arabia, the Gulf states, and Turkey. The current arena for destabilisation, as I predicted, is Syria. But if successful, the Balkanisation process will undoubtedly move on and intensify against Lebanon and Iran.

Although commentators tend to focus on the “evil monsters” who lead the states targeted for destruction, it is worth remembering that before their disintegration most were also oases of secularism in a region dominated by medieval sectarian ideologies, whether the Wahhabism of Saudi Arabia or the Orthodox Judaism of Israel.

Syria’s Bashar Assad, Iraq’s Saddam Hussein and Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi are or were ruthless and brutal in the way all dictators are, against opponents who threaten the regime. But before their states were targeted for “intervention”, they also oversaw societies in which there were high levels of education and literacy, well-established welfare states, and low levels of sectarianism. These were not insignificant achievements (even if they are largely overlooked now) – achievements that large sections of their populations appreciated, even more so when they were destroyed through outside intervention.

These achievements were not unrelated to the fact that the regimes were or are more independent of the US than the US and Israel desire. The rulers of these states, which comprise disparate sectarian groups, had an interest in maintaining internal stability through a carrot and stick approach: benefits for those who submitted to the regime, and repression for those who resisted. They also made strong alliances with similar regimes to limit moves by Israel and the US to dominate the region. Balkanisation has been a powerful way to isolate and weaken them, so the process can be expanded to other renegade states.

This is not to excuse human rights violations by dictatorial regimes. But it is to concentrate on an even more important issue. What we have seen unfolding over the past 15 years is part of a lengthy process – often described in the West as a “war on terror” – that is not designed to “liberate” or “democratise” Middle Eastern states. If that were the case, Saudi Arabia would have been the first state targeted for “intervention”.

Rather, the “war on terror” is part of efforts to violently break apart states that reject US-Israeli hegemony in the region, so as to maintain US control over the region’s resources in an age of diminishing access to cheap oil.

Although it is tempting to prioritise human rights as the yardstick for which sides we prefer, by now there should be little doubt that the conflicts unfolding in the Middle East are not about the promotion of rights.

Syria offers all the clues we need.

The agents trying to overthrow Assad in Syria are no longer civil society groups and democracy activists. They were too small in number and too weak to bring about change or threaten the Assad regime. Instead, whatever civil war there may initially have been has transformed into a proxy war. (In a closed society like Syria, it is of course almost impossible to know what drove the initial opposition – was it a fight for greater human rights, or growing dissatisfaction with the regime concerning other issues, such as food shortages and population displacements that were themselves a consequence of long-term processes triggered by climate change?)

A coalition of the US, Saudi Arabia, the Gulf states, Turkey and Israel exploited those initial challenges to the Syrian regime, seeing them as an opening. They did not do so to help democracy activists but to advance their own, largely shared agendas. They used Sunni jihadist groups like al-Qaeda and ISIS to advance their interests, which depend on the break-up of the Syrian state and its replacement by an anarchy that empowers them while disempowering their enemies in the region.

Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states want Iran and its Shia allies weakened; Turkey wants a freer hand against Kurdish dissident groups in Syria and elsewhere; and Israel wants to foster the forces of sectarianism in the Middle East to undermine pan-Arab nationalism, thereby ensuring its regional hegemony will go unchallenged.

The agents trying to stabilise Syria are the regime itself, Russia, Iran and Hizbollah. Their concern is to use whatever force is necessary to repel the agents of anarchy and restore the regime’s dominance.

Neither side can be characterised as “good”. There are no “white hats” in this gunfight. But there is clearly a side to prefer if the yardstick is minimising not only the current suffering in Syria but also future suffering in the region.

The agents of stability want to rebuild Syria and strengthen it as part of a wider Shia bloc. In practice, their policy would achieve – even if it does not directly aim for – a regional balance of forces, similar to the stand-off between the US and Russia in the Cold War. It is not ideal, but it is far preferable to the alternative policy pursued by the agents of anarchy. They want key states in the Middle East to implode, as has already happened in Iraq and Libya and has been partially achieved in Syria.

We know the consequences of this policy: massive sectarian bloodspilling, huge internal population displacement and the creation of waves of refugees who head towards the relative stability of Europe, the seizure and dispersal of military arsenals that spur yet more fighting, and the inspiration of more militant and reactionary ideologies like that of ISIS.

If Syria falls, it will not become Switzerland. And if it falls, it will not be the end of the “war on terror”. Next, these agents of anarchy will move on to Lebanon and Iran, spreading yet more death and destruction.