Strategies Born In The Mind. What are Russia’s “Intentions”

In May 2019, a curious document was made publicly available under the aegis of the US Defense Department and the US Joint Chiefs of Staff. It is entitled “Russian Strategic Intentions” and was prepared as part of the Strategic Multilayer Assessment programme.

The report is the joint effort of more than 30 authors, including John Arquilla, one of the founders of the Netwar concept; Marlene Laruelle, who has specialised in the ideology of Eurasianism for many years; Daniel Flynn from the US Office of the Director of National Intelligence; and a number of other academics and military officials from relevant organisations, such as the US Military Academy at West Point; the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism; the US Air Force; the Center for Political–Military Analysis at the Hudson Institute; the US Army War College Strategic Studies Institute; the US Central Command; the Naval Postgraduate School; and the USEUCOM Strategy Division & Russia Strategic Initiative.

The list of names also includes several specialists on Russia, such as Anna Borshchevskaya from the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, who has spent years dishing out Russophobic propaganda to US think tanks; and Pavel Devyatkin from The Arctic Institute, who also works with the US Peace Corps, a long-standing NGO that peddles US propaganda and conducts intelligence activities in other countries.

As early as the preface, written by Lieutenant General Theodore Martin from the US Army Training and Doctrine Command, it states that

“Russian actions occurring within the Competitive Zone, or ‘Gray Zone,’ profoundly impact and continue to threaten vital aspects of US national interest and security. Finding a way to understand the overarching campaign plan behind Russian actions will enable the United States to more effectively counter Moscow.”

So, the idea is clear. It is an attempt to think like the Russian government does in order to know for certain which actions the Kremlin will take in the future. Given that the report is broken down into regions – Europe, Central Asia, the Middle East, Africa, Latin America, and the Arctic – it appears that US military and political leaders believe Russia is a threat to the US in all these areas.

Where the recent study by the RAND Corporation openly talks about the various scenarios to be implemented in order to directly or indirectly weaken Russia and hurt its interests in the post-Soviet space and critical areas like Syria, here we see the results of some kind of brainstorming session that was organised to “provide government stakeholders—intelligence, law enforcement, military, and policy agencies—with valuable insights and analytic frameworks to assist the US, its allies, and partners in developing a comprehensive strategy to compete and defeat this Russian challenge.” It sounds almost identical to the Cold War era.

It is telling that, on 8 May, the Strategic Multilayer Assessment, together with the US National Defence University and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, held a panel discussion on the future of global competition and conflict with Russia. The list of speakers (with just as venerable experts and experienced politicians, such as retired Brigadier General Peter Zwack, former US Defense Attaché to Russia, and Angela Stent, director of Georgetown University’s Eurasian, Russian, and East European Studies, who also once served as National Intelligence Officer for Russia and Eurasia) differed from the authors of the report mentioned earlier, which means that these two initiatives are just the tip of an iceberg that is only visible thanks to the publicity of the events.

As well as using current favourite terms like “Grey Zone” and “hybrid warfare”, US experts note in the Executive Summary that,

“[t]he military exercises which Russia conducts regularly require a total mobilization of society”, “Russia increasingly is operating more to save face” (e.g. Venezuela), Russia is seeking to destroy “institutions in Europe”, and even that Russia established the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) “to extend the rules of the Russian economy, and allow Russia access to the policies of privileged sphere nations and further prevent Western encroachment and influence”.

It is interesting that Kazakhstan, for example, in no way reduced its economic relations with the EU after the establishment of the EAEU, but actually increased them. It also makes no mention of the fact that all decisions within the EAEU are reached by consensus. So, when such US academics try to pass off wishful thinking as reality and rationalise certain concepts (such as “Putinism”, “imperial DNA”, and a “new Brezhnev doctrine”), it only serves to show their bias and incompetence. Incidentally, a mysterious flurry of activity around US Army recruiting stations was listed among Russia’s hostile actions. Mysterious because it is only mentioned in the context of “Russia’s influence activities” in the 2016 US presidential election. It goes without saying that no facts or evidence are provided.

As for the report on Russia’s “strategic intentions”, there are no noticeable attempts to penetrate the Kremlin’s thinking, while much is said of the need to reduce Europe’s dependence on Russian gas, of Russia’s near abroad (especially Georgia, Moldova and Donbass), of the activities of the GRU and FSB, of the strategy of “maskirovka” (or military deception), and of Moscow’s machinations.

There is even a fantastic story about Russia exploiting insurgents from the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). (Mention is also made of the Spanish-language television channel Russia Today en Español as an agent of disinformation.)

The view is even expressed that Russia has an “assertive grand strategy”. Allegedly behind this strategy are: the desire of the Russian elite for Russia to be recognised as a great power; the desire to protect Russian identity and a broader Slavic identity; and the desire to see the US global power limited. But desires are not the same as institutionalised practice, which requires resources and certain mechanisms for a plan to be implemented. It is interesting to watch US academics discussing links between the thousand-year history of Rus’, Christianity, the Yalta conference and present-day Russia, of course, but it crosses the line when these digressions get mixed up with the expansion of NATO, the role of the Collective Security Treaty Organisation and the EAEU (Jeremy Lamoreaux), and Russia being credited with the “most aggressive methods […] to achieve its grand strategic vision of a multipolar world defined by exclusive spheres of influence” (Robert Person).

The observation that Russia and America’s strategies on Europe are different, and that what Washington wants, Moscow doesn’t want and vice versa, is true, but it is a long-known truth and does not need further comment.

And listing the various outcomes of Russia’s foreign policy activities is like a digest of Russia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, except with a negative interpretation.

On the whole, there is a noticeable number of clichés and exaggerated metaphors.

Proposals for combating Russian influence include the spread of liberalism; strengthening NATO; recruiting a large number of experienced diplomats; promoting American culture, language, and values; using the private sector as proxy actors in countries neighbouring Russia; squeezing out Russian weapons exports using security cooperation programmes; providing incentives to countries carrying out pro-Western reforms (such as Uzbekistan); and targeted programmes in a number of countries where they can be implemented.

The most rational opinion was probably given by John Arquilla, who noted: “We should think about potential ‘shocks,’ the most troubling of which would be if Putin performed a ‘reverse Nixon’ and played his own version of the ‘China card.’ The world system, and American influence in it, would be completely upended if Moscow and Beijing aligned more closely. Perhaps a good American strategy would be to play a ‘Russia card’ first.”

This is one of those times when the Russian government should do just that, and as soon as possible. Where the minds of US experts have given rise to chimeras that will become the rationale for their next strategy, Russia’s real grand strategy will be based on logical conclusions, sustainable mechanisms, and decisions acceptable to everyone involved.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Leonid Savin is a geopolitical analyst, Chief editor of Geopolitica.ru, founder and chief editor of Journal of Eurasian Affairs; head of the administration of the International Eurasian Movement.

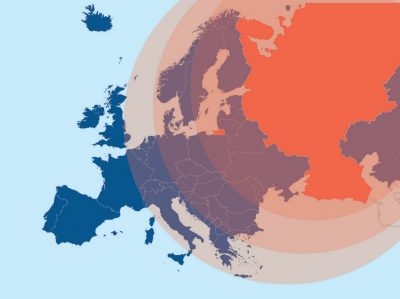

Featured image: Russia’s Hostile Measures in Europe, according to RAND Corporation (Source: OR)