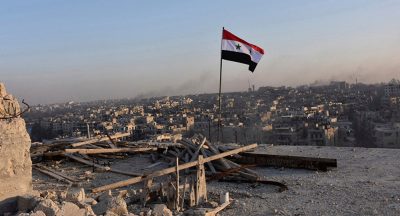

Strategic Assessment of the War on Syria in Fall 2018: Idlib & the Northeast

The onset of three major developments next month will change the entire dynamic of the War on Syria, meaning that the country’s decision makers must urgently assess the true state of strategic affairs as they presently stand, forecast the most probable scenarios that will unfold across the coming months, and seriously consider which policies could help them make the best out of an increasingly difficult situation.

The War on Syria has already lasted almost eight years but is finally approaching its conclusion as the kinetic phase of military conflict gradually makes way for the non-kinetic one of political negotiations and “compromises”. For patriotic reasons, the democratically elected and legitimate government of Syria wants to restore Damascus’ sovereignty over “every inch” of Syria, but this is becoming ever more challenging in light of the present state of strategic affairs and the dramatic changes that are slated to take place next month. It’s imperative that decision makers properly understand the complex international situation that’s thus far impeded their liberation of Idlib and the Northeast, as well as how three forthcoming major developments are poised to fundamentally alter the entire dynamic of the War on Syria, in order to forecast the most probable scenarios across the coming months and deeply reflect on which policy proposals are best suited for advancing the country’s interests under these pressing circumstances.

The Three Game-Changers

Before reviewing the state of play in and around Syria today, it’s necessary to point out the three events that are expected to alter the course of the entire War on Syria, both in its military and political manifestations.

- The US-Imposed October Deadline For Assembling The Constitutional Commission

The US subjectively imposed a deadline of the end of October for the assembling of the UN-supervised Constitutional Committee that was previously agreed upon by all internationally recognized parties of the conflict. In and of itself it wouldn’t matter whether this deadline comes and goes, but the problem is that the US is threatening to tighten its sanctions regime against the country if it doesn’t comply. Not only that, but America also recently announced that it might sanction all foreign companies that participate in Syria’s reconstruction, meaning that Russian companies will certainly fall under this purview and all of their partners could be subjected to so-called “secondary sanctions” because of it.

In other words, a Russian company will have to potentially risk losing all of its Western business contracts if it decides to participate in the Syrian reconstruction process. The workaround is for completely new companies to be created specifically for this purpose (such as “shell companies”), but it can’t be discounted that the US will discover their true connections to the original entity and capture them and their partners in its weaponized sanctions net. This is relevant for Syria because it could lead to Moscow more “actively encouraging” it to accelerate the political process in spite of its official public comments to the contrary in order to avoid these threatened economic complications for its companies.

- The Reimposition Of The US’ Energy-Related Sanctions Against Iran

The US will reimpose its unilateral sanctions against Iran and its energy industry early next month, which crucially includes so-called “secondary sanctions” against all violators. While Iran has survived much worse in the past and has plenty of experience managing what it refers to as its “Resistance Economy”, one shouldn’t underestimate the US’ resolve to bring the Islamic Republic to its knees by making this forthcoming round of economic punishment against it much more severe than everything that came beforehand. This partly has to do with the Trump Administration’s obsession in carrying out regime change against the country, but also with its intentions to increase the political and economic cost of Iran’s military assistance to Syria, which the US considers partly responsible for thwarting its plans in the country.

One of the US’ strategies is to tacitly offer Iran the possibility of sanctions relief if it downscales and ultimately removes its military presence in Syria so that Trump can then trumpet it as one of the greatest-ever successes of his administration even if this “phased withdrawal” is undertaken for reasons that have nothing to openly do with “succumbing to American pressure” like the US might portray it as. Either way, in spite of the ideological alliance that Syria enjoys with Iran, it needs to recognize that Tehran’s military role in the country is becoming one of the most heavily politicized issues in contemporary Mideast geopolitics and that all sides might ultimately have to “compromise” on it in order to keep the situation from uncontrollably escalating to Damascus’ detriment.

- Staffan De Mistura Will Step Down At The End Of November

The UN Envoy to Syria will step down from his post for personal reasons at the end of next month, which regrettably comes at one of the most sensitive political moments for Syria. He’s already said that he would like to assemble the Constitutional Commission before then and is undeniably trying his best to accomplish this task, but his removal from the scene risks undermining the important relationships that he established as the global body’s mediator in this conflict over the past four years of his tenure. This could inadvertently disrupt whatever prospective political gains are made before then, and could even in fact prevent any significant ones from being made in the first place if some of the conflict’s parties deliberately procrastinate on reaching an agreement because of it.

Syria needs to prepare to establish a new working relationship with whomever de Mistura’s successor will be, which might be easier said than done because it’s not yet clear who will replace him. It’s very possible that that individual might be overly biased against Damascus and therefore function as an obstacle to the political process, which could cynically serve to advance the American agenda for Syria by dragging this out way beyond the US’ subjectively imposed deadline and serving as the preplanned pretext for implementing a tougher sanctions regime against the country and its partners. At the same time, however, de Mistura’s resignation could also present an opportunity for all stakeholders to strike a pragmatic deal on the Constitutional Commission before then in order to continue his legacy.

The State Of Affairs

Having described the three impending game-changing developments that will happen next month, it’s now time to evaluate the state of affairs as they presently exist.

Overall:

The kinetic (military) phase of the conflict is gradually giving way to its inevitable non-kinetic (political) one as hostilities abate across the country due to a combination of military gains and “ceasefires”, both of which were achieved through substantial Russian support. The government is still struggling with its desire to liberate “every inch” of Syria, however, because the latest deal in Idlib indefinitely delayed the Syrian Arab Army’s (SAA) offensive on the region, while the so-called “deconfliction line” along the Euphrates River has essentially divided the country into Russian and American “spheres of influence”. About the latter, it should be noted that the US responded with disproportionate and utterly overwhelming military force in February when an attempt was reportedly made by the SAA and its allies to cross the Euphrates, showing that America will not allow any violations of the “gentlemen’s agreement” that it made with Russia in this respect.

For as unfortunate as it is, the reality is that the US has established approximately 20 bases in the agriculturally and energy-rich areas of Northeastern Syria under the control of their Kurdish allies and it’s extremely unlikely that they’ll be removed by force, especially because Russia will not risk an escalation of military hostilities with its rival over this issue. In fact, the Russian position seems to be to “balance” between all parties of the conflict in order to avoid military hostilities that could quickly spiral out of control and derail the political process that it wants to preside over, so Moscow’s military support in liberating the Northeast and Idlib shouldn’t be taken for granted regardless of whatever Syria’s partner says in public or private about this. The simple fact is that the resolution of the Idlib issue will facilitate a political deal in the Northeast and should therefore be prioritized.

Idlib:

Last month’s Russian-Turkish Idlib deal was the culmination of intense diplomacy over the preceding weeks and came to represent the strategic closeness of these Great Powers’ bilateral relations following their 2016 rapprochement. The purpose of the agreement was first and foremost to stop the impending SAA liberation operation in the region that Russia feared could have caused a clash between its Syrian and Turkish partners and therefore led to the rapid unravelling of its delicate “balancing” act between them. It’s irresponsible to speculate about which “side” Russia would support in that scenario, but it shouldn’t be forgotten that Turkey is a comparatively much larger, profitable, and influential partner for Russia than Syria is, so that might reasonably figure into Moscow’s calculations and also explain why it sought to stop the SAA offensive in the first place at the behest of its Turkish partners.

Russia wouldn’t have tried to stop Idlib’s military liberation by the SAA had it not seriously believed that this goal could be “less disruptively” accomplished through its diplomatic contacts with Turkey, which was more than willing to have Moscow implicitly acknowledge its “sphere of influence” in the region by bestowing it with the responsibility to rid the area of terrorists. From Ankara’s perspective, not only did it gain important domestic, regional, and even global prestige through this agreement, but it may have also thought that it could leverage its newfound position of military-political authority here to cement its influence and improve the odds that Idlib could be granted “autonomy” (whether officially or unofficially) throughout the forthcoming course of the political process. Turkey’s end goal in Idlib therefore represents a serious challenge to the restoration of Damascus’ sovereignty in that part of the country.

Northeast:

Like it was earlier explained, the US is strictly enforcing the so-called “deconfliction line” along the Euphrates and doesn’t tolerate any violations of its “gentlemen’s agreement” with Russia. This makes it all but impossible for the SAA to militarily liberate the region, which is why political means will most likely have to be utilized instead. Those will be explained later on in the analysis, but for now it’s important to talk more about the state of affairs in that part of the country today. The US’ 20 or so bases imply that it doesn’t plan to leave the region, probably because it plans to weaponize its agricultural and energy resources by using them to exert influence over the rest of the country. Even in the event that it’s not as successful with this strategic scheme as it would like, then there’s a very high probability that it’ll rely on those resources to reconstruct that relatively less populated and less-destroyed corner of the country.

When coupled with the assistance that the US’ Saudi and other partners will commit to the Kurdish-controlled Northeast, and bearing in mind the weaponized sanctions (both primary and “secondary”) that will be imposed against Damascus’ own reconstruction partners, it’s conceivable that the occupied third of the country will be reconstructed at a faster pace than the rest of it, which will itself be manipulated in future infowar campaigns against Syria to push forward the destabilizing narrative that the “government isn’t capable of rebuilding”. To put it another way, the US is planning to turn the Northeast into an “oasis of prosperity”, or at least superficially so, in order to contrast with the lack of comparative progress elsewhere in Syria. In reality, however, US control over the region is tenuous and upheld by the YPG’s brutal military dictatorship over the majority-non-Kurdish inhabitants, which has also drawn Turkey’s ire and interestingly aligned it with Damascus’ broader interests in the region to a certain degree.

Scenarios

The situation in Syria and each of its two presently occupied regions could unfold in a variety of ways, but there are several that are more likely than others.

Overall:

The trend towards non-kinetic (political) conflict will continue though it should be expected that occasional flashpoints might erupt along the Idlib “de-escalation zone” zone and the Euphrates “deconfliction line”, but it’s extremely improbable that Russia will risk its strategic partnership with Turkey to turn against Ankara to Damascus’ benefit in the first-mentioned region while there’s close to no chance whatsoever that it’ll do the same vis-à-vis the US and possibly even risk a global standoff. This sobering assessment suggests that Syria needs to urgently consider the diplomatic means at its disposal for getting the best possible deal out of each of these two regions in order to bring about a sustainable political solution to the conflict in general. It should be stressed, however, that any prospective deal shouldn’t be against the nation’s interests but instead pragmatically leverage the existing state of affairs to the nation’s best possible benefit given the trying circumstances.

Amidst the diplomatic tango that will inevitably take place between Damascus and the self-proclaimed “authorities” in idlib and the Northeast, as well as between their Great Power backers of Turkey and the US respectively, and interspersed with occasional flare-ups of violence alone the de-facto “lines of control” (predictably smoothed over through Russia’s ”balancing” mediation), one shouldn’t forget about Iran’s comparatively “quieter” but nonetheless increasingly focused-upon position in the country. The onset of US sanctions early next month and the Trump Administration’s obsession with “rolling back Iranian influence” in the Mideast will impose new costs on Tehran’s military assistance to Syria, as well as incentivize Russia to “gently” curtail its partner’s influence out of its own self-interested reasons that it believes to be to the benefit of the region as a whole. This will be returned to once again later in the analysis, though it’s important to keep in mind at this time.

Idlib:

The immediate fate of Idlb hinges on Turkey’s adherence to its joint agreement with Russia to progressively expel terrorist groups from the region. Thus far, it hasn’t been implemented at its expected pace, which has caused some observers to question Ankara’s sincerity. Still, the task at hand is nevertheless enormous and it’s unrealistic to have thought that everything would be handled perfectly and on time, as nothing in this conflict has thus far met any prior deadlines. Taking stock of the situation, one of two probable scenarios will inevitably transpire; either Turkey succeeds in removing terrorists from Idlib or it doesn’t. The first-mentioned will lead to the “de-escalation zone” being frozen in place pending the outcome of the ongoing constitutional reform process which Turkey hopes to influence to its favor by trying to facilitate the bestowment of formal or informal “autonomy” to this region so that it can control it as a proxy state.

As for the second-mentioned possibility, the outbreak of hostilities between the SAA and the Turkish Armed Forces or their “rebel” allies along the Idlib “de-escalation zone” would cause Russia to immediately intervene as a diplomatic mediator between both sides, but it will not “choose” Syria over Turkey under any realistic scenario because there’s simply too much at stake for Moscow to lose if it does. That, however, doesn’t meant that it will behave in an “anti-Syrian” fashion, as it might even carry out a few highly publicized “surgical strikes” against terrorist groups in the region in order to prove that it hasn’t lost its will to fight against these organizations in spite of any potential Turkish failure to completely eradicate them. That said, it should be understood that Russia doesn’t see any direct threat to its own interests from these terrorists because it regards them as “safely contained”, which is another reason why it won’t take Syria’s “side” over Turkey’s.

Northeast:

Source: South Front

The Kurds will continue to expand their administrative control over the region and advance their incipient “state-forming” processes, though they’re cleverly in the middle of “rebranding” their efforts by removing ethnic chauvinist language and symbols in order to give of the misleading impression that they are “inclusive” of the majority-non-Kurdish Arab, Assyrian, and Turkoman inhabitants of the region. This will still probably not prevent occasional revolts from popping up, but they’ll be brutally put down any time that they happen and won’t be reported on by the Mainstream Media. All of this will occur concurrently with their American, European, and Gulf patrons increasing their political, economic, military, and media support to this new sub-state political entity, which will allow it to gain more international “recognition” as a “legitimate” entity that “deserves” to be included in the eventual political solution to the conflict.

For as much as Turkey is opposed to this and has threatened to invade the region if the PYD-YPG Kurds are given a seat at the negotiating table and/or continue to move towards de-facto “autonomy”, Ankara’s ambitions are in the process of being curtailed by the US. The Kurds’ “rebranding” effort is part of the measures designed to calm the Turks down, because for as fearful as they are of this part of Syria being used to support terrorist activity within their own borders, they’re not yet willing to pay the financial, military, and political costs of what could turn into a quagmire through “mission creep”. Furthermore, the presence of so many US bases and servicemen serves as a strong deterrent to any impulsive Turkish military action, and Washington can always exploit the Kurdish threat against Ankara to reach a deal with it concerning Turkey’s assistance to Iran after the forthcoming sanctions.

Recommendations

In light of everything that’s been discussed in this analysis thus far, the following are three general recommendations that are designed to help Syria most effectively deal with the three game-changing developments described earlier in the work and adapt to the most likely scenarios that are forecasted to unfold in the coming future:

- Prepare For The “Phased Withdrawal” Of Iranian Forces From Syria

There should be no doubt in anyone’s mind about Russia’s intentions to “balance” between the West (which includes “Israel”) and Iran in Syria, which it endeavors to do in order to improve its regional diplomatic appeal as the Mideast’s preeminent Great Power and potentially advance a so-called “New Détente” that could ultimately lead to the removal of sanctions. This could prospectively see Russia “encouraging” the “phased withdrawal” of Iranian forces from all of Syria just like it succeeded in doing from around the “Israeli”-occupied Golan Heights in the southwestern part of the country earlier this summer, something that Tehran might actually take Moscow up on if the US’ forthcoming sanctions regime imposes unacceptable costs to the continuance of its military mission in the Arab Republic. In addition, the SAA’s recent anti-terrorist gains all across the liberated portions of the country might no longer require Iran’s support to sustain either.

In the very probable event that American pressure, Russian “balancing”, and the SAA’s anti-terrorist successes combine to create the conditions for Iran to undertake a “phased withdrawal” from the country under dignified conditions and leave the battlefield as heroes, then Damascus must understand exactly what this would entail. Unlike before when Iranian military support pivotally aided the SAA’s liberation of the Damascus suburbs and the southwest of the country, it’s no longer as relevant as it once was in this respect because of the impossibility of repeating these successes in Idlib and the Northeast where the strategic situation is completely different due to the direct military involvement of Turkey and the US. Thus, Iranian forces no longer have any offensive military appeal and only function as unofficial “peacekeepers”, which might not be needed much anymore. Their removal therefore won’t have any negative effects and could jumpstart the political process.

- Take Advantage Of The Last Month Of De Mistura’s Tenure

De Mistura was far from perfect in his position as the UN’s envoy on Syria but he can still be regarded as better than his predecessors. Damascus must therefore take advantage of his last month in that role to assemble the Constitutional Commission or at least make verifiable progress on that goal in order to avoid the ever-intensifying sanctions regime that the US threatened to impose upon it if that doesn’t happen. This isn’t to say that Syria is “submitting” to the US by prioritizing this process, but just that it convincingly appears to be the most pragmatic course of action under the present circumstances of Iran’s possible “phased withdrawal” from the country and Russia’s predicted “encouragement” of Damascus to more seriously participate in this framework afterwards. It’s therefore best for Syria to use de Mistura’s mediating services and solid relationship with the “rebels” to make progress on this issue.

Included in this admittedly controversial recommendation is the possibility for Syria to “play politics” within the group and slow down the pace at which the negotiations unfold after “complicating” them on whatever pretexts can be plausibly utilized once the Constitutional Commission has been assembled. Forming the group itself is designed to buy Syria and its Russian partner time to avoid the promised imposition of tougher sanctions against both of them if it doesn’t adhere to the US’ subjective deadline, which could reasonably be extended to the end of November before de Mistura’s resignation if all sides are sincere in reaching a deal. Just like Syria has done with Astana whenever it was confronted with a proposal that it didn’t approve of like the Russian-written “draft constitution”, so too can it delay proceedings with the Constitutional Commission while giving off the impression that some degree of “progress” has still been achieved.

- Seriously Contemplate The Pragmatic Merits Of Decentralization

There is no way that the SAA will forcibly remove the Turkish military from Idlib and the American one from the Northeast so Damascus needs to be realistic and realize that liberating “every inch” of Syria will have to be accomplished through non-kinetic means within the ambit of the political process. The ideal solution is to restore the central government’s sovereignty over every corner of the country like it was before the war began, but the conflict fundamentally changed Syria and that “maximalist” solution – no matter how ethically, morally, and legally legitimate it is – is no longer feasible so Damascus must play with the cards that it’s dealt at this final stage of the war. Accordingly, asymmetric decentralization modeled off of Russia’s “suggestions” from January 2017 is the most pragmatic way to get all parties to engage in mutually acceptable “compromises” for ending the conflict.

Some constructive proposals include the granting of regional decentralization (“autonomy”) to the Northeast, “judicial autonomy” to Idlib (which would enable it to continue implementing Sharia), and “municipal autonomy” to the major cities so that they have greater rights to independently make legislative and financial decisions. In exchange, the SAA could be deployed along Idlib and the Northeast’s international borders (the latter of which might lessen Turkey’s concerns about Kurdish terrorism there) while the interior of each region might continue to be “policed” by what could be constitutionally legitimized as “regional militias”, understanding that the SAA has no power to disarm and demobilize them given Turkey and the US’ respective presences there. About those, Turkey might be convinced by Russia to withdraw its forces while the Northeast’s “autonomy” might bestow it with the “right” to continue hosting American bases despite Damascus’ principled opposition to this.

Concluding Thoughts

Next month is going to be one of the most important that Syria has experienced since the beginning of the war because of the possible imposition of a more intensified sanctions regime against it and its international reconstruction partners, the geopolitical consequences of the US’ reimposition of energy-related sanctions against Iran, and de Mistura’s departure from his role at the end of November, so it’s incumbent on Damascus to responsibly assess the most likely ramifications of these influential changes and prepare corresponding policies for making the best of these destabilizing developments. Acknowledging the impossibility that the SAA and its Iranian allies can forcibly dislodge the Turkish and American militaries from the country, and accepting that Russia doesn’t regard itself as having any responsibility to help Syria with either of these two tasks (as it believes that its “balancing” role ensures regional peace), then the unavoidable conclusion is that across-the-board political “compromises” must be made by all warring parties.

Damascus cannot restore the centralized state that existed prior to the war, just like the “rebels” can’t overthrow the Syrian government and the Kurds can’t obtain independence. The common denominator of “compromise” between them is therefore the proposed system of asymmetric decentralization that could provide the latter two with differing degrees of “autonomy” that “legitimizes” their unique circumstances at this final stage of the conflict where the battlefront is more or less frozen due to the “gentlemen’s agreements” that Russia reached with their Turkish and American Great Power patrons respectively. It’s inevitable that decentralization in some shape or form will be implemented in Syria as part of the ongoing constitutional reform process, but its specific details – and especially those regarding control of each region’s international borders, the future of their “militias”, and their hosting of foreign military bases – must be discussed further in the context of the Constitutional Commission.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

This article was originally published on Eurasia Future.

Andrew Korybko is an American Moscow-based political analyst specializing in the relationship between the US strategy in Afro-Eurasia, China’s One Belt One Road global vision of New Silk Road connectivity, and Hybrid Warfare. He is a frequent contributor to Global Research.