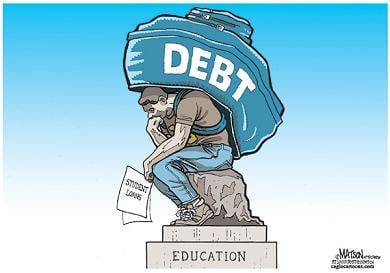

Student Loans: The Government is Now Officially in the Banking Business

“We say in our platform that we believe that the right to coin money and issue money is a function of government. . . . Those who are opposed to this proposition tell us that the issue of paper money is a function of the bank and that the government ought to go out of the banking business. I stand with Jefferson . . . and tell them, as he did, that the issue of money is a function of the government and that the banks should go out of the governing business.” William Jennings Bryan, Democratic Convention, 1896

William Jennings Bryan would have been pleased. The government is now officially in the banking business. On March 30, 2010, President Obama signed the reconciliation “fix” to the health care reform bill passed by Congress last week. Slipped into it was student loan legislation the President calls “one of the most significant investments in higher education since the G.I. Bill.” Under the Student Aid and Fiscal Responsibility Act (SAFRA), the federal government will lend directly to students, ending billions of dollars in wasteful subsidies to firms providing student loans. The bill will save an estimated $68 billion over 11 years.

Money for the program will come from the U.S. Treasury, which will lend it to the Education Department at 2.8% interest. The money will then be lent to students at 6.8% interest. Eliminating the middlemen will allow the Education Department to keep its 4% spread as profit, money that will be used to help impoverished students. If the Education Department were to set up its own bank, on the model of the Green Bank being proposed in the Energy Bill, it could generate even more money for higher education.

A Failed Experiment in Corporate Socialism

The student loan bill may look like a sudden, radical plunge into nationalization, but the government was actually funding over 80 percent of student loans already. Complete government takeover of the program was just the logical and predictable end of a failed 45-year experiment in government subsidies for private banking, involving unnecessary giveaways to Sallie Mae (SLM Corp., the nation’s largest student loan provider), Citibank, and other commercial banks exposed in blatantly exploiting the system.

Under the Federal Family Education Loan Program (FFELP), the U.S. government has been providing subsidies to private companies making student loans ever since 1965. Every independent agency that has calculated the cost of the FFELP, from the Congressional Budget Office to Clinton’s Office of Management and Budget to George W. Bush’s Office of Management and Budget, has found that direct lending could save the government billions of dollars annually. But the mills of Congress grind slowly, and it has taken until now for this reform to work its way through the system.

In the sixties, when competing with the Soviets was considered a matter of national survival, providing the opportunity for higher education was accepted as a necessary public good. But unlike Russia and many other countries, the U.S. was not prepared to provide that education for free. Loans to students were necessary, but students were notoriously bad credit risks. They were too young to have reliable credit histories, and they did not own houses that could be posted as collateral. They had nothing but a very uncertain hope of future gainful employment, and banks were not willing to take them on as credit risks without government guarantees.

The result was the FFELP, which privatized the banks’ profits while socializing losses by imposing them on the taxpayers. The loans continued to be “originated” by the banks, which meant the banks advanced credit created as accounting entries on their books, the way all banks do. Contrary to popular belief, banks do not lend their own money or their depositors’ money. Commercial bank loans are new money, created in the act of lending it. The alleged justification for allowing banks to charge interest although they are not really lending their own money is that the interest is compensation for taking risk. The banks have to balance their books, and if the loans don’t get paid back, the asset side of their balance sheets can shrink, exposing them to bankruptcy. When the risk is underwritten by the taxpayers, however, allowing the banks to keep the interest is simply a giveaway to the banks, an unwarranted form of welfare to a privileged financier class at the expense of struggling students.

Worse, underwriting these private middlemen with government guarantees has allowed them to game the system. Under the FFELP, banks actually profit more when students default than when they pay back their loans. Delinquent loans are turned over to a guaranty agency in charge of keeping students in repayment. Pre-default, guaranty agencies earn just 1 percent of the loan’s outstanding balance. But if the loan defaults and the agency rehabilitates it, the guarantor earns as much as 38.5% of the loan’s balance. Collection efforts are also much more profitable than efforts to avert default, giving guaranty agencies a major incentive to encourage delinquencies. In 2008, 60.5% of federal payments to FFELP came from defaults. An Education Department report issued last year found that only 4.8% of students who borrowed directly from the government had defaulted on their loans in 2007, compared to 7.2 percent for FFELP; and the gap widened when longer periods were taken into account.

In 1993, students and schools were given the option of choosing between FFELP and the Direct Loan program, which allowed the government to offer better terms to students. The Direct Loan program was the clear winner, growing from just 7% of overall loan volume in 1994-1995 to over 80% today.

The demise of the FFELP was hastened in early 2007, when New York Attorney General Andrew Cuomo began exposing the corrupt relations between firms lending to students and the colleges they attended. Lenders that had been buying off college loan officials were forced to refund millions of dollars to borrowers.

Congress responded by cutting the private lenders’ subsidies. But after the 2008 economic crash, the lenders claimed they could no longer afford to lend to low-income (high-risk) borrowers without these subsidies. Congress therefore acquiesced with a May 2008 law requiring the federal government to give banks two-thirds of the funds lent to students. The bill also required the Education and Treasury Departments to buy loans from lenders made between May 2008 and July 2009 for the full value of the loans plus interest. To comply with this bill, the Department of Education projects that it will eventually have to buy $112 billion in FFELP loans.

Despite all this government help, lenders have continued to turn their backs on riskier borrowers, driving students to the government’s direct lending program. With the banks enjoying heavy subsidies while failing in their mission, Obama campaigned in 2008 on a promise of eliminating the middleman lenders; and with the new SAFRA, he appears to have fulfilled that goal.

And thus ends a 45-year experiment in subsidized student lending. In the laboratory of the market, direct lending from the government has proven to be a superior alternative for both taxpayers and borrowers.

The U.S. is not the only country exploring government-sponsored student loan programs. New Zealand now offers 0% interest loans to New Zealand students, with repayment to be made from their income after they graduate. And for the past twenty years, the Australian government has successfully funded students by giving out what are in effect interest-free loans. They are “contingent loans,” which are repaid if and when the borrower’s income reaches a certain level.

Where Will the Money Come From?

The Green Bank Model

Eliminating the middlemen can reduce the costs of federal lending, but there is still the problem of finding the money for the loans. Won’t funding the entire federal student loan business take a serious bite out of the federal budget?

The answer is no – not if the program is set up properly. In fact, it could be a significant source of income for the government.

The SAFRA doesn’t mention setting up a government-owned bank, but the Energy Bill that is now pending before the Senate does. Funding for the energy program is to be through a Green Bank, which can multiply its funds by leveraging its capital base into loans, as all banks are permitted to do. According to an article in American Progress:

“Funding for the Green Bank should be on the order of an initial $10 billion, with additional capital provided of up to $50 billion over five years. This capital could be leveraged at a conservative 10-to-1 ratio to provide loans, guarantees, and credit enhancement to support up to $500 billion in private-sector investment in clean-energy and energy-efficiency projects.”

Banks can create all the credit they can find creditworthy borrowers for, limited only by the capital requirement. But when the loan money leaves the bank as cash or checks, banking rules require the bank’s reserves to be replenished either with deposits coming in or with interbank loans. The proposed Green Bank, however, is apparently not going to be a deposit-taking institution. Presumably, then, it will be relying on interbank loans to provide the reserves to clear its checks.

The federal funds rate – the rate at which banks borrow from each other – has been maintained by the Federal Reserve at between zero and .25% ever since December 2008, when the credit crisis threatened to collapse the economy. A Green Bank qualified to borrow in the interbank market could acquire funds at that very low rate as well, and so could a Student Bank. The spread could give the Education Department more than 6.5% gross profit annually on student loans.

The Treasury, by contrast, paid an average interest rate for marketable securities in February 2010 of 2.55%, which explains the 2.8% interest at which the Education Department must now borrow from the Treasury. The interbank rate is obviously a better deal, but it could go up. The cheapest and most reliable alternative would be for the Treasury itself to become the “lender of last resort,” as William Jennings Bryan urged in 1896.

The Treasury Department and the Education Department are arms of the same federal government. If the government were to set up a government-owned bank that simply lent “national credit” directly, without borrowing the money first, it could afford to lend to students at much lower rates than 6.8%. In fact, it could afford free higher education for all. Such a program could actually pay for itself, as was demonstrated by the G.I. Bill, considered one of the government’s most successful programs. Under the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, the government sent seven million Americans to school for free after World War II. A 1988 Congressional committee found that for every dollar invested in the program, $6.90 came back to the U.S. economy. Better-educated young people got better-paying jobs, resulting in substantially higher tax revenues year after year for the next forty-plus years.

Taking Back the Credit Power

Winston Churchill once wryly remarked, “America will always do the right thing, but only after exhausting all other options.” More than a century has passed since William Jennings Bryan insisted that issuing and lending the credit of the nation should be the business of the government rather than of private bankers, but it has taken that long to exhaust all the other options. With student loans, at least, government officials have finally come around to agreeing that underwriting private lenders with public funds doesn’t work.

We are increasingly seeing that underwriting banks considered “too big to fail” doesn’t work either. Banks are borrowing at near-zero interest rates and speculating with the money, knowing they can’t lose because the government will pick up the losses on any bad bets. This is called “moral hazard,” and it is destroying the economy.

Issuing the national credit directly, through a federally-owned central bank, may be the only real solution to this dilemma. Today the government borrows the national currency from the privately-owned Federal Reserve, which issues Federal Reserve Notes and lends them to the government and to other banks. These notes, however, are backed by nothing but “the full faith and credit of the United States.” Lending the credit of the United States should be the business of the United States, as William Jennings Bryan maintained. The dollar is credit (or debt), just as a bond is. Both a dollar bond and a dollar bill represent a claim on a dollar’s worth of goods and services. As Thomas Edison said in the 1920s:

“If the Nation can issue a dollar bond it can issue a dollar bill. The element that makes the bond good makes the bill good also. The difference between the bond and the bill is that the bond lets the money broker collect twice the amount of the bond and an additional 20%. Whereas the currency, the honest sort provided by the Constitution pays nobody but those who contribute in some useful way. It is absurd to say our Country can issue bonds and cannot issue currency. Both are promises to pay, but one fattens the usurer and the other helps the People.”

Ellen Brown developed her research skills as an attorney practicing civil litigation in Los Angeles. In Web of Debt, her latest of eleven books, she turns those skills to an analysis of the Federal Reserve and “the money trust.” She shows how this private cartel has usurped the power to create money from the people themselves, and how we the people can get it back. Her websites are www.webofdebt.com, www.ellenbrown.com, and www.public-banking.com.

Niko Kyriakou contributed to this article.