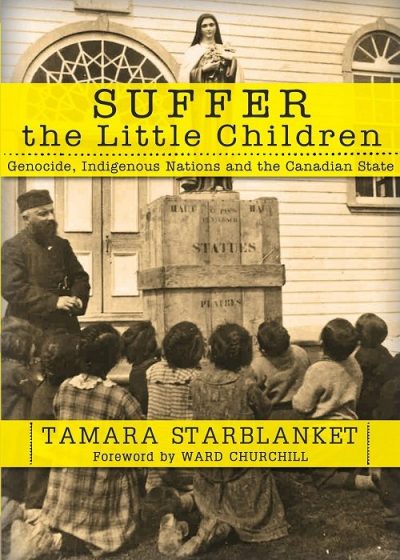

Suffer the Little Children: Genocide, Indigenous Nations and the Canadian State

Review of Tamara Starblanket’s Book

Tamara Starblanket’s book, Suffer the Little Children: Genocide, Indigenous Nations and the Canadian State (with a foreword by Ward Churchill and an afterword by Sharon H. Venne), does what she declares it to do in the first chapter:

“… to serve as a battering ram in which to hammer through the wall of denial.”

She accomplishes her purpose and more in this compelling and well-researched book, which is even more necessary to read in light of the recently released Federal Government Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Women and Girls, and the racism evident in commentaries in the mass media about it. The latter is exemplified by Hymie Rubenstein’s article in the National Post on June 7 that opened using the phrase “first Settlers” with reference to the Indigenous nations, and used the phrase “post-Colombian explorers” to describe the European invaders who destroyed the Indigenous cultures of the Americas. Rubenstein then proceeded to mock the claims that the murders were part of the genocide conducted against Indigenous peoples in Canada.

The book is an effective analysis of the legal structures the Canadian state set up to accomplish its objective: the complete absorption of Indigenous peoples into the dominant European culture, to solve the “Indian problem,” as one Canadian, Duncan Scott, the official in charge of the Department of Indian Affairs, described it:

“By eliminating them as a people, as a culture, to make them disappear.”

We see similar efforts in all of the colonial states. We see it now with President Trump’s new plan to solve the Palestinian problem, to disappear them as a people and culture by having them made citizens of other countries. Palestinians would just cease to exist as Palestinians. This is what the Canadian state has tried to do since its foundation with respect to the Indigenous peoples.

Starblanket begins with a preliminary discussion of the use of language to mask and justify the policies carried out to achieve the colonial objective, a subject more fully developed in later chapters. Then with the First Chapter, titled Naming the Crime, she presents the history of the drafting of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide of 1948, and the concept of genocide that was first used by Raphael Lemkin.

She makes the irrefutable argument that deliberate destruction of a people’s culture is a form of genocide, as Lemkin intended. She exposes how the Canadian state, from the outset, opposed the inclusion of cultural genocide into the definition of genocide and its inclusion in the Genocide Convention, opposition that reflected and still reflects Canada’s actual internal policy of conducting a cultural genocide against the original peoples of what is now Canada.

The sophistry of the Canadian representatives exposed in the debates on the Convention in the General Assembly compares to that of the Nazis who tried to justify their racial extermination policies. Canada constantly opposed the inclusion of cultural genocide, even while claiming that it was opposed to such policies. To add to the insult, the Canadian delegates stated such an issue could only refer to the issue of the rights of the French and English in Canada. Indigenous peoples were deliberately omitted from mention. They took the American government position that only the physical extermination of a people could be considered genocide while Lemkin made it clear that the essence of genocide was both the cultural and physical elimination of a people and that a people could be erased by the suppression of their culture just as much as by physical extermination.

However, in line with their support of liberation and anti-colonial movements around the world, the socialist nations strived to have cultural genocide retained in the Convention. The USSR and other socialist nations held to their position that cultural genocide is a central tenet of the crime. The Yugoslav representative in the General Assembly debates stated cultural genocide was necessary since colonial nations were engaging in such practices the world over. He further complained that the draft did not mention the crimes of Nazism and fascism, which gave the impression that these racist ideologies were excluded from direct condemnation in order to permit their rehabilitation at a future date, a prescient statement since we now witness the rise of political parties across Europe and in North America with racist platforms. He stated that genocide had been, “arbitrarily dissociated from fascist and Nazi ideologies of which, nevertheless, it was the direct result,” and that “in order to suppress genocide, its real causes must be destroyed, namely doctrines of racial and national superiority.”

The Soviets in trying to amend the Convention stated, through their delegate, and in opposition to Canada’s view that oppression of a culture should be a matter for human rights conventions, not the Genocide Convention, stated,

“It was not sufficient for the declaration of human rights, (which deal with individual rights,) to deal with the cultural protection of groups. Such protection should be ensured by the convention on genocide,”

and that,

“… To say that the crime of genocide had no connection with racial theories (e.g. fascist and Nazi theories) amounted in fact to a re-instatement of such theories.”

And,

“the crime of genocide formed an integral part of the plan for world domination of the supporters of racial ideologies.”

The author then guides us into the focus of her book, the forced transfer of children as a method of cultural domination and rightly compares the Canadian policy in that regard to that of the Nazis in their occupied territories in eastern Europe, both of which used propagandistic language to justify the policy.

The balance of the chapter includes an examination of the legal requirements of action and intent required to support a charge of genocide and relates those elements to the forced transfer of children to residential schools. These residential schools were in place in order to subject them to physical and psychological techniques designed to break their will, strip them of their identity and transform them into a broken people with broken spirits, reducing them to half-beings.

The second chapter, titled The Horror, is exactly that. It sets out the facts regarding the Canadian government’s policies aimed at systematically and forcibly removing children from their homes to be placed in confinement in institutions where their sense of themselves as members of a people and having a culture were squeezed out of them through indoctrination, and mental and physical torture. To read the crimes that were committed on a systematic and continuing basis for over a hundred years is indeed a descent into horror. The residential schools staffed by European sadists and racists were nothing less than concentration camps in which indoctrination was constant, along with physical and mental punishments and methods. Children were forcibly removed from their families by government decree. If Elders or leaders objected, their peoples were threatened with starvation.

Upon arrival, the children were given numbers, shorn of their hair, made to wear prison-like uniforms, forbidden to use their real names and forced to use English names instead, forbidden to speak their language, to practice their religion, to see their families, were kept on near starvation rations, punished for any disobedience, and were used as forced labour.

Punishments included beatings, sexual abuse, electric shock, isolation in cupboards, whipping, insults, deprivation of food, more severe forced labour. It makes the mind spin and the stomach churn to learn that what has been going in Canada in the past century and more is similar to what the Nazis did in their concentration camps. The author provides the evidence that in fact, the death rate in the Canadian camps was greater than in Nazi camps like Dachau, and that up to 50% of children died of tuberculosis they acquired at these places.

It is nearly impossible to take in that single fact: a 50% death rate in some institutions. The psychological and cultural damage, is just as great since the children could never adapt to the European culture, were denied their own and so, suffered all of the problems that come with loss of identity, family, and love, replaced with years of fear, and years of loneliness and trauma for those who survived the ordeal.

In the third chapter, Coming to Grips With Canada as a Colonizing State, Starblanket connects this horror to the colonial history of the state that is Canada and the racist ideologies used to justify colonization by the Europeans as they invaded and destroyed existing nations and cultures across Canada. There are references to a number of other works to explain the self-justifications still used today by the colonial nation for its crimes. An example is the “apology” provided by the former Prime Minister of Canada, Stephen Harper, that the government was forced to make under pressure from human rights and Original Peoples to take responsibility for their crimes and take action to compensate the victims. The result was an evasive apology in which the words “neglect” and “abuse” were used instead of “crimes” and a compensation system imposed that paid lip service to the idea while handing out paltry sums with as much resistance as possible. Prime Minister Trudeau used similar terms in his speech to the UN General Assembly.

Starblanket further explains that this system of cultural genocide is perpetuated today as a result of the breakdown of the family system and consequent removal of Indigenous children to state institutions by child welfare agencies and the forced adoption of children to families in Canada and the USA. In this regard, I once represented a man who was forcibly taken from his Cree mother as a boy, shipped off to New York City, given to a white family and was not allowed to return home until he was an adult. It appears he was not the only child to be kidnapped and shipped off—not even to a foster family in Canada but outside of the county—to foreigners as if they were commodities or slaves.

She refers to the unequal application and enforcement of the various treaties established between the British/Canadian governments and the Indigenous nations. It is notorious that all of the treaties have been violated in every region of Canada. One of the most singular facts about the treaties is that the Indigenous nations are not treated as equal nations in the documents; rather the treaties refer to them as wards of the state, as inferiors, as children to be taken care of. None of them were entered into with any proper authority from the peoples concerned or with any other purpose for the Canadian state except to obtain control of the peoples concerned. The Indian Act and the Department of Indian Affairs completed the subjugation and continued the treatment of Indigenous peoples as inferiors, as children in need of care to this day, in line with the superior view of themselves that is inculcated into the European Canadian mind at an early age.

In the following chapter titled Smoke and Mirrors: Canada’s Pretence of Compliance, Starblanket further examines the Canadian factual record in light of the claims of the Canadian state that it had not and does not engage in any deliberate acts of genocide. She once again sets out the evidence from government policies, government statements, and apologies that Canada has committed acts of genocide against indigenous peoples and did so with the intent necessary to result in convictions. She uses findings by the International Court of Justice, and the ad hoc United Nations tribunals for Yugoslavia and Rwanda to support her argument as well as the status of customary international law. She further argues that Canada, by including certain elements of the crime of genocide from the Convention in its domestic Criminal Code, but leaving out the forcible transfer of children, both tried to evade its responsibility for the crimes and provided a loophole for them to continue. This, she rightly argues, is tantamount to trying to derogate from the peremptory norms of international law (jus cogens), one of which is the prohibition against acts of genocide as set out in the Convention, and is a violation of both the Convention and jus cogens.

Though in my view, the judgements of the ad hoc UN tribunals related to Yugoslavia and Rwanda are not legitimate since ad hoc tribunals are not legitimate under the UN Charter, and whose judgements were all politically biased, she was nevertheless right to use them in her analysis since they are generally used and accepted in discussions of these issues. One can conclude that she does not mention the International Criminal Court and the Rome Statute since the genocide clause in the Rome Stature only came into effect in late 2017 and there is no jurisprudence available yet from this tribunal to add to her analysis.

Starblanket completes the book with the last chapter titled The Way Ahead: Self Determination is The Solution, a plea for the Canadian European population to recognise what has been done by them to the Indigenous peoples as a first step forward, because if we do not recognise the crimes, nothing will be done to change the attitudes, actions and policies that led to them. She argues that the Truth and Reconciliation process accomplished nothing since it was designed to mask the true reality of those policies, to protect politicians and officials from criminal responsibility for their actions, and to perpetuate the status quo.

Therefore, the way ahead is for the Peace and Friendship Treaties to be honoured in the sense that they were entered into by the Indigenous peoples, that is, as expressions of friendship and sharing between the Indigenous peoples and the European occupiers. She argues correctly that none of the lands now occupied by the European state created in Canada were surrendered to that state and Indigenous sovereignty over them remains; for too long the Canadian state has acted as overlord. It now has to act as a supplicant, and sit down and renegotiate the relationship between it and the Indigenous nations, to acknowledge that the Indigenous nations are sovereign and need their independence restored. To this end, the Indian Act and its colonial legacy must be abolished and replaced with real self-determination over their lands and peoples.

Starblanket’s book is all the more relevant and necessary to read in light of the recently released Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. In a note to the Report, the committee members state, “This is an important moment in the Truth and Reconciliation journey. …They no longer need to convince others that genocide is a part of Canadian history.”

Not a word about compensation. Not a word about criminal responsibility. Not a word about self-determination. Instead, we have more of the same old platitudes with their “calls for justice” such as an Indigenous Human Rights Ombudsman and related tribunal, when the ineffectiveness of these bodies, when controlled by the state guilty of the crimes, is known, such as a national action plan for employment, housing, health care, the lack of which is due to the actions of the state in deliberately pauperising the peoples concerned; such as abuse education programs when prevention is need. But they do include a call to prohibiting the apprehension of children on the basis of poverty and cultural bias. How this is to be accomplished remains to be seen, but Tamara Starblanket’s book must be read and considered by the Committee, the government, Indigenous peoples and the European population of Canada as part of the way ahead. It should be in every law library, required reading in law schools, and part of every lawyer and citizen’s library. Only then can you understand what Canada is and, with the independent and sovereign Indigenous nations, what it could be.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Christopher Black is an international criminal lawyer based in Toronto. He is known for a number of high-profile war crimes cases and recently published his novel “Beneath the Clouds. He is a frequent contributor to Global Research.