South Africa: The Fall and Rise (and Fall?) of Apartheid

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

Visit and follow us on Instagram at @crg_globalresearch.

***

Apartheid in South Africa ended in part due to sanctions and pressure from the international community. It is once again on the international community to ensure that international law is upheld and apartheid sees its demise, this time in Palestine.

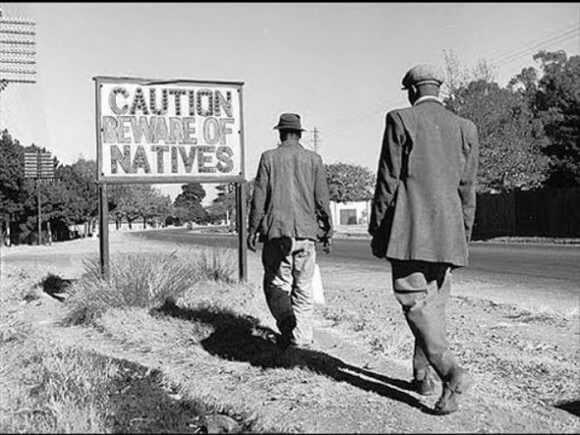

The vast majority of people today look back on the apartheid era in South Africa – 1948-1990 – with disdain and horror. Condemnation of the injustices under apartheid is, today, unequivocal; however, apartheid practices in Israel today are, despite the work of many human rights organizations and activists, still considered controversial or even debatable in the mainstream. Thus, it is critical to understand what apartheid is, its implementation in South Africa, and what helped to end it. The comparison is not to say that the systems were identical, despite many similarities, but rather to show how each falls under the definition of the crime of apartheid.

Apartheid is a system of separation in which “inhuman acts [are] committed for the purpose of establishing and maintaining domination by one racial group of persons over any other racial group of persons and systematically oppressing them.” (Article II, International Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid) In South Africa, the system of apartheid was entrenched through a series of laws and measures that ensured that ‘races’ – Whites, Blacks, and Coloreds – were not only separate, but that non-whites were denied basic rights, and whites were privileged in every sphere. Marriages and sexual relations, for example, between whites and other races were banned. Land Acts ensured that over 80 percent of the country’s land was set aside for its minority white citizens. The government also passed the Bantu Homelands Citizenship Act of 1970 – Bantustans were enclaves for black south Africans separated by tribe to ensure that blacks did not make up a majority – which stripped black South Africans of their citizenship. They were declared citizens of the respective Bantustans, depriving them of what remained of their rights in South Africa proper. From 1961 to 1994, more than 3.5 million people were forcibly removed from their homes and deposited in these Bantustans. The Bantusans were deemed separate homelands for black South Africans, entrenching the system of separation and differentiation. Permits were required in order to leave the Bantustans and enter a ‘white’ area or that designated for another race.

The penalties for violating these laws were severe, including fines, imprisonment and whippings. In addition to the legal system, murders of anti-Apartheid activists, media censorship, and torture were routine. Perhaps most notoriously, in 1960, police fired on an unarmed group of blacks South Africans and killed over 67, wounding 180. This was the infamous Sharpeville massacre. While the African National Congress, under Nelson Mandela, had previously advocated for non-violent resistance, the massacre led to the forming of a paramilitary wing to engage in guerilla warfare against the apartheid government. Mandela was arrested several times between 1961 and 1964, eventually being sentenced to life in prison in 1964.

The international community was not unaware of what was happening. Apartheid was annually condemned by the General Assembly from 1952 until 1990; it was also regularly condemned by the Security Council after 1960. In 1962, the General Assembly adopting a resolution requesting member states to break diplomatic, trade and transport relations with South Africa, and again in 1968 they requested the suspension of all cultural, educational and sporting exchanges, all in an effort to pressure South Africa to repeal its apartheid laws. In 1966, the General Assembly labelled apartheid as a crime against humanity, and in 1973, the Apartheid Convention was adopted by the General Assembly, declaring apartheid to be an international crime. Only four states voted against the Convention: Portugal, South Africa, the United Kingdom and the United States. There are currently 109 state parties to the Convention.

How, then, was apartheid alive and well from 1948 to 1990 – a full 42 years?

South Africa was important to certain States both strategically and financially. Strategically, as this coincided with the Cold War era, South Africa capitalized on the Western fear of communism, and held up its role as part of the Western alliance against communism. Financially, South Africa was the source of important commodities, namely gold and coal, and it was also a market for Western products.

Additionally, the South African government engaged in an international media propaganda campaign, setting aside some tens of millions of dollars to buy international media influence, including the launch of an English-language, pro-apartheid publication, called the Citizen.

Apartheid in South Africa

How did apartheid eventually end?

Despite these efforts, most international media outlets were unconvinced, and indeed, extremely critical of the actions of the apartheid government. There were also some watershed moments: in addition to the arrest of Mandela, the 1976 Soweto Uprising, and the subsequent arrest and tragic death of the South African activist, Steve Biko, caused further shift in global public opinion.

In 1976, inspired by Steve Biko’s Black Consciousness Movement, thousands of black South African students protested the forced use of Afrikaans in their schools. They marched peacefully, eventually approaching police barricades, and some threw stones at the police. Police opened fire at the unarmed youth and sprayed them with tear gas – the riots that ensued resulted in the killing of more than 661 people, the vast majority black. While there were attempts to censor the media, the incident was reported worldwide. Steve Biko and other Black Consciousness leaders were arrested. Biko died in prison, with evidence of torture that the South African government tried to conceal, and indeed harass journalists from disclosing.

It was in this year that the UN Security Council finally voted to impose a mandatory embargo on the sale of arms to South Africa. In 1985, the United Kingdom and United States imposed their own economic sanctions on the country, despite either voting against or abstaining from voting on imposing sanctions on South Africa in the 1960s. In 1985, the Security Council called on member states to pass more extensive economic measures against South Africa (however, in 1988, the UK and USA vetoed a draft resolution of selective sanctions).

South Africa was becoming increasingly isolated on the global stage, and attempted to repeal some apartheid laws in the mid 1980s, as well as conditionally release Nelson Mandela. However, most of the apartheid regime structure was to remain intact, with black South Africans largely excluded. This led to further demonstrations, which were met with more violence from the state. Eventually, F.W. de Klerk, the new Prime Minister in 1989, met with the previously banned ANC, and in February of 1990, Mandela was released. Apartheid eventually fell in 1990, with the writing up of a new constitution.

Why does all of this matter now?

Violence by the state, forcible displacement, denationalization, a system of IDs that determines access, land being made available only to one group of citizens, dispossession of an entire people, and separation based on race are all considered unequivocally reprehensible today. Yet this is exactly what is happening in present-day Israel and the occupied Palestinian territory. The Israeli government is currently in control of the whole area that was historic Palestine, and has instated a different regime for each area. Yet all the policies are designed to ensure the domination of one group – Jewish Israelis – over another group – Palestinian Arabs. In April 2021, Human Rights Watch released a report detailing the policies and practices that amount to the international crimes of persecution and apartheid. This is not new to Palestinian human rights activists and scholars, who have been sounding the alarm for decades. It is worth seeing the parallels between South African apartheid and the apartheid in Palestine-Israel today.

To see these parallels, we must return to 1948. In May of that year, the newly created state of Israel was in control of 77% of what was historic Palestine – much more than what the UN Partition Plan had allocated for the Jewish State. With the creation of the Israeli state, over 750,000 indigenous Palestinians were forcibly displaced from their homes and prevented from returning. As citizens and habitual residents of Mandate Palestine, these Palestinian refugees were entitled to return and indeed automatically be considered citizens of Israel under the laws of state succession. Yet Israel barred their return, eventually passing the 1952 Nationality Act, which denationalized the refugees. At the same time, Jews from all over the world were entitled to immigrate to Israel and obtain Israeli citizenship. This was to ensure a Jewish majority. Israel then passed a series of elaborate laws for the purpose of confiscating all private property of the 1948 refugees in order to give Jews almost exclusive access to it. Jewish immigrants were settled in the houses and on the lands of displaced Palestinians.

Palestinians who were able to remain – some 150,000 – were kept under military rule until well into the 1960s, preventing them from leaving the area they were in except with permits. The same laws used to confiscate the land of the Palestinian refugees was used to expropriate the property of internally displaced Palestinians who were to become citizens of Israel. It is estimated that between 40 to 60 percent of the land that belonged to internally displaced Palestinians – it must be emphasized, citizens of Israel – was confiscated, and Palestinian citizens of Israel today are still restricted from accessing land that was confiscated from them. Indeed, Israeli law allows towns to bar certain prospective residents due to claimed incompatibility, which largely affects Palestinian citizens. This discrimination is not simply with regards to land and residency rights. For example, the 2003 Citizenship and Entry into Israel Law (Temporary Order) bars granting Israeli citizenship or long-term legal status to Palestinians from the West Bank and Gaza who marry Israeli citizens or residents. This affects Palestinian citizens of Israel almost exclusively, since they are more likely to marry a Palestinian from the West Bank or Gaza. However, any other non-Jewish foreign national married to an Israeli citizen may be eligible for citizenship. These policies are engineered to ensure the domination of Jewish Israelis.

In 1967, Israel occupied the West Bank and Gaza. By the end of July 1967, the UN estimated that there were more than 200,000 refugees in Jordan; only 14,000 were allowed to return. Despite condemnation by the Security Council and the affirmation of the principle of the inadmissibility of gaining territory by war, Israel sought to alter the landscape of both the West Bank and Gaza, and officially annexed East Jerusalem. It began to construct Jewish only settlements in both the West Bank and Gaza, expropriating property and expelling Palestinians from their homes. In the West Bank today, Israel subjects Palestinians to military law, while civilian law is applied to the illegal settlements made exclusively for Israeli Jewish settlers. Land is also expropriated to make Jewish-only bypass roads. These illegal settlements are built on Palestinian territory and violate the Fourth Geneva Convention. Palestinians are largely prohibited from these settlements, entrenching this division and dispossession, while being denied building permits where they reside. Through various means, including house demolitions, deportations, evictions, and general reasons related to conflict, over 800,000 Palestinians have been forcibly displaced since 1967.

In East Jerusalem, a different legal regime exists under Israeli law because Israel considers East Jerusalem, in contravention of international law, as part of Israel proper. Israel thus considers the indigenous Palestinians who have resided there for generations as ‘residents’ – similar to other foreign nationals – making their legal status conditional upon different factors not required of Jewish Israelis. Hence, this results in forced evictions, denial of building permits, and revocation of residency. Over 14,000 Palestinians have had their residency revoked since 1967, which is also a violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention.

This is separate from the blockade imposed on Gaza since 2007. Israeli ‘disengaged’ from Gaza in 2005, removing settlers from the Gaza Strip for demographic reasons, but is still considered the occupying power as they maintain effective control over the entire area, deciding what can and cannot be imported, and how much of their territorial sea Gazan fishermen have access to (less than a third). Almost two million people live in the Gaza Strip and half the population are children under the age of 18. Due to the blockade, 90-95% of water in Gaza is unfit for drinking, and there are changing restrictions on a vast range of imports, including basic construction material. When Gaza is subject to attacks by Israel and buildings are destroyed, these cannot be rebuilt due to the import restrictions.

While this is simply a brief overview of the different laws and practices in place, the parallels are clear: Israel, which is in control of the whole of what was Mandate Palestine, has enacted different legal regimes that are all intended for a main overarching purpose: the division, dispossession and displacement of the Palestinians, and the privileging and domination of Jews.

The General Assembly has adopted resolutions every year since 1948 calling for “A just resolution of the problem of Palestine refugees in conformity with its resolution 194 (III)of 11 December 1948”, and since 1967, “The withdrawal of Israel from the Palestinian territory occupied since 1967, including East Jerusalem”, both of which Israel flagrantly ignores. The Security Council has also adopted a series of resolutions calling upon Israel to abide by the Fourth Geneva Convention, affirming the principle of the inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory by war, and condemning settlement activity, among others.

At the same time, the Security Council, due to vetoes by the United States, has never imposed sanctions on Israel, despite clear violations of international law over the decades. The international media, particularly in the US, has largely sided with Israel – with a few recent exceptions – attempting to equalize the dominant nuclear military power with a dispossessed and occupied people.

With the current events in Sheikh Jarrah, the al-Aqsa Mosque, and Gaza, people around the world are witnessing events in real time. Despite some attempts at censorship on social media, the mounting evidence is hard to ignore. It is on the international community to ensure that international law is upheld and apartheid once again sees its demise.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram, @crg_globalresearch. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Jinan Bastaki is a legal scholar and academic specializing in international law, human rights, and refugee law.