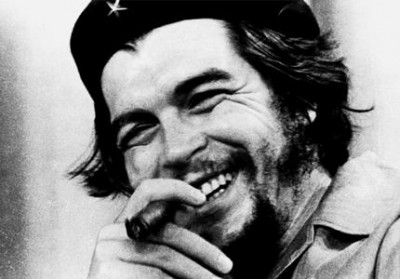

Solidarity as a Weapon against US Imperialism. Che Guevara

David Cameron worries about “swarms” entering the UK. Swarms are clouds of insects. Cameron should know migrants from Syria, Iraq, and Libya are people. Yet solidarity is not fellow-feeling. It involves recognition. And recognition is not individual, or even social. It depends upon networks of beliefs and practises – social, economic, cultural and political.

It is significant that Brazilian educator, Paulo Freire, wrote that liberation of the oppressed depends upon naming. He knew how difficult this is. So did Che Guevara. Guevara’s remarks about solidarity are relevant. Cameron’s uninteresting error deflects from the real challenge of the migrant crisis.

Guevara describes solidarity as readiness to die. His point is, in part, that solidarity involves sacrifice, even transformation. Solidarity, he warned, “has something of the bitter irony of the plebeians cheering on the gladiators in the Roman circus”. It is not enough “to wish the victim success”; instead, “one must share his or her fate. One must join the victim in victory or death”.[i]

Some won’t like mention of death. In North America, we practise “pathological upbeatness”[ii], believing in (our own) survival no matter what. Antonio Gramsci called such an attitude lazy. One allows one’s understanding of reality to be “burned at some sacred alter of enthusiasm”. Such optimism, he wrote, is “nothing but a way to defend one’s own laziness, irresponsibility and unwillingness” to see things as they are.

But seeing how things are depends also upon circumstances and conditions. It is not merely intellectual. Whether migrants are “swarms” or people is not, more interestingly, about language or philosophy. It is not mainly about human rights. Brazilian philosopher, Frei Betto, notes that “the mediation of philosophy doesn’t suffice for understanding the political and structural reason for the massive existence of the non- person”.

This was clear to Guevara. If one is “cheering on the gladiators”, one has little effect. Worse, though, without transforming relevant institutions, including ways of thinking, there may be no victims with whom to be in solidarity. Without challenging imperialism, including its unworkable vision of how to live, no people will be in the ring. They will not be identifiable as such. They are “non- persons”, who don’t count.

When Fidel Castro spoke to the United Nations in 1960, he invited the audience to imagine “that a person from outer space were to come to this assembly, someone who had read neither the Communist Manifesto of Karl Marx nor UPI or AP dispatches or any other monopoly controlled publication. If he were to ask how the world was divided up and he saw on a map that the wealth was divided among the monopolies of four or five countries, he would say, ‘The world has been badly divided up’”.

The point is not that the world is badly divided up. The truth of that claim is obvious. But it is hard to give it importance. It is hard to see that it matters to how we think about the world and the people in it, including ourselves. The message to the UN is that a visitor from outer space— someone whose understanding arises from different circumstances and conditions — might see such empirical data as important, even urgent.

Or they may not. Italian journalist Gianni Minà notes that it is not surprising that the rich  minority see no evil in a global system in which so many se nace para morir (are born to die). But he identifies a “grotesque logic” that makes it surprising that four- fifths of the world’s population, having lost their resources to the richest fifth, try to enter our borders for a chance at survival.

minority see no evil in a global system in which so many se nace para morir (are born to die). But he identifies a “grotesque logic” that makes it surprising that four- fifths of the world’s population, having lost their resources to the richest fifth, try to enter our borders for a chance at survival.

Solidarity is a tool for exposing such logic. Speaking to medical workers in 1960, Guevara advised:

“If we all use the new weapon of solidarity … then the only thing left for us is to know the daily stretch of the road and to take it. Nobody can point out that stretch … in the personal road of each individual; it is what he will do every day, what he will gain from his individual experience”.

“What he will do every day”. Guevara was a dialectical materialist, a naturalist, recognizing cause and effect. He saw human freedom as depending upon the “close dialectical unity” existing between people moving collaboratively in a definite direction. It is how we grow because it is how we know. It is a process of transformation, sometimes resulting in “el hombre nuevo” (the new person), who is able to understand better, from a more adequate perspective.

Contemporary feminists often agree. Intellectual understanding is limited by availability of concepts, including self-concepts. We cannot understand what we cannot name, at least not fully. Therefore, we must, occasionally, be moved by feelings, in the body, in order to know. Feelings can create interest, motivating discovery. Thus, for Guevara, true revolutionaries possess “great feelings of love”. They recognize human beings who are unnamed.

Guevara is criticized for urging armed struggle. (Although his daughter, Aleida, says that if her dad were alive, he’d be a techie, organizing on the internet, fascinated by computers.[iii]).But Guevara and Freire deliver a more threatening message. Freire argued that it is impossible that the direction toward “recovery of the people’s stolen humanity” not be detectable. Perhaps, possibilities for “authentic humanity … must simply be felt— sometimes not even that”. But they exist and are discoverable. They can be named through “unity, organization and struggle”.

The challenge is that if authentic humanity can be named, so also can the inauthentic. And it may be what we are living. Of course, we don’t believe in authentic humanity in North America, so we are saved. As Alan Ehrenhalt writes, we believe in choice, the more the better. Happiness is not authentic or inauthentic. It is whatever we choose it to be. Humanism, if it even exists, is known “from the inside”.

In contrast, Guevara, Freire, Simón Bolívar, José Martí, Frantz Fanon, and José Carlos Mariátequi knew “the tiger [of imperialism] waits behind every tree, crouches in every corner”.[iv] They had to ask how to know authentic humanity. And they knew living from the inside does not give the right answer. It does not include Latin Americans, already disqualified. Mariátequi, instead, insisted that indigenous traditions replace “Eurocentric thought”: “Life comes from the earth and returns to the earth”. Thus, it must be known “from the earth”, through engagement, not through self-absorption and introspection.

Guevara’s remarks on solidarity do not set him apart from other (mostly non-European) philosophers. The ancient Chinese philosopher Chuang Tzu (fourth century BC) maintained that to lose one’s life is to save it and to seek to save it for one’s own sake is to lose it. Eastern philosophers in particular understood attachment to self, and obsession with security, to constitute the most radical form of alienation. One cannot know others that way, at least not most others. Even worse, one risks not knowing they are there to be known.

When BBC reporter Iain Bruce researched the Chávez revolution, he noted Venezuelans’ frequent use of the word surgir (to emerge, to spring forth). Venezuelans in the barrios described wanting to emerge. And indeed, a whole section of Venezuelan society, “millions of people who had been buried in silence, obscurity and neglect, have suddenly ‘emerged’ from the shadows and established themselves as actors, as protagonists both of their own individual stories and of the nation’s collective drama.”[v]

According to Bolivian president Evo Morales, “If we want to defend humanity, we must change the system, and this means overthrowing US imperialism.” But it is not just about the oppressed. At the first International Writers’ Congress for the Defense of Culture in 1935, Bertolt Brecht suggested that when someone falls down, other people faint, but if violence falls like rain, people turn away when others suffer. The issue was naming fascism. If violence is everywhere, falling like rain, it is not violence.

Springing forth, for Guevara at least, is what it means to be human, an implication of our real circumstances, within nature. We know the world, and the people in it, by changing the world, and being changed ourselves. Living from the inside, as we cheer the gladiators, we risk not knowing what we are cheering. We won’t see that violence is falling like rain.

There are better reasons to be upbeat than believing in ourselves. The “sacred alter of enthusiasm” could be better defined if we looked South. It is not just about seeing how the world divides up, and understanding the implications. It is also about authenticity in what Charles Taylor calls the “age of authenticity”, which may be false. Guevara’s remarks on solidarity are part of a bigger project; the human condition. It is not a radical view. And its merits can be known, by living. But the need for such a view must also be named. It may take “unity, organization and struggle”.

Nobel-prize-winning author, Gabriel García Márquez, noticed in Cuba “the near mystical conviction that the greatest achievement of the human being is the proper formation of conscience”. Guevara is part of the legacy. He saw moral, not material incentives driving the world forward, meaning by “moral” the broader, more interesting sense of experiencing humanness. This means that it is not virtuous to pursue solidarity but practical. At least, this is so if one acknowledges the “plain and practical scientific reality”[vi] of human interdependence.

The Second Declaration of Havana in 1962 states that “Cuba and Latin America are part of … the struggle of the subjugated people; the clash between the world that is dying and the world that is being born”. It is still the case. Cuba, Venezuela, Bolivia, and Ecuador have in recent years, as the Second Declaration describes, “pointed out the danger hovering over America and called it by its name: imperialism”. They have also named its consequences: a mistaken and damaging conception of human well-being. It hovers over all of us.

Susan Babbitt is associate professor of philosophy at Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada and author of José Martí, Ernesto “Che” Guevara and Global Development Ethics: The Battle for Ideas (Palgrave MacMillan 2014).

Notes

[i] Guevara, Che.”Create two, three, many Vietnams”, David Deutschman (Ed.), The Che Guevara reader (New York: Ocean Press, 1997) 316

[ii] Terry Eagleton, Reason, faith and revolution (Yale University Press, 2009) 138

[iii] Speaking at Kingston Collegiate Vocational Institute, Kingston, Canada, Sept. 30, 2003.

[iv] Martí, José “Our America”. In Esther Allen (Ed. and Trans.), José Martí: Selected

writings (New York: Penguin Books, 2002) 293

[v] Bruce, Iain. The real Venezuela: Making socialism in the 21st century (London: Pluto Press, 2008) 22.

[vi] Martí, “Wandering teachers” In Deborah Shnookal & Mirta Muñez (Eds.), José Martí Reader: Writings on the Americas (New York: Ocean Books) 47.