“Salt of the Earth”: A Successful Combination of Inspiration and Perspiration

Review of the movie Salt of the Earth (1954)

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

***

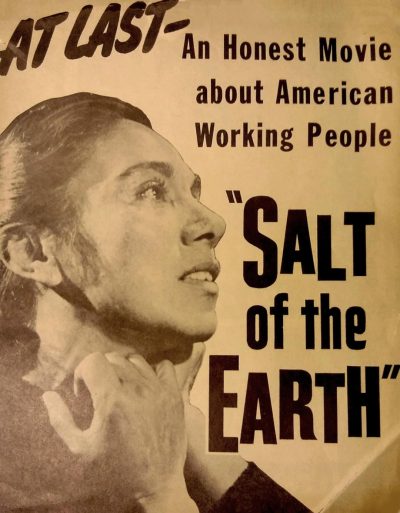

Poster promoting the theatrical premiere of the 1954 American film Salt of the Earth at a (now demolished) theater on 86th Street in Manhattan. Mexican actress Rosaura Revueltas, who played the leading role, is shown.

Born in controversy but then ignored in its youth, the film Salt of the Earth has matured beautifully into a classic film in the neorealist style. Set in Zinc Town, New Mexico, a mining community with a majority of Mexican-Americans strike for working conditions equal to those of the white, or “Anglo” miners. The town and the mine is run by Delaware Zinc Inc. who refuse to negotiate with the workers and the strike goes on for months. The story focuses on Ramon Quintero (Juan Chacón) and his wife Esperanza Quintero (Rosaura Revueltas) who is pregnant with their third child. Ramon is arrested by police and beaten in prison at the same time his wife gives birth to their new baby.

When Ramon is released he counters resistance to his activities by Esperanza and he points out their struggle is for their children’s futures too. The company then uses the Taft-Hartley Act injunction on the union forbidding picketing. However, the wives realise there was nothing to stop them from taking the men’s places on the picket line. A lot of the men are quite traditional and are not happy seeing their wives on what can be a dangerous and violent place on picket lines. Ramon forbids Esperanza to go but eventually relents. However, as the full film is freely available online for you to watch on the Salt of the Earth wikipedia.org page, I will not go into full details here.

The involvement of the women is one of the most interesting aspects of the film as they rather timidly, at first, assert that their issues regarding hygiene (sanitation and ‘decent plumbing’) are as important as the safety of the men, and Esperanza is annoyed that ‘what the wives want always comes later’. Over time the women gain more experience dealing with the police and scabs, and consequently gain more confidence in their demands too. As the mine had already been unionised the film’s real narrative dwells more on showing the men how the union is strengthened by the involvement of the whole community.

Union Meeting

The production of Salt of the Earth faced many difficulties from locations, cameramen to actors. A small plane buzzed overhead and anti-communists fired at the sets. They eventually found a documentary cameraman who was willing to take the risks involved with working on the project. Later, Rosaura Revueltas (Esperanza Quintero) the lead actor, was deported to Mexico and the editors had to cut in previously filmed footage to finish the narrative.

The origin of the film’s woes stretched back some years when the director Herbert Biberman refused to answer the House Committee on Un-American Activities in 1947 on questions of affiliation to the Communist Party USA, and he became known as one of the Hollywood Ten who were cited and convicted for contempt of Congress and jailed. This meant that Biberman (as well as actors, screenwriters, directors, and musicians) were denied employment in the entertainment industry for years after. During the making of Salt of the Earth Biberman was hounded by Roy Brewer. Roy Martin Brewer (1909–2006) was an American trade union leader who was prominently involved in anti-communist activities in the 1940s and 1950s. He accompanied Ronald Reagan on his first visit to the Whitehouse.

Brewer tried many times to stop the production of Salt of the Earth. He believed that “officers of the Writers’ Guild were under the domination of the Communist Party until the hearings of 1947. During that time they began to change the mind, the creative minds, of the people who made these pictures and they didn’t do it by selling them communism. They got them to accept the idea that it was the obligation of a writer to put a message in the film.”

Paul Jarrico (1915–1997) the blacklisted American screenwriter and film producer of Salt of the Earth commented on Brewers statements:

“The studio reluctance to make message movies started long before the blacklist and Brewer’s attribute to our cleverness in manipulating the culture of America is undeserved. We were unable to get anything more than the most moderate kind of reform messages into our films and if we thought we got some women treated as human beings rather than as sex objects we thought it was a big victory and in fact one of the reasons we made Salt of the Earth after we were blacklisted was to commit a crime worthy of the punishment having already been punished for subverting American films, it was all ridiculous.”

Members of the Hollywood Ten and their families in 1950, protesting the impending incarceration of the ten

To make matters worse, Salt of the Earth had been sponsored by a Union (the International Union of Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers) and many blacklisted Hollywood professionals helped produce it. After editing in secret, the release of the film was met with an American Legion call for a nationwide boycott and the majority of theaters refused to show it. For ten years the film was ignored in the USA while finding an audience and accolades in Eastern and Western Europe. In the 1960s the film was seen by larger audiences in union halls, women’s associations, and film schools.

The narrative of the film was based on an actual strike which had occurred only a couple of years before the production of Salt of the Earth:

“The film recreates the 1951-2 strike against the Empire Zinc Company in New Mexico where a court injunction barred workers of the Local 890 chapter of the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Works from the picket line. As the strike continued, the community’s women assumed increasingly active leadership roles in the protests, defiantly picketing Empire Zinc themselves. The 15-month strike ultimately led to considerable gains for the workers and their families.”

The film not only laudably covered labour rights and women’s rights but also minority rights. As Mercedes Mack writes:

“On October 17, 1950, in Hanover, New Mexico, workers at the Empire Zinc mine finished their shifts, formed a picket line, and began a fifteen-month strike after attempts at union negotiation with the company reached an impasse. Miner demands included: equal pay to their White counterparts, paid holidays and equal housing. As a larger objective, the Local 890 Chapter of the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers was to end the racial discrimination they suffered as a product of the institutions created by the Empire Zinc company in their town. For example, Mexican-American workers were subject to separate pay lines, unequal access to sanitation, electricity and paved streets as a result of discrimination by company sponsored housing, segregated movie theaters, etc. […] While women continued the strike, men assumed household duties and were not the center of the movement anymore. In January 1952, the strikers returned to work with a new contract improving wages and benefits. Several weeks later, Empire Zinc also installed hot water plumbing in Mexican American workers’ houses–a major issue pushed by the women of these households.”

The producers and director used actual miners and their families as actors in the film in neorealist style. Christopher Capozzola describes how:

“Paul and Sylvia Jarrico heard of the strike and went to Grant County to walk the picket line; within a year, Michael Wilson was in town. Although Wilson started the script, the men and women of Local 890 finished it, insisting in the era of Ricky Ricardo that Latino/a characters would be favorably presented in the mass media. Biberman cast only five professional actors, among them a young Will Geer (better known to television viewers as the folksy Grandpa Walton) and the leftist Mexican actress Rosaria Revueltas, who called Salt of the Earth “the film I wanted to do my whole life.” Strike participants filled the ranks, most memorably Juan Chacón, who played the leading role of Ramón Quintero. His emotional richness and sly humor make him far and away the film’s best performer.”

In 1982, a documentary about the making of Salt of the Earth was released, titled A Crime to Fit the Punishment and was directed by Barbara Moss and Stephen Mack. The full documentary can be seen online here.

The making of Salt of the Earth was also the subject of a Spanish-British bio-picture in 2000. The film, titled One of the Hollywood Ten, was written and directed by Karl Francis and stars Jeff Goldblum and Greta Scacchi.

Salt of the Earth still stands up there as one of the great union films along with Blue Collar (1978) and Norma Rae (1979). However, its authenticity and sincerity arising from working directly with workers, and its successful production despite so many obstacles put in its way, will make it one of the most inspiring union films ever produced.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin is an Irish artist, lecturer and writer. His artwork consists of paintings based on contemporary geopolitical themes as well as Irish history and cityscapes of Dublin. His blog of critical writing based on cinema, art and politics along with research on a database of Realist and Social Realist art from around the world can be viewed country by country here.

He is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization.

All images in this article are from the author unless otherwise stated