Sudan- Egypt Relations Further Strained over Territorial Dispute. The Hala’ib Triangle

Khartoum takes case before the United Nations amid disagreements over broader regional issues

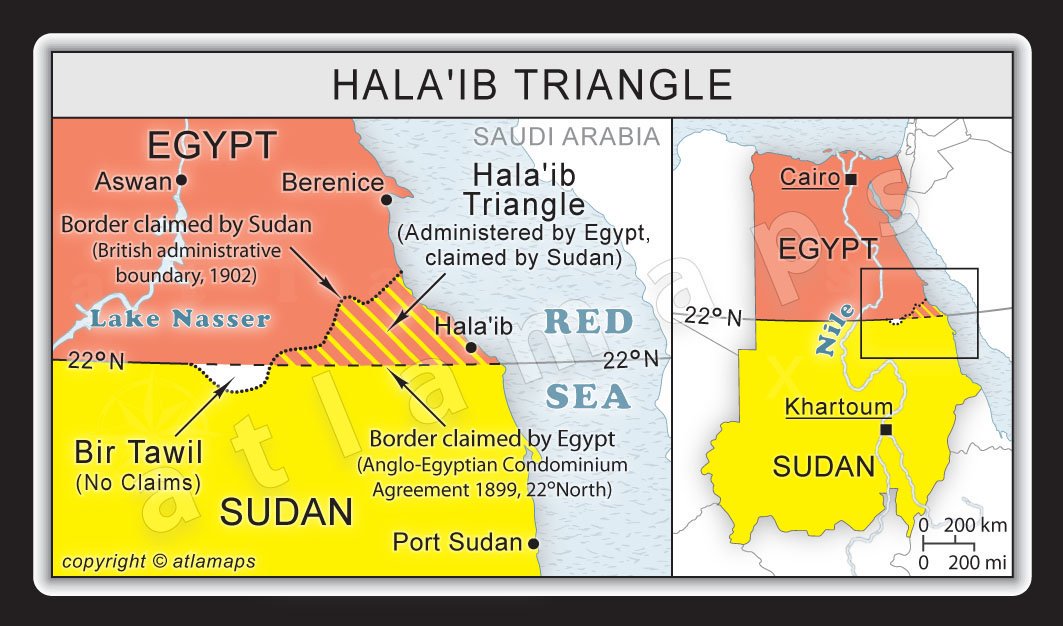

Two leading African states, Egypt and Sudan, are maintaining their historical claims over sovereignty of the Hala’ib Triangle.

Both nations have argued about whether the area belonged to either of them at least since 1958. On January 8, the Sudanese Foreign Ministry took its complaint to the United Nations.

The appeal to the UN followed the withdrawal of the Sudanese Foreign Minister Abdel-Mahmoud Abdel Halim from Cairo for consultations on January 4. Egypt suggested that the recall was a hostile move designed to escalate tensions.

Egyptian Member of Parliament Mona Mounir seems to have expressed the sentiments of the government saying:

“We respect the Sudanese people and their political leadership. However, this escalation (summoning the ambassador) is unjustified.”(Arab News, Jan. 6)

She continued emphasizing that Egypt was willing:

“to discuss and negotiate everything with neighboring Sudan, except what might affect Egypt’s historic share of the (Nile) water and it’s documented and recognized borders.”

Mounir said the recall of Sudanese Ambassador Abdel Halim “will never deter us from protecting every inch of our territory.”

Cairo in 2016 rejected offers of negotiations by Khartoum which was willing to accept international arbitration to determine which state has legal authority to claim Hala’ib Triangle as its national territory. Sudan considers Egypt’s presence in the area as an occupation.

Egypt has rejected the notion that it is occupying Hala’ib and pledged to send a letter as well to the UN in response to the appeal by Khartoum. Egypt says in this letter it will make a case for sovereignty over the area.

During November 2017 Sudanese Foreign Minister Ibrahim Al-Ghandour stressed that Khartoum would never give up Hala’ib. Subsequently the Director of Sudan’s Technical Committee for Border Demarcation (TCBD), Abdullah Al-Sadiq, on January 4 reemphasized that Khartoum would not relinquish its claim to Hala’ib.

Al-Ghandour expressed the desire for a peaceful resolution saying the ongoing “Egyptian infringement” on Sudanese territory could prompt Khartoum to engage in military actions that would be disadvantageous for Cairo. Both Sudan and Egypt have formidable militaries within an Africa context where an outbreak of fighting would have regional and international implications.

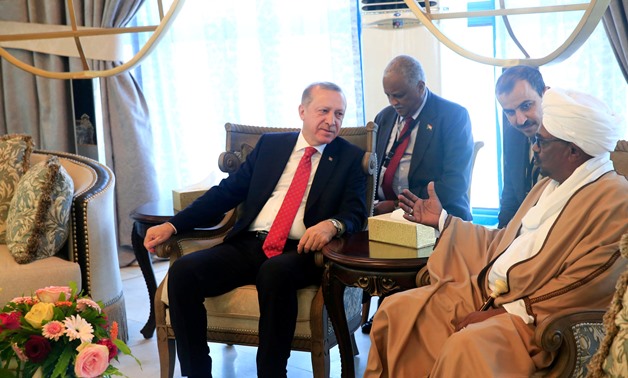

Sudan and Turkey Presidents hold meeting

The disagreements between the two governments is also related to the recent visit by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan where it is reported that an agreement was signed for the construction of a military base on the Red Sea island of Suakin in northeast Sudan. Coinciding with the visit of Erdogan was the presence of Qatari military Chief of Staff Ghanim bin Shaheen al-Ghanim.

Suakin Island was a major port during the Ottoman Empire beginning in the early 16th century when there were intense military conflicts with Portugal over control of the area. Historically it is considered one of the most lucrative territories in the region and the renewed interests by Turkey is perceived as a major impediment by Egypt to its strategic and security interests.

Consequently, Egypt is viewing the presence of these two adversarial leaders as part of a broader plan to fortify Sudanese military positions in opposition to Cairo. Both Turkey and Qatar objected strongly to the military coup against former Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood during July 2013. The putsch was led by the current President Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi.

Morsi remains in prison along with thousands of other members and supporters of the Freedom and Justice Party, the political wing of the Muslim Brotherhood. The organization has been outlawed while the country prepares for another election in March 2018. Al-Sisi is expected to stand for re-election after winning office in 2014 when he took off his military uniform and replaced it with civilian clothing.

The Colonial Legacy of the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium (1899-1956)

This conflict over the Hala’ib Triangle cannot be separated from the intervention of British imperialism in the region during the late 19th century. In an effort to enhance its colonial ambitions London sought to administer both Sudan and Egypt as one entity ostensibly to protect its investments in the Suez Canal after 1873.

Resistance to British conquest in Sudan followed the seizure of key areas in Egypt by the Royal military forces in 1882. Under the guise of restoring order after an anti-Christian rebellion directed against Europeans, the British army bombarded the city of Alexandria.

Hali’ab Triange map

There was considerable opposition in Sudan to the British-dominated Egyptian regime. A Islamic religious movement surfaced under the leadership of Muhammad Ahmed who later proclaimed himself as the Mahdi, an anointed figure destined to spread the religion aimed at overturning both Turkish and western-oriented secular legal systems.

Initial attempts by the British colonialists to subdue the Mahdi Rebellion were met by successful resistance resulting in the expansion of the rule of the Mahdi and his followers. Later the British sent soldiers into Sudan thinking they would quickly subdue the territory.

Nonetheless, according to the blackpast.org website related to these historical developments:

“By 1882 the Mahdist Army had taken complete control over the area surrounding Khartoum. Then, in 1883, a joint British-Egyptian military expedition under the command of British Colonel William Hicks launched a counterattack against the Mahdists. Hicks was soon killed and the British decided to evacuate the Sudan. Fighting continued however and the British-Egyptian forces which defended Khartoum in a long siege were finally overrun on January 28, 1885. Virtually the entire garrison was killed. General Charles Gordon, the commander of the British-Egyptian forces, was beheaded during the attack.”

This same report continues saying that:

“In June 1885, Ahmad, the self-proclaimed Mahdi, died. As a result the Mahdist movement quickly dissolved as infighting broke out among rival claimants to leadership. Hoping to capitalize on internal strife, the British returned to the Sudan in 1896 with Horatio Kitchener as commander of another Anglo-Egyptian army. In the final battle of the war on September 2, 1898 at Karari, 11,000 Mahdists were killed and 16,000 were wounded.”

By 1899 the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium was established by the British which administratively laid down the framework for the ongoing disagreements over boundaries, access to waterways and islands throughout the region extending into the 20th and 21st centuries. After renewed rebellions, general strikes and political agitation from the early 1900s to the mid-1950s, Sudan was declared independent in 1956.

Unfortunately, Sudan and Egypt have not been able to resolve their differences related to this issue on a diplomatic and legal basis. The situation involving Hala’ib is reflective of the heightening tensions over the Blue Nile where the flow of water throughout the entire basin is raising the potential for military conflict between Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia.

The Great Ethiopian Renaissance Dam Project and the Status of Egypt

In addition to the recrudescent conflict surrounding border demarcations between Sudan and Egypt stemming from the historic Ottoman and British domination during the 16th to the early 20th centuries, there is the opposition by Cairo to the construction of the Ethiopian Great Renaissance Dam Project. There appears to be an alliance by Khartoum with the other eight Nile Basin states which are supportive of the building of the dam and the vision that the endeavor will benefit the entire North and East Africa regions.

Through the de facto domination of Britain, France and eventually the United States over the domestic and foreign affairs of Egypt since the late 1800s, the waters of the Nile River have been the channeled for the benefit of Cairo and to a lesser extent Khartoum. Nevertheless, in the recent period the nations of the Nile Basin have sought to exert their voice on the future of these regions of the continent. A Nile Basin Initiative group was formed in 1999 which includes Burundi, DR Congo, Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, The Sudan, Tanzania and Uganda, while Eritrea participates as an observer.

This represent a significant departure from the colonial period when the concerns of countries further south along the Nile took on secondary importance to areas closer to the Mediterranean and the Suez Canal. A Comprehensive Framework Agreement (CFA) was adopted in 1999 calling for a reconfiguration of economic priorities. Sudan and later Egypt have accepted the ideas behind the CFA, although differences remain particularly between Cairo and the other Nile Basin states.

An article published by The National based in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) says that Egypt advanced its own development trajectory through the construction of the Aswan Dam in the south of the country during the 1960s. The damn opened in 1970 having been built through the efforts of the Soviet Union. The-then President Gamal Abdel Nasser had nationalized the Suez Canal in 1956 prompting an unsuccessful invasion by Britain, France and the State of Israel.

The National emphasized that:

“The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, which is still under construction, may not have such dramatic consequences, but it has triggered intense controversy throughout the Nile basin. When completed, it will be the biggest hydroelectric plant in Africa with 6,450 megawatts of generating capacity. Despite a booming economy and a population of 102 million, the second-largest in the continent, Ethiopia has just 4,290MW installed today. Egypt’s slightly smaller population has 38,000MW. Under the 1959 Nile Waters Agreement, Egypt and Sudan agreed [to] their shares of the Nile’s flow at 55.5 billion cubic metres and 18.5bn m3, respectively. This treaty was reached without reference to the other riparian states, a situation resented by Ethiopia, which supplies 80 per cent of the river’s flow.”

These post-colonial difficulties should be resolved within the framework of the Africa Union (AU), other regional organizations or the UN. Within the context of a continuing economic crisis in both Egypt and Sudan, the potential for military conflict is quite real.

Such a decline in diplomatic relations sets the stage for a situation where millions of people in Egypt and Sudan can be grossly impacted in a negative fashion. The level of population dislocation, injuries, deaths, economic collapse, along with the possible interventions of governmental entities based outside of Africa which would stem from a full-blown war between Cairo and Khartoum, warrants that both states enter into some effective methods designed to reach a permanent resolution to the dispute.

*

All images, except the featured, in this article are from the author.