Russia’s Strategic Waterways and the Northeast Arctic Passage

Russia would have obviously preferred that the Kerch Strait Crisis with Ukraine never happened, but since it did, Moscow’s wasting no time in taking advantage of the highly publicized defense of its maritime borders in the Black Sea to promote a similar policy towards its sovereign waters in the Arctic Ocean, though the US might contest some of Russia’s claims there in the future under the pretext of promoting the so-called “freedom of navigation” principle.

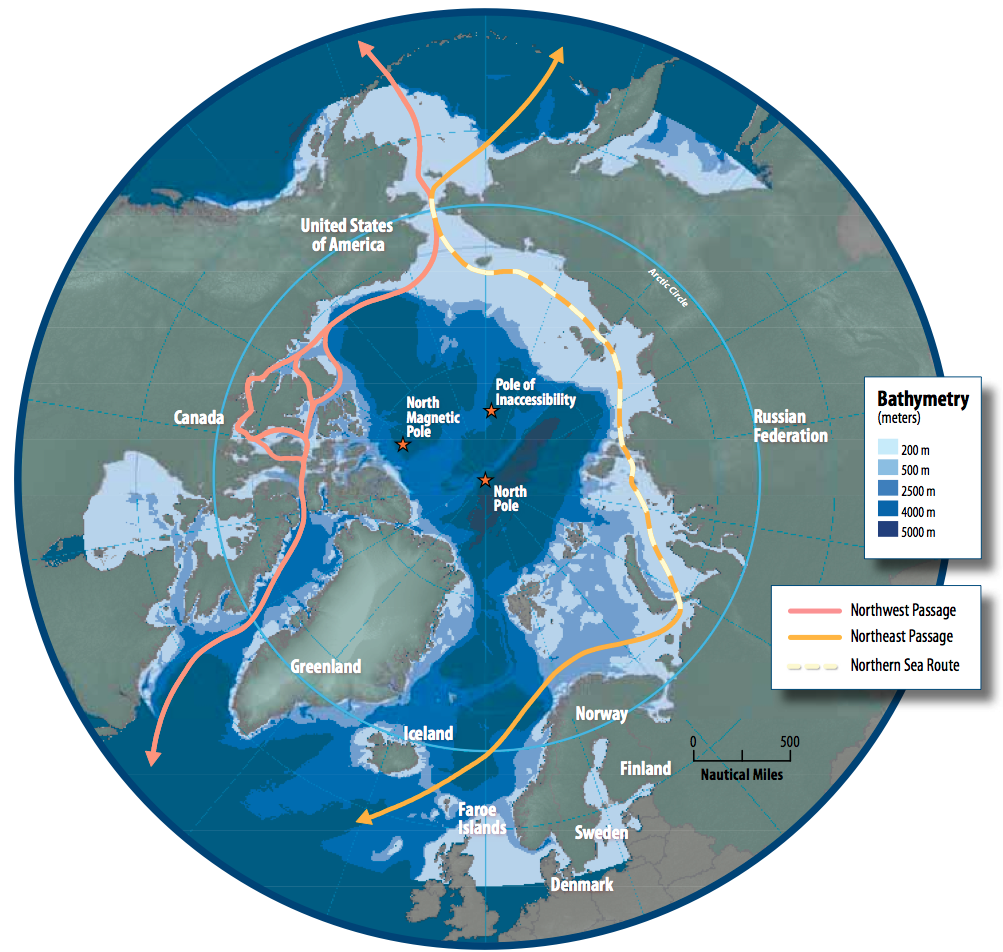

Sputnik reported on Friday that Russia will implement a policy from 2019 onwards requiring all foreign military vessels to seek its approval before transiting through its territorial waters when utilizing the Northern Sea Route between Western and Eastern Eurasia. This is a sensible strategy for safeguarding the country’s sovereignty, especially in the immediate aftermath of the Kerch Strait Crisis with Ukraine, which can be seen in hindsight as having spurred the Kremlin to make this announcement. In fact, while Russia would have obviously preferred for the Black Sea incident to have never happened, it’s wasting no time in using it as the reason for rolling out a more robust policy for unambiguously defending its maritime interests in the Arctic Ocean, which are set to become more important than ever in the coming years as the gradual melting of sea ice there opens up access to what has historically been called the Northeast Passage.

Looking at the map, it may not seem like that big of a deal for Russia to declare that foreign military vessels can’t transit through its territorial waters without receiving prior approval since the shortest geographic route from the American-shared Bering Strait to the European gateway of the Norwegian Sea goes directly through the North Pole, but it must be remembered that this part of the Arctic Ocean will probably still remain frozen for years to come.

source: Wikipedia

This means that all vessels traversing this route will more than likely have to pass through Russia’s internationally recognized maritime territory at some point or another in order to continue their voyage across the northern reaches of the Eastern Hemisphere, hence the applicability of the promulgated policy in having Moscow act as the geopolitical gatekeeper of this connectivity corridor. It’s within Russia’s sovereign right to do so, and after the Kerch Crisis, there aren’t any questions about its commitment to defending its territorial interests.

Accepting this, the US and its allies are highly unlikely to attempt to test Russia’s fortitude in this respect, although the scenario of course can’t ever be precluded. Nevertheless, it’s much more likely that Russia will grant the privilege of military passage to warships from its Chinese and Indian partners, seeking to strike a “balance” between both of them as it facilitates their use of the Northern Sea Route, especially in the event that they’re traversing it en route to ports of call in Europe. Even if they aren’t, each of them are investing in different energy extraction projects in the region, so it might serve domestic political purposes in both Great Powers to occasionally dispatch their ships on friendly visits to their Russian partner’s Arctic ports. While the US would probably welcome India’s presence there, its allied Mainstream Media outlets across the world will probably fearmonger about China’s.

Moving out of the infowar realm and into the sphere of tangible geopolitics, however, the US might actually be cooking up a scheme to challenge Russia’s Arctic claims, albeit those which aren’t yet internationally recognized by the UN. It shouldn’t be forgotten that Russia claims a broad swath of the Arctic Ocean by virtue of the Siberian-originating underwater Lomonosov Ridge that extends all the way up to the North Pole, which Moscow believes makes the surrounding waters its sovereign territory per the clauses contained in the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). It’s already submitted an application to the global body to hear its case and eventually rule on whether to recognize it, which could then possibly put this massive stretch of the sea under Russia’s military protection per its recently promulgated policy of requiring advance notification from foreign warships before they traverse through its territory.

As Arctic ice melts ever more with the passing of time, it’ll inevitably get to the point where the waters beyond Russia’s present maritime territory there become navigable during at least some months of the year, thereby opening up the theoretical possibility of foreign warships sailing through them. Thus, it’s important for Russia to assert control over as much of this waterway as possible in order to prevent hostile forces from encroaching too close to its coast, to say nothing of the economic incentive that it and its competitors have to mine this resource-rich region and correspondingly protect their investments there. The problem, however, is that the US isn’t a party to UNCLOS, and while de-facto recognizing most of its authority, still “officially” doesn’t abide by this framework and believes that it has the “exceptional” right to sail its warships wherever it pleases, hence one of the publicly stated reasons why it’s provoking China in the South China Sea.

It therefore wouldn’t be a stretch of the imagination to predict that the US might one day militarily challenge Russia’s UNCLOS claim to large parts of the Arctic Ocean, doing so on the basis that it doesn’t regard those waters as being under Moscow’s control and wanting to promote the so-called “freedom of navigation” principle there as its “plausible” pretext for “justifying” this provocative move. The reader should keep in mind that this scenario is still years away from possibly transpiring because those maritime areas are still largely frozen and will probably remain so for a while to come, meaning that it wouldn’t be realistic for the US to even seriously contemplate this until then. Nevertheless, if there’s any “silver lining” to emerge from the Kerch Crisis, it’s that Russia proved that it will resolutely defend its sovereign maritime interests, so explicitly expanding this policy to the Arctic Ocean might give the US cause to consider whether it’s worth poking the Russian Bear there.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

This article was originally published on Eurasia Future.

Andrew Korybko is an American Moscow-based political analyst specializing in the relationship between the US strategy in Afro-Eurasia, China’s One Belt One Road global vision of New Silk Road connectivity, and Hybrid Warfare. He is a frequent contributor to Global Research.

Featured image is from teleSUR