Spanish Judge Accused of Establishing the History of Atrocities committed by the Franco Dictatorship

“For the dead man here abandoned, build him a tomb.” Sophocles, Antigone (442 A.D.)

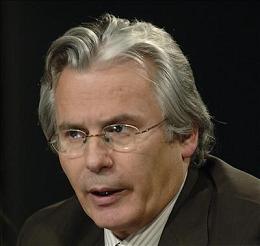

PARIS — “Senseless”, “astounding” , “unheard of” … The world press, human rights associations, and the finest international jurists can’t get over it. Why is the Spanish judicial system, which has done so much in recent years to punish and prevent crimes against humanity in many parts of the world, bringing charges against Baltasar Garzon, the judge who best symbolises the contemporary paradigm of applying universal justice?

The international media know well the merits of the “superjudge”: his transcendental role in the arrest of Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet in London in 1998; his denunciation of the atrocities committed by the military in Argentina, Guatemala, and by other Latin American dictatorships; his efforts to dismantle the GAL (Antiterrorist Liberation Groups, formed by the Spanish government to fight the ETA Basque separatists) and prosecute socialist premier Felipe Gonzalez; his opposition to the invasion of Iraq in 2003; and even his recent trip to Honduras to warn the coup participants that crimes against humanity are imprescriptible.

As a judge of the National Court of Spain, Garzon prosecuted thousands of activists of the terrorist Basque separatist group ETA (the right felt he should be considered for the Nobel Peace Prize). What generated criticism was his 1998 decision to order the closure of the Basque newspaper Egin, or his ordering of terrorism suspects to be held incommunicado. Organisations like the Committee for the Prevention of Torture of the Council of Europe have called for the abolition of this form of detention. Garzon’s immoderate appetite for the front pages and “superstar judge” behaviour are other targets of criticism.

In any case, Garzon has shown himself to be a rebel judge, independent and incorruptible. It is because of this that he has accumulated so many adversaries and now finds himself persecuted by those involved in “Gurtel[1]” matter and the heirs of Francoism.

There are in fact three charges pending against him in the Supreme Court, one regarding fees he received for conferences he spoke at in New York sponsored by Banco Santander. Another regards wiretaps ordered for the investigation of the “Gurtel” network. The main accusation involves the investigation of the crimes of Francoism.

Two ultraconservative organisations have accused him of “prevarication[2]” for having initiated in October 2008 an investigation into the disappearance during the Spanish Civil War of more than 100,000 republicans (whose bodies lie in unmarked ditches, denied a dignified burial) and the destiny of 30,000 children taken from their mothers in prison [3] and given to families on the side of the victors during the dictatorship (1939-1975).

If found guilty, Garzon will face a suspension of between ten and twenty years. This would be a great shame. Because at bottom this matter involves one central question: symbolically, what is to be done with the Spanish Civil War? The administrative decision taken in 1977 with the Amnesty Law (which in the short term was intended essentially to obtain the release from prison of a few hundred prisoners of the left) was not to do justice and not to impose any kind of policy with regard to memory.

Obviously 71 years from the end of the conflict, with all responsible parties deceased, the administration of justice cannot consist of physically trying those accused of abominable crimes. But this is not just a juridical matter. If it impassions millions of Spanish, it is because they feel that, beyond the Garzon case, what is at issue is the right of victims to moral reparation, the collective rights to memory and the possibility of officially establishing, on the basis of the atrocities committed, that Francoism was an abomination and that allowing it impunity is intolerable. It is essential to be able to say this, to proclaim it, and show it in “museums dedicated to the Civil War”, for example; in history textbooks; and on the solemn days of collective homage, etc. As is the case with all of Europe in solidarity with the victims of Nazism.

Proponents of the “culture of concealment” are accusing Garzon of wanting to open a Pandora’s box and divide the Spanish people again. They are insisting that the other side committed crimes as well. They have not understood the specificity of Francoism. They behave like a journalist who, seeking to organise a “fair debate” on World War Two, gave one minute to Hitler and one minute to the Jews.

Francoism was not just the war (in which General Queipo de Llano asserted, “We must sow terror and eliminate without scruples or wavering all those who don’t think like us.”) ; it was above all, between 1939 and 1975, one of the most implacable authoritarian regimes of the 20th century which used terror in a systematic manner to exterminate its ideological opponents and frighten the entire population. This is not a political assertion; it is a historical fact.

The Amnesty Law led to the imposition, on the Francoist “banality of evil”, of a sort of official amnesia, or a mechanism of “unconscious blindness” (collective, in this case) by which a person makes unpleasant areas of his memory disappear. Until the day they boil back up to the surface in an fever of irrationality.

This what judge Garzon wanted to avoid. He wanted to reveal the malevolent nature of Francoism so that history would never repeat itself. Never.

Ignacio Ramonet is editor of “Le Monde diplomatique in Spanish”.

Notes

[1] This involves figures in the rightist Popular Party (PP), particularly the ex-treasurer of the PP, Luis Barcenas.

[2] Prevarication is the issuance of a resolution by an official who is aware that the resolution is unjust.

[3] Ricard Vinyes Irredentas, Political Prisoners and their Children in the Prisons under Franco, Planeta, Barcelona, 2002. See the documentary Els nens perduts del franquisme (The Lost Children of Francoism) by Montserrat Armengou and Ricard Belis.