“Soft Power”: Americans in Its Grip at Home Must Face the Mischief It Wields

I suspect most Americans would approve of what they understand to be this nation’s global cultural reach as expressed through its ‘soft power’. A term coined by an American political scientist, soft power “involves shaping the preferences of others through appeal and attraction”. Contrasted with coercive measures, it’s achieved largely through cultural means, although nevertheless a feature of foreign policy. Probably as old as politics itself.

Soft power politics are long-term, sociable and gentle. (Certainly nothing dangerous!) To say that they’re ideologically driven would be guileless. Some definitions are less circumspect, describing soft power as “using positive attraction and persuasion to achieve foreign policy objectives”. When at work domestically, it may be akin to kneeling-softly-on-the-neck, persuading Americans how this is a land of equality and unparalleled freedom.

U.S. citizens may even consider America’s soft power abroad with pride: “This is how we’re helping others– securing democratic principles, sharing advanced (sic) intellectual, medical and cultural resources. American films, so popular (and lucrative) globally, augmented by satellite-enabled news and entertainment channels are, I would argue, among the most effective examples of this power. Music and literature cannot be excluded too.

Boosting commercially-driven exports are government-funded programs like Peace Corps, high school scholarships, youth exchanges, anthropological research and conferences. All proceed at an undiminished pace, whichever party rules. These programs also carry that ‘cold light of reason’ imparted to foreign peoples held to be short on ‘objectivity’ or ‘reason’. Implicit in this largesse is an intellectual and aesthetic superiority on the part of the donor.

Globally, tens of millions indiscriminately embrace soft power projects originating in European (white) nations. They search them out and compete for any awards offered. Soft power programs can foster the belief in people that their own government is evil, hopeless— at least uncaring — leading such romantics to conclude it should be overthrown– if not internally, then by an invading force. They feel they are a doomed, emotional people unable to advance as long as they live in the smothering atmosphere of ‘tradition’ and of ‘tribalism’. To escape they must remodel their hair, learn to wear neckties and speak correctly, eat with a fork and acquire quality foreign accoutrements—from mountain bikes, Cuisinart toasters and Victoria’s Secret underwear, to Boeing fighter jets.

Let’s face it: that cultural bounty and the fabulous stuff associated with it is propaganda. Originator of the term soft power, Joseph Nye, admits “the best propaganda is not propaganda”.

What’s propaganda and what’s not is an ongoing debate. Leading American critics of imperialism as it’s dispensed via soft power include Edward Said, Malcolm X and Cornel West. They join generations of intellectuals and dissenters warning of its hazards. Across the world the destructive impact of that soft power is not wholly unopposed. Political prisoners and martyrs, armed rebels—women and men engage in the eternal struggle to lift off the imperial “knee on their neck”—both its soft and coercive iterations.

That oppressive “knee on their neck” has become the symbol of the American police state, manifest so compellingly and undeniably in the famous video of George Floyd’s murder.

America’s Black, Brown and Native populations are familiar with the brute force of that killer knee. They equally recognize the effectiveness of the knee’s soft power (unnoticed by others) in maintaining the status quo. The soft knee works into centuries of renegotiated treaties, temporary fixes, pleas for more time; it resists reform; it offers gratuitous sympathy, compromises and inclusion programs. Soft power is powerfully seductive, reinforced among all classes by a steady diet of Hollywood’s white savior tropes.

Often people are mollified by small gains and minor adjustments. Many become weary; they simply surrender. She learns to hold her breath, turn her eyes down and rush away to weep and scream in private. Daughter removes her head covering; brother marries out of his faith, shaves his beard; mother joins a temple or mosque.

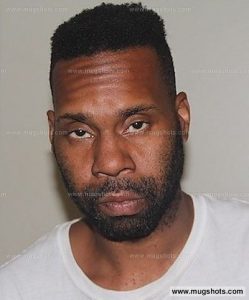

Demanding real change is very risky. In 2016, a short-lived event although less dramatic than the removal of an inglorious military statue poignantly carries the weight of America’s soft-power-enforced history. Corey Menafee (image on the right), a longtime kitchen employee at Yale University regularly passed under an image, a stained glass window (see image below) which others, if they even noticed it, may have viewed as inconsequential, a quaint reference to the distant past. But Menafee’s ire rose each time he thought about it. He may have vowed to either leave his job or formally appeal for the image’s removal. To Menafee, it was a symbol of his enslaved ancestors and a romanticization of America’s crime of racism. That image of Black women cotton pickers reminded this man of the exploitation of his people: — a crime neither recognized, nor seen, nor felt by others.

Surely knowing it would cost him dearly Menafee made a courageous decision: he smashed the window. That supreme act may seem reckless but to this Black American– to anyone who knows the insult that that image speaks and the risk involved in challenging it– it’s a big deal, a very big deal.

This kind of protest, a mark of the Black American movement’s mission, compels us to recognize the seemingly innocuous effect of the soft power we inhale every day. That unchallenged window in a reputedly liberal university suggested that there’s no political implication there; it’s just art, just culture, decorative and hardly noteworthy.

To Black Americans it is an agonizing image, one of millions existing across our cultural and linguistic landscape. It’s more egregious, the rising call to action more urgent, because whites do not perceive their racial implications. That window remained embedded in the wall, year after year, generation after generation, seen by thousands of smart (sic) people while its hurtful and humiliating power went unopposed.

Al Sharpton, in his peerless eulogy at George Floyd’s memorial in Minneapolis, helped define American history for us this way:

“George Floyd’s story has been the story of black folks because ever since 401 years ago, the reason we could never be who we wanted and dreamed to being is you kept your knee on our neck. We were smarter than the underfunded schools you put us in, but you had your knee on our neck. We could run corporations and not hustle in the street, but you had your knee on our neck. We had creative skills, we could do whatever anybody else could do, but we couldn’t get your knee off our neck. What happened to Floyd happens every day in this country, in education, in health services, and in every area of American life, it’s time for us to stand up in George’s name and say get your knee off our necks. That’s the problem no matter who you are. We thought maybe we had […], maybe it was just us, but even blacks that broke through, you kept your knee on that neck. Michael Jordan won all of these championships, and you kept digging for mess because you got to put a knee on our neck. White housewives would run home to see a black woman on TV named Oprah Winfrey and you messed with her because you just can’t take your knee off our neck. A man comes out of a single parent home, educates himself and rises up and becomes the President of the United States and you ask him for his birth certificate because you can’t take your knee off our neck. The reason why we are marching all over the world is we were like George, we couldn’t breathe, not because there was something wrong with our lungs, but that you wouldn’t take your knee off our neck. We don’t want no favors, just get up off of us and we can be and do whatever we can be.”

That knee on the neck is more than a physical force. It’s the cultural conditioning, the light of cold reason, the deflection, the imbibed message that Blacks are not quite up to the arbitrary standard set and maintained within soft (white) power. That folksy depiction of women in the cotton field is simply a pleasing piece of art. The slave supporting the warrior that crowns a national museum is just an aesthetic compliment to its central (white) figure! African and Muslim headwear is impractical. Lungi wraps on men are unprofessional. And on and on.

Soft power is so dominant and simultaneously appears so innocuous, so embedded and integrated into white privilege and white’s assumptions of their dominant historical place, that they fail to see its propaganda. It also works on newcomers, notably Asian and Arab immigrants, who buy into the American dream. Having absorbed a steady diet of soft power in their homelands, they easily sanction and join the American status quo.

(Anthropologists–and I am one– are slow to admit our role in advancing the soft power of imperialism. After all, anthropology itself emerged hand-in-hand with the expansion of European imperial rule. We might do better to turn our analytical skills to exposing the soft-knee-on-the neck and vigorously work to demolish it.)

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

B. Nimri Aziz is an anthropologist and journalist who’s worked in Nepal since 1970, and published widely on peoples of the Himalayas. A new book on Nepali rebel women is forthcoming.

All images in this article are from the author