Another Brewing Scandal: Saudi Arms Sales, the Ghost of a Reporter, and America’s Oil War in Yemen

The brutal killing of George Floyd by police, followed by the president’s calls for military intervention against protestors, are causing words like “dictatorship,” “authoritarianism,” and even “fascism” to become part of the national discourse. But the president has been dismantling constitutional safeguards for a long time, and the racism he and his administration have broadcast across the nation extends around the world, too.

In Iraq, where civilian populations have long suffered under the heel of American militarism, protesters applauded the demonstrations in American cities. In Yemen, now in its fifth year of a US-armed Saudi war that has decimated civilian populations, its desperately poor people are bracing for an onslaught of covid-19 due to cuts in UN assistance by Gulf countries allied with the US. But while this tragedy is going largely unnoticed, some key American lawmakers are trying to hold the Trump Administration — and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo in particular —accountable for mishandling the war in Yemen through illicit arms sales to Saudi Arabia.

A Congressional hearing on June 3rd focused on the abrupt firing last month of the man looking into the arms sales, the Inspector General charged with oversight of the State Department, including the secretary of state.

IG Steve Linick (image on the right), who accused Pompeo of misconduct, has become the latest victim in a string of politically motivated firings of government watchdogs. If the president’s bunker mentality isn’t disturbing enough, a deeper look into this scandal shows how racism lies at the heart of Trump’s and Pompeo’s foreign policy. And how oil, most notably in the Middle East, and most particularly, in Yemen, is the driving force.

Trump’s Love Affair with Oil

Donald Trump, a mere real estate developer before becoming president, has not been shy about his love of the powerful oil industry, whether domestic or Middle Eastern. Defying Washington’s tradition of hiding the role of oil in foreign policy, he has embraced oil power exuberantly and unapologetically, as when he appointed Rex Tillerson, former CEO of Exxon-Mobil, as his first secretary of state shortly after taking office. Then last fall he scandalized the international community when he redeployed American troops to Eastern Syria to “secure our [sic] oil.” Most recently, his administration secretively doled out at least $113 million to oil companies in taxpayer-backed loans under the Paycheck Protection Program, intended for small businesses hurt by Covid-19.

Now Trump’s brazenness is backfiring against his most recent Secretary of State. Members of the House Foreign Affairs Committee and Senate Foreign Relations Committee investigating Linick’s firing last month want to know if it was an act of retaliation by Pompeo. The secretary has denied the charge, but his timing was certainly suspect.

As first reported by the Washington Post on May 16, Linick was wrapping up an investigation of Pompeo’s approval one year ago of unauthorized arms sales worth $8 billion to Saudi Arabia, defying the will of Congress. The weapons’ ultimate destination: the Saudis’ widely condemned war in Yemen, deemed the world’s greatest humanitarian crisis.

Yemen

Linick briefed the State Department of his findings before issuing his report, which assuredly set off alarm bells in Pompeo’s office and plausibly resulted in Linick’s abrupt dismissal. The congressman who originally asked for the investigation, Representative Eliot Engel, Chair of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, told the Washington Post, “We don’t have the full picture yet but it’s troubling that Secretary Pompeo wanted Mr. Linick pushed out before this work could be completed.” In his testimony Wednesday, Linick said a top department official “bullied” him, pressuring him not to pursue his investigation into arms sales to Saudi Arabia. Democratic lawmakers, in a statement released after the testimony, urged the administration “to immediately comply with outstanding requests for additional witness interviews and documents.”

As with all things Middle East, it’s never easy to get the full picture right away. With oil riches gumming up so many human interactions, including war and pretexts for war, assassinations and regime changes, the path to the truth can be littered with lies. It took me decades of research and years of filtering that research into a book, for instance, to figure out what the Great Game for Oil had to do with the death of my father in a mysterious plane crash following his top-secret mission to Saudi Arabia.

Now, at least, I know where to look and how to look when questions loom.

I analogize this to peeling an onion, beginning with the most obvious question.

First peel: Why did Democrats and Republicans object to arms sales to Saudi Arabia last year?

The answer, in this case, can be boiled down to three words: cold blooded murder. The murder victim in this case was a Washington Post columnist and an exiled Saudi national named Jamal Khashoggi. Two months before his death in October, 2018, Khashoggi had written disparagingly about the Saudis’ disastrous war against Yemen, then in its third year. The war had become an acute international embarrassment, especially after Saudi coalition forces bombed a school bus on August 9, 2018 killing forty children and thirty-two nearby civilians. By August 19, CNN reported that the bomb used in the attack was a US-made, 227-kilogram laser guided bomb manufactured by Lockheed Martin.

News like this was not helpful to Saudi Arabia’s reigning crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman (nicknamed MSM), nor to his closest allies, Donald Trump and son-in-law Jared Kushner, who strived to turn Saudi Arabia into a mecca for international investment (think hotels and resorts along the Red Sea). Those ambitions crystallized a few months after the newly elected Trump took then Secretary of State Rex Tillerson on his first official trip overseas in March, 2017 — not (as is tradition) to visit any of our democratic allies, but to visit Saudi Arabia, one of the most oppressive regimes in the world. That trip was made memorable by images of Trump jubilantly dancing the sword dance with his white-robed royal hosts.

As I pointed out in The Crash of Flight 3804, they were dancing for joy after negotiating $350 billion in US aid, including the sale of $100 billion in US armaments to the kingdom. It was a nice quid pro quo: You have oil, we have arms. We can make a lot of money from US arms sales and hotel tourism. provided you modernize Saudi Arabia and institute some reforms like letting women drive. In return, we will help you win your unpopular war in Yemen.

But Jamal Khashoggi kept getting in the way with his Washington Postcolumns. ”Saudi Arabia must face the damage from the past three plus years of war in Yemen,” he wrote on September, 2018. “The conflict has soured the kingdom’s relations with the international community and harmed its reputation in the Islamic world.” But Khashoggi didn’t stop there. He singled out Donald Trump’s “good friend,” crown prince Mohammed bin Salman, for additional criticism: “The crown prince must bring an end to the violence,” he wrote, concluding with a fatal barb, “and restore the dignity of the birthplace of Islam.”

One month later, Khashoggi was brutally murdered, hacked to pieces in the Saudi embassy in Turkey by a bone saw wielded by the head of Saudi security forces. During the ensuing investigation President Trump kept prevaricating over holding MBS (now widely referred to as Mohammed Bone Saw) responsible for Khashoggi’s murder despite international cries for accountability and the CIA’s assessment that MBS was behind the killing. Trump repeatedly reminded Americans of the kingdom’s importance as a “strong ally,” especially as a counterweight to Iranian ambitions in the Middle East. Pompeo, pictured here with the Saudi king just days after the Khashoggi murder, agreed.

Trump simply attributed the murder to “rogue killers” while making no commitment to lessening arms sales to Saudi Arabia. The armaments industry was, after all, creating a lot of jobs, he argued. It didn’t matter that the death toll in Yemen was fast approaching 100,000 since the war began in 2015.

This was just too much for Congress. Democrats and Republicans alike insisted Saudi Arabia would have to be punished for the war in Yemen and the murder of its most ardent critic, who, after all, had written for the powerful Washington Post. In early April, 2019 both the House and the Senate passed the Yemen War Powers Act, a bipartisan bill aimed at stopping all US involvement — including arms sales — to Yemen. On April 19, President Trump vetoed the bill.

The following month he and Pompeo declared emergency powers in order to bypass Congress and deliver $8 billion worth of arms sales, mostly to Saudi Arabia and its wartime ally, the United Arab Emirates, in order to stop “the malign influence of Iran in the middle East.” Once again, members of Congress cried foul, questioning Trump’s legal justification for invoking emergency powers and reiterating their concerns about Saudi Arabia’s dismal human rights record and the murder of Jamal Khashoggi.

Apparently, Representative Eliot Engel never got over Trump’s act of impunity, and so he called upon the Inspector General to investigate.

Second peel: Is there an oil connection to the US-Saudi war in Yemen?

It stands to reason, since Saudi Arabia ignored widespread condemnation to pursue its war in Yemen at all costs. That term, “at all costs,” has been employed repeatedly through decades of endless wars in the Middle East, beginning when my father wrote in a memo to his superiors at the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in 1944 that the oil of Saudi Arabia was so vitally important to US interests that it had to be protected “at all costs.” Protected, that is, by vast amounts of US military assistance to the Kingdom, which from 1950 to the present amounts to trillions of dollars.

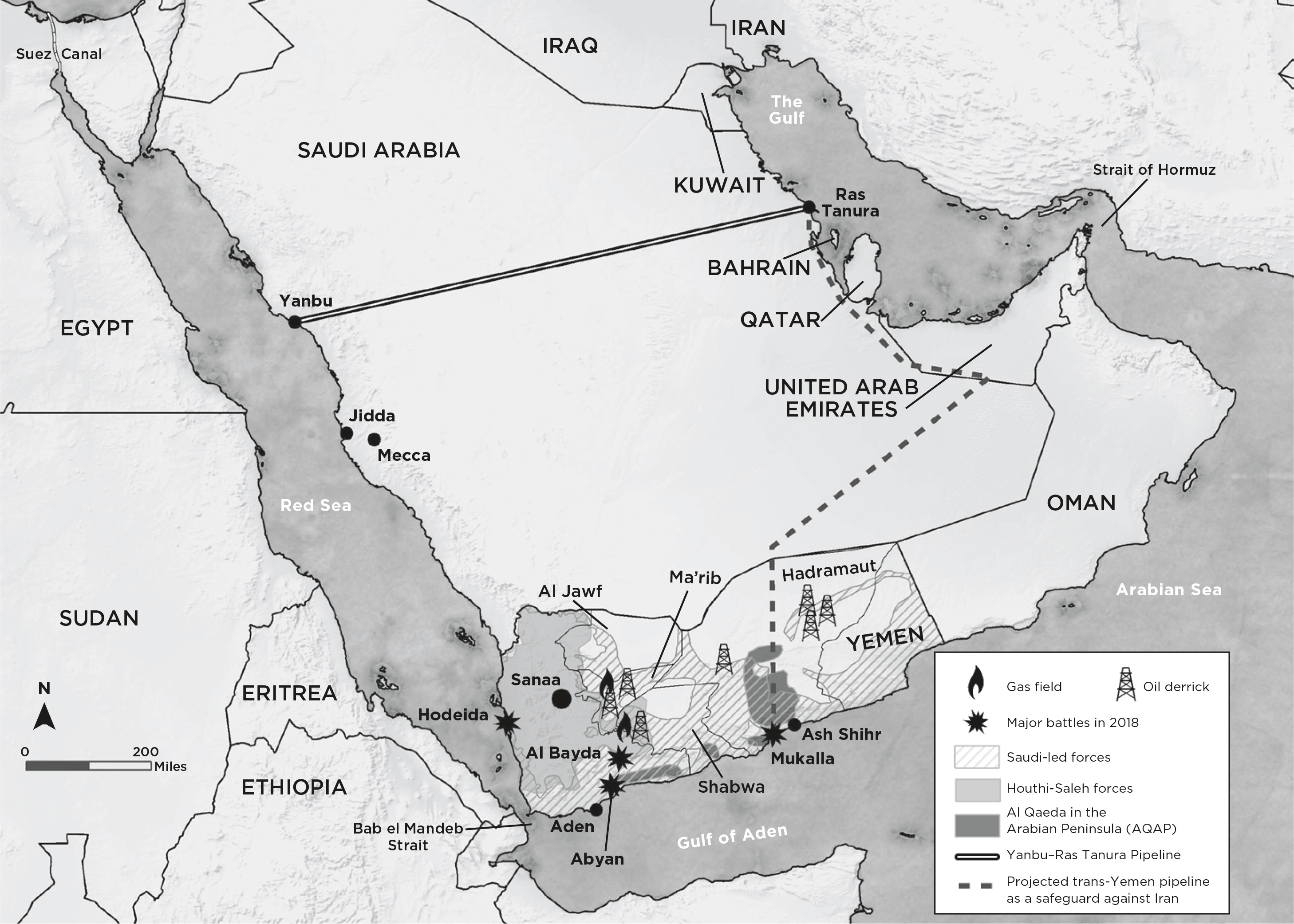

Fact is, Yemen is swimming in oil. Equally significant, the crown prince’s main concern has been “freedom of navigation” for oil tankers carrying Saudi oil, whether they pass through the Strait of Hormuz, a narrow chokepoint at the bottom of the Persian/Arabian Gulf that separates eastern Saudi Arabia from Iran, or the Bab el Mandeb Strait on the western side of the Saudi peninsula. Problems arose in 2015, when Shiite-backed Houthi rebels gained control over much of northern Yemen, pushed out its corrupt pro-Western leader, and took control of Yemen’s capital. Next they began advancing on the oil-producing province of Ma’rib and beyond, toward the Bab el Mandeb Strait. To alleviate these worries, Saudi Arabia has embarked on building a pipeline–despite local protests — that will carry its oil straight to the southern Yemen port of Mukalla, on the Gulf of Aden, avoiding the two chokepoints.

The war in Yemen and the projected Saudi pipeline through Yemen, pictured in “The Crash of Flight 3804″

At the same time, MSM made multiple trips to Washington seeking military aid, part of which would go toward protecting the pipeline.

Third peel: Did alleged threats from Iran warrant Trump’s declaration of emergency?

A series of attacks on oil tankers did, in fact, occur during the spring of 2019 that brought the world perilously close to another Middle Eastern war. The thing is, the identity of the perpetrators remains unresolved. Four oil tankers were damaged in early May, 2019, causing Pompeo to blame Iran, although “without citing specific evidence,” according to the Wall Street Journal. The Iranians vigorously denied the charges, and accused the US of trying to pull Iran into a war. Leaders around the world cautioned against war, including US allies. Pompeo accused Iran again of attacking two oil tankers in the Gulf of Oman in June, again providing no evidence.

Small wonder, with skepticism about Iran’s involvement mounting at home and abroad, that Pompeo’s claim of a national emergency, caused some members of Congress to see the emergency as “phony.”

On September 14, 2019 another international crisis erupted when a series of drone and missile attacks hit Saudi oil facilities in Riyadh, causing significant damage and prompting a warning from President Trump that the US was “locked and loaded” in its readiness to respond. Pompeo declared the attacks an “act of war,” and tried to pull together a coalition at the UN to “deter” Iran. Once again, Iran denied responsibility, this time before the UN General Assembly, and challenged the US to provide evidence. Saner heads prevailed and war was narrowly averted.

But the attack on Saudi Arabia had one salutary effect: a surge in crude oil prices. Who benefited? One group in particular: US shale oil producers, who early on in Trump’s reign became overnight billionaires through heavy borrowing and financial mismanagement. Noted Bloomberg.com, “American shale producers, one of the worst-performing segments on the stock market this year, jumped Monday morning after an attack on a Saudi Arabia oil production facility over the weekend sent crude prices soaring.The spike in oil prices offers relief at a critical time for U.S. shale producers, which have seen investors flee after the sector largely failed to generate shareholder returns while rapidly growing output.”

Could this mean President Trump created a phony emergency and risked war with Iran to help his embattled friends (described in my previous blog) in the shale oil industry? So far, Pompeo has yet to turn over witnesses and documents. But if the truth ever comes out, it will surely confirm that protecting the riches of oil, “at all costs,” will trump protecting the rights of ordinary individuals here and abroad.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

This article was originally published on Medium.

Charlotte Dennett is an author, investigative journalist, and attorney. Recently published The Crash of Flight 3804 about the death of her master-spy father in the Great Game for Oil.

All images in this article are from Medium unless otherwise stated