The Story of Arab-Jews Instills Hope

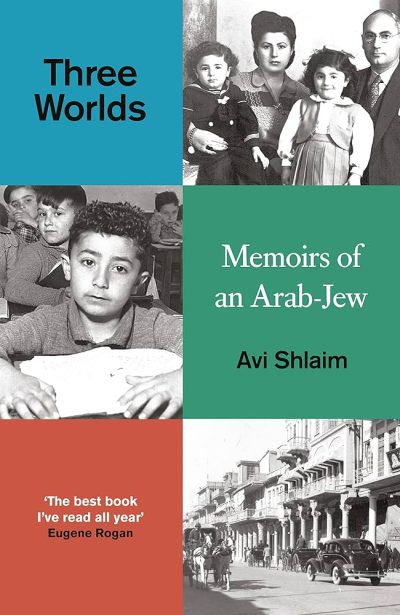

Reflections on Avi Shlaim, Three Worlds: Memoirs of an Arab-Jew, London: Oneworld, 2023, 324 pp.

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name (only available in desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Click the share button above to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Global Research Referral Drive: Our Readers Are Our Lifeline

***

During my stay in Iran in 2016, I heard from several Muslims that Jews are good businessmen because they are trustworthy, and their word weighs more than a notarized contract. I recalled these comments when I read about Yusef, one of the protagonists of this book and the author’s father. A self-made man and a wealthy supplier of building materials, he earned a sterling reputation not only among his customers, but also among his employees, whose welfare, not only their productivity, he constantly cared about.

Yusef also embodies the concept of the Arab-Jew. Active in the Jewish community, sponsor of synagogues and various charities, he was respected and exercised influence. Unlike his wife, a British citizen, he spoke only Arabic and lived in the culture of his country, of which he was an indelible part. His Jewish affiliation was more cultural than religious. Yusef also embodies the gentle and harmonious modernization that is quite different from the often defiant and conflict-ridden modernization of European Jewry.

As usual, at the age of 13, his son Avi is “bar-mitzva ’ed” but there is apparently more emphasis on bar than on mitzva (Torah commandment) during this ceremony. When four years later, Avi arrives in the hostel of a Jewish school in London he is totally unaware that it is Yom Kippur, and surreptitiously eats the ham sandwich brought from the trip across the Channel. Any eating, let alone ham, is, of course, prohibited on Yom Kippur. Compare it with Isaac Deutscher, another Jewish intellectual immigrant to Britain, but this one from Austrian Galicia. Brought up in a deeply religious Hassidic home and considered a Talmud prodigy, he lost his faith and decided to “test God” on Yom Kippur. He went to the tomb of a prominent Hassidic rabbi and ate a ham sandwich. In this act of defiance, the young Deutscher cast away “the yoke of Heaven”. Foodwise, there was no difference, but the different significance of this act points at very dissimilar paths secularization took among Jews in Europe and in the world of Islam.

Like most Iraqi Jews, Yusef was indifferent to Zionism. In the family, this political ideology was considered “an Ashkenazi thing”.

Events beyond his purview (about which more later) projected his family and then him, largely out of the sense of responsibility, in the fledgling Zionist state. Even though he was to live over two decades in Israel, he and his Arab-Jew identity were irrevocably broken. He felt like a fish out of water, remained alien, unemployed and unaccustomed to the Ashkenazi-dominated society. But he never compromised his sense of humility, self-respect, and decency, never complained or asked for favours. The fate of this noble man illustrates that of many non-Ashkenazi Jews brought to Israel unaware of what awaited them in “the Promised Land”.

The uprooting of Iraq’s Jewish community is the leitmotif of the entire book. The Zionist colony, established by and for European Jews to solve Europe’s “Jewish problem”, needed Jews.

The natural reservoir of “human material” (as Ben-Gurion used to repeat) was severely depleted due to the Nazi genocide. Zionist emissaries were sent to Muslim-majority countries to bring in living souls, even though these communities had played almost no role in the Zionist movement.

The emissaries tried to convince, and, when this failed, cajoled and terrorized Jews. At the same time, arrangements were made, and bribes paid, to local officials who either facilitated emigration of Jews or looked the other way when they were smuggled out. The author, a witness, a victim, but also an eminent historian, painstakingly reconstructs the devastation of the Jewish community in Iraq, including Zionists’ acts of terror against Jews.

The author candidly recounts the intimate story of his family, profoundly traumatized by a fallout from Israel’s unilateral declaration of independence.

It triggered a war since it was against the will of the majority in Palestine and all the Arab countries that the British ruled Zionist colony was turned into a state for the Jews. Albeit landed in Israel in relatively comfortable circumstances (thanks to his father’s illicit transfers of money from Iraq), Avi as a child experienced humiliation and discrimination like all Mizrahi population in Israel. His self-worth was severely undermined, he barely passed from one grade to the next, and the Zionist society saw in this underachievement a proof of his “primitive” background.

What saved him and turned him eventually into an Oxford don was departure from Israel and the warm welcome he enjoyed from Jews in England. It is striking that this articulated and nuanced memoir was written by someone who consistently failed in the English language at the Israeli school. No less striking is the contrast between the rough Zionist culture of the muscular New Hebrew Men forged to fight wars and the culture of genteel and caring British Jewish culture he encountered, which preserved, whatever its vicarious Zionism, the Judaic values of mercy, modesty and beneficence codified in the Mishna.

Growing up in Israel and serving in its military, Avi naturally imbibed nationalist myths and became an almost typical right-wing Mizrahi. He deftly depicts his personal evolution from a self-righteous partisan of Zionist ethnocracy to a thoughtful proponent of a democratic state for all the inhabitants between the River Jordan and the Mediterranean.

Moreover, the author hopes that the collective memory of the centuries-long Arab-Jewish social and cultural integration should enable such a project to come true.

In this case, the heritage of Iraqi, Moroccan and other non-European Jews will be not only rehabilitated, but also put to good use to build a peaceful future.

It is hard to share this hope after months of unprecedented violence that has left tens of thousands dead and wounded. Yet, colonial regimes often become particularly violent before their demise. The Zionist ethnocracy, however unique, may face the same fate and open the way to a more equitable and therefore more humane political and social entity.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share button above. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

This article was originally published on the author’s blogsite, yakovrabkin.ca.

Yakov M. Rabkin is Professor Emeritus of History at the Université of Montréal. His publications include over 300 articles and a few books: Science between Superpowers, A Threat from Within: a Century of Jewish Opposition to Zionism, What is Modern Israel?, Demodernization: A Future in the Past and Judaïsme, islam et modernité. He did consulting work for, inter alia, OECD, NATO, UNESCO and the World Bank. E-mail: [email protected]. Website: www.yakovrabkin.ca