Secret COINTELPRO Plot to Infiltrate and Destroy the American Indian Movement: “We Wanted Them to Kill Each Other”—FBI Agent Admits After Five Decades of Silence

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name (desktop version)

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

February 27 through May 8 marks the 50th anniversary of the occupation by the American Indian Movement (AIM) of Wounded Knee on the Oglala Lakota Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota, the site of the last great massacre of the Indian Wars in December 1890.

In a 2019 documentary that aired on PBS, From Wounded Knee to Standing Rock: A Reporter’s Journey, filmmaker Kevin McKiernan interviewed Tom Parker, an FBI agent working for the FBI’s counter-intelligence operation (COINTELPRO), who admitted that the FBI had helped to fracture and disrupt AIM during its 1973 Wounded Knee occupation.

“[W]e wanted them to kill each other, as we were in a war against AIM,” Parker said.

According to Parker, a main goal of COINTELPRO was to infiltrate informers into AIM and to publicly identify AIM activists with the FBI so that others in AIM would turn against them.

In this way, Parker said, dissension would grow among AIM, and AIM members would become paranoid about FBI infiltration and turn against one another, and there would be violence.

The Case of Annie Mae Aquash

One of the tragic victims of the FBI’s COINTELPRO operation was Annie Mae Aquash, a Micmaq from Nova Scotia and teacher who participated in the 1973 Wounded Knee occupation. She was murdered by two members of AIM in December 1975 at the age of 30 after the FBI and CIA had disseminated rumors that she was an AIM informant.

In March 2003, Arlo Looking Cloud and John Graham (also known as John Boy Patton) were indicted for Aquash’s murder and both were convicted and given long prison sentences.

Aquash’s family, including her two daughters, believe that higher-level AIM officials ordered her murder, fearing she was an FBI informant.

Some even suspected that AIM leader Dennis Banks (1937-2017) was involved, though the South Dakota district attorney’s office exonerated him.

FBI Agent David Price had made it a practice of befriending Aquash in public to give off the impression that she had become an informant.

This was part of the campaign to sow the seeds of distrust within AIM and have people in the group turn on one another. According to Parker, it was “in the realm of possibility that Annie Mae Aquash was killed in that way; and if she was, we [the FBI] weren’t concerned about it; like in a criminal situation, we wanted them to kill each other.”

AIM Founding and Goals

From Standing Rock to Wounded Knee includes original footage from the 1973 AIM occupation of Wounded Knee, which was triggered by the terrible living conditions on the Pine Ridge reservation and mistreatment of the Indian population.

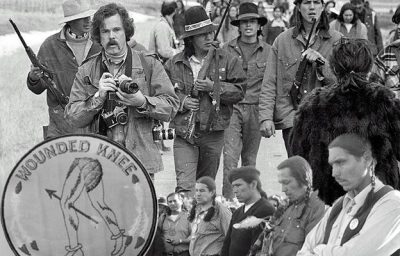

Filmmaker Kevin McKiernan during the occupation at Wounded Knee in 1973, with Lakota elders Oscar Bear Runner and Tom Bad Cob. [Source: listen.sdpb.org]

AIM had been founded in Minneapolis by Dennis Banks, Clyde Bellecourt, Eddie Benton Banai, and George Mitchell. Its original goal was to help Indians in urban ghettos who had been displaced by government programs that had the effect of forcing them from the reservations.

AIM subsequently expanded to promote economic independence, the revitalization of traditional culture, protection of legal rights and, most especially, autonomy over tribal areas and the restoration of lands that they believed had been illegally seized.

Source: northcountrypublicradio.org

War on AIM

After AIM occupied Wounded Knee, Richard Wilson, the head of the Oglala Sioux tribal council, declared a state of emergency and called in U.S. marshals to back him up.

A plumber by trade, Wilson had been a target of AIM, which accused him of the misappropriation of tribal funds and saw him as being too close to the whites.

He deployed his own private militia against AIM, called Guardians of the Oglala Nation (GOONs), which worked with the FBI and killed dozens of AIM activists and their supporters.

Most of the killings went unpunished as the homicide rate on the Pine Ridge reservation became among the highest in the U.S.

GOON leader Duane Brewer said that he “got along very well with the FBI,” which gave him ammunition to “do the job against AIM,” with whom the GOON’s were at war.

Among those killed was Brian DeSersa, a young Oglala AIM supporter who was shot at the wheel of his car in broad daylight.

One of AIM’s primary demands in leading the occupation of Wounded Knee was to overturn the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty, which had forced the Sioux to give up thousands of acres of land and to move to the Great Sioux reservation in the western half of South Dakota.

The signing of the treaty—between the United States, represented by General William T. Sherman, and the Sioux—in a tent at Fort Laramie, Wyoming, 1868. [Source: factsandhistory.com]

The Fort Laramie Treaty was violated when General George A. Custer, commander of the U.S. Army’s 7th Cavalry regiment, led an expedition into the Black Hills, accompanied by miners, seeking gold, and began attacking bands of Sioux hunting in accordance with their treaty rights.[1]

In April 1973 after several months of occupation, the Nixon administration said that it would revisit the Fort Laramie Treaty and adhere to AIM’s demands to keep old treaty rights alive.

Kent Frizzell, Nixon’s lead negotiator who was then U.S. Assistant Attorney General, even attended a pipe-smoking ceremony with Russell Means and other AIM leaders as a sign of peace.

Russell Means and Kent Frizzell shaking hands. [Source: history.com]

The agreement fell apart, however, as the Nixon administration claimed that it would not negotiate while AIM had guns pointed at federal officials.

The FBI and other federal agencies at this point laid siege to the Pine Ridge reservation, cutting off electricity and water. Gunfights ensued and the U.S. Army secretly began running military operations against AIM.

When anti-war protesters parachuted food to the residents of Pine Ridge, Army helicopters shot at the food and killed a member of AIM. AIM supporters fired back in kind. Phil Bautista, an Ojibwa Vietnam veteran, said that he loved shooting at government helicopters as it was a way of fighting back against the injustices done to his people over hundreds of years.

The Ordeal of Leonard Peltier

On May 8, 1973, AIM surrendered to federal authorities, ending the three-month occupation.

Many of the AIM leaders were subsequently killed by Wilson’s paramilitary GOON squad or prosecuted by the federal government, which aimed to tie up AIM in court cases while waging an effective counterinsurgency operation against it.

When two FBI agents were killed on the Pine Ridge reservation on June 26, 1975, the FBI fingered AIM leader Leonard Peltier, who was convicted and sentenced to life in prison.

However, one of the key witnesses at the trial, Myrtle Poor Bear, said that she had been coerced into signing a false affidavit implicating Peltier and that her life had been threatened. “They had the law in their hands, and could do anything,” she said of the FBI.

U.S. Lost, Indian People Won

Though AIM had been forced to end its occupation and its ranks were decimated, University of Colorado law professor Charles Wilkinson suggests that it was the U.S. that lost the second battle of Wounded Knee, and that it was Indian people who won.

This was because the AIM occupation of Wounded Knee raised public awareness about the injustices experienced by Native Americans and emboldened them to stand up for themselves and take pride in their culture.

Afterwards, a flurry of legislation supporting Indian rights was passed by Congress.

Key new laws included: a) the 1975 Indian Self-Determination and Educational Assistance Act, which committed greater federal funds to provide education and services to help Native American children to succeed; b) the 1978 American Indian Religious Freedom Act, which returned basic civil liberties to Native Americans by protecting their freedom to engage in traditional religious practices (which had been restricted in the past); and c) the 1978 Indian Child Welfare Act, which recognized the authiority of tribal courts to hear the adoption and guardian cases of Indian children.

In the early 21st century, many AIM veterans could be found working to revitalize their communities and helping to revive its cultural practices, with the threat of government violence receding.

From Wounded Knee to Standing Rock

From Wounded Knee to Standing Rock ends with footage from 2016 when the Standing Rock Sioux led large-scale protests against the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAP), which threatened the local water supply and was in violation of the Fort Laramie Treaty guaranteeing the undisturbed use of reservation lands.

Source: occupyworldwriters.org

Viewed positively by a significant percentage of the U.S. public, the DAP protests marked an important victory for the heirs of AIM.

The Biden administration, nevertheless, showed it was not so different from its predecessors when it failed to shut the DAP down while an environmental review demanded by the protesters and ordered by the Supreme Court was being conducted.

Biden was also carrying out brazenly imperialistic policies including the theft of land and resources around the world that are all too familiar to Native Americans.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Jeremy Kuzmarov is Managing Editor of CovertAction Magazine. He is the author of four books on U.S. foreign policy, including Obama’s Unending Wars (Clarity Press, 2019) and The Russians Are Coming, Again, with John Marciano (Monthly Review Press, 2018). He can be reached at: [email protected].

Note

-

In 1876, Custer, leading an Army detachment, encountered an encampment of Sioux and Cheyenne at the Little Bighorn River, and Custer’s detachment was annihilated. The Wounded Knee massacre was carried out in revenge by Custer’s old 7th Cavalry regiment.