Six Things You Should Know About the U.S. Nuclear Weapons Arsenal

If you think nuclear weapons went the way of the Berlin Wall and shoulder pads at the end of the 1980s, think again.

The U.S. still has a very large nuclear arsenal, and we’re considering spending quite a lot of money to update it. Based on our recent video conversation, we compiled a list of six things you should know about the nuclear arsenal.

If you’re not a millionaire (or billionaire, or trillionaire – just kidding, those doesn’t exist, at least not yet), numbers with a bunch of zeros after them can start to look the same.

But rest assured, $1 trillion is a lot of money, even—or especially—for our debt-laden federal government. Is it really a good idea to spend $1 trillion to update our arsenal? (That’s $1,000,000,000,000, in case you were wondering).

“We’re at a pivot point,” said Jim Walsh, a research associate in the Security Studies Program at MIT.

“These systems are showing their age. Decisions are going to have to be made over the next several years about what to do about that. Those decisions will have consequences for the future, and we should not just do it out of habit or autopilot—we really need to engage this, and engage it now in a strong way…This modernization is not simply life-extension. In some cases, we would be adding new capabilities we haven’t had before, and new weapons systems we haven’t had before.”

If we do decide to proceed with costs of up to $1 trillion over the next 30 years, many of these bills will be due around the same time. It’s important to take into consideration the opportunity cost of spending this amount of money on modernizing the nuclear arsenal.

“It’s been considered a budgetary train wreck, because we’re trying to modernize all of the legs of the nuclear triad (sea, air, and land) at the same time,” said Greg Terryn, a policy analyst at The Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation.

“The real concern there is either that you can’t finish a program you started and your nuclear arsenal changes based on budgetary constrictions, or that every dollar you spend on nuclear arsenal is money you’re not spending on your conventional forces or domestic needs. That means that troops in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, where we still have deployed forces and military operations, might not get the funding they need to complete their objectives.”

Nuclear-armed cruise missiles are considered by many nuclear policy experts to be particularly destabilizing. These weapons are launched without warning, and it’s impossible for the target to determine whether the weapon has a nuclear or conventional tip. Essentially, a recipe for disaster.

Yet despite these risks, the U.S. military is planning to build up to 1,100 new nuclear-capable cruise missiles. Former U.S. Secretary of Defense William Perry and former Assistant Secretary of Defense Andrew Weber wrote an Op-Ed in The Washington Post in October calling for President Obama to scrap this part of the plan.

“I believe in a safe, secure, and effective nuclear deterrent for the U.S.,” said Weber in Reinvent’s recent video conversation.

“I’m proud of some of the efforts that the Obama administration made to reverse decades of neglect in our nuclear arsenal. That said, I think we have some real opportunities moving forward to think more about types of nuclear weapons…Bill Perry and I would like President Obama, in his last year, to challenge the world, all of the nuclear weapons-possessors, to either forego or eliminate this particularly dangerous class of nuclear weapons.”

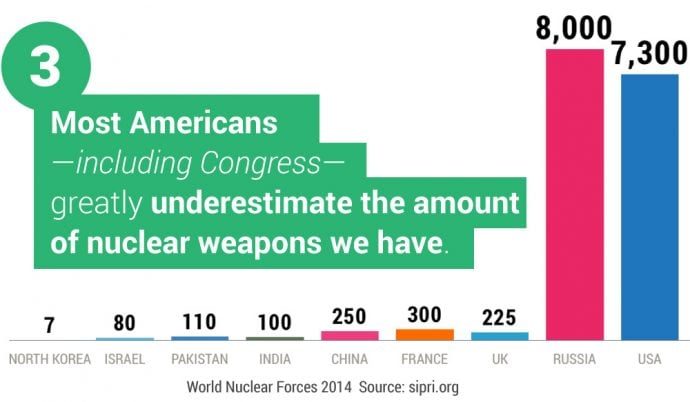

In 2013, advocacy organization Global Zero polled 70 members of Congress about the size of the U.S. nuclear weapons arsenal. Ninety-nine percent didn’t even get close to the correct number (which is more than 7,000). And in a 2004 poll, fewer than 20 percent of Americans guessed that we had more than 1,000 weapons.

“You need a groundswell of support from the constituencies in the United States in order to enact political change,” said Terryn.

“The challenge is that Millennials don’t think of nuclear weapons as a realistic concern right now. When I left policy school to come into the nuclear field and told my friends I would be working on nuclear weapons policy, they said, ‘We still have those?’…When people realize this is an existential threat, and maybe the biggest threat to human life we have, that can motivate political change.”

The perception that nuclear weapons are a 20th-century problem is a dangerous one, because it becomes much more difficult to gain enough momentum for substantive policy change.

“There is no real consciousness—particularly among young people, but really young and old alike, that we have as many nuclear weapons as we have, and that the dangers we face are not only from our enemies who have them, but from the weapons themselves,”

said Walsh.

Of the roughly 16,000 nuclear weapons in the world, around 93% are owned by the U.S. and Russia.

In 2012, then Senator and future Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel, Ambassador Thomas Pickering, and Vice Chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General James Cartwright, among others, signed a report advocating for a reduction of the nuclear arsenal to around 900 weapons.

“The world has changed, but the current arsenal carries the baggage of the cold war,” General Cartwright told The New York Times. “What is it we’re really trying to deter? Our current arsenal does not address the threats of the 21st century.” An approach to nuclear weapons policy that isn’t primarily focused on “keeping up” with other countries could help prevent potentially destabilizing arms racing and brinksmanship.

“I’d like to get away from the thinking that numerical values are the most important thing,” said Terryn.

“I’d like to focus more on strategic stability in a broader sense. That’s looking at the nuclear arsenal, but not just how many weapons we have—looking at variety, flexibility of the delivery systems, command and control, intelligence, conventional weapons, economic deterrents—taking that entire approach to strategic stability, instead of what we often see in the halls of Congress, which is, ‘Does Russia have one more nuclear weapon than we do, and does that mean we’re all going to die?’”

Members of the U.S. military called “missileers” sit underground and guard our intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) silos. Low morale among missileers, including cheating on nuclear training tests, has been a problem for decades, and can have potentially disastrous consequences. “Being a missileer means that your worst enemy is boredom,” one such missileer wrote in a 2011 article in Wired. “No battlefield heroism, no medals to be won. The duty is seen today as a dull anachronism.” (Another tidbit from the article: the missileers sitting underground right now, who hold the fate of the world in their hands, very well may be wearing Snuggies).

“Is this really a fixable problem?” asked Walsh. “We’ve had this for decades now, and it seems structural.” Mistakes among missileers often lead to more regulation and testing, Walsh said, which adds more pressure, thus leading to more failed tests and even lower morale.

“I think some of that is inevitable,” said Christine Parthemore, an international affairs fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations. Parthemore pointed out that while it’s difficult to trump the appeal of fields like cyber and space among newly enlisted servicemen and women, the Department of Defense continues to work towards boosting missileer morale and improving performance.

“A lot of the focus in the last two years in particular has been on how to take the pressure off these young men and women. Going back on the notion that testing them more and applying more and more pressure is the way to go…Taking some of the stress off while maintaining very high standards is a really hard thing to balance, but I think the department is trying.”

When it comes to nuclear weapons, the U.S. has gotten lucky more than once. While the military has made adjustments to procedures after accidents and mistakes, “accident” and “mistake” aren’t words you want associated with nuclear weapons in the first place.

“There was an instance [in 1980] in which a wrench was dropped in a silo. It detonated a missile and it actually flew off,” said Terryn. One airman died and 23 people were injured.

“After that, we stopped using liquid fuel. We had another instance [in 1961] in which a live nuclear weapon was dropped on North Carolina. Luckily it didn’t detonate. Three out of four of the failsafes failed but one worked, and that’s why we still have 50 states. After that, we stopped flying live alerts.”

Author of Command and Control (and past Reinvent roundtable participant) Eric Schlosser, who revealed North Carolina’s near-miss in 2013, estimates there were at least 700 accidents related to nuclear weapons between 1950 and 1968 alone.

Walsh reiterated the dual potential of these weapons: to protect and destroy. It’s like buying a handgun and keeping it in the bedroom for protection, Walsh said. The gun might enable you to protect yourself, but there are also risks to having a handgun in your home. In order to jumpstart a broader conversation about the pros and cons of modernization, it’s imperative that we elevate public consciousness about the inherent dangers of nuclear weapons.

“In this election season,” Walsh said, “we should be asking presidential candidates, Democratic and Republican alike, what their views are, and challenging them to explain why they think the choices they’re making will make us safer.”