Russia’s “Fourteen Points” for a European Security Policy: Why Was Moscow’s 2009 Proposal Rejected?

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name (only available in desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Click the share button above to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Global Research Referral Drive: Our Readers Are Our Lifeline

Important article by Vladislav Sotirovic first published on April 26, 2024

***

In 2009, Russian President Medvedev (President from May 7th, 2008 to May 7th, 2012) called for a new European security policy known as “Fourteen Points” as a new security treaty to be accepted to maintain European security as the ability of states and societies to maintain their independent identity and functional integrity (this Russian draft European security treaty was originally posted on the President’s website on November 29th, 2009).

This treaty proposal was passed to the leaders of the Euro-Atlantic States and the executive heads of the relevant international organizations such as NATO, EU, the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), and the Organization of Security Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). In this proposal, Russia stressed that it is open to any democratic proposal concerning continental security and is counting on a positive response from Russia’s (Western) partners.

However, not so surprisingly, D. Medvedev’s call for a new European security framework (based on mutual respect and equal rights) became interpreted particularly in the USA in the fashion of the Cold War 1.0, in fact, as a plot to pry Europe from its strategic partner (USA).

Nevertheless, this program in the form of a proposal was the most significant initiative in IR by Russia since the dismissal of the USSR in 1991. From the present perspective, this proposal could save Ukrainian territorial integrity but it was rejected primarily due to Washington’s Russophobic attitude.

As a matter of fact, Moscow since 1991, and particularly since 2000, viewed NATO as a Cold War 1.0 remnant and the EU as no more but only as a common economic-financial market with many crisis management practices. Nevertheless, Medvedev’s 2009 “Fourteen Points” was announced on November 29th, 2009 Russia published a draft of a European Security Treaty. Medvedev’s program resembles the program drawn up by US President Woodrow Wilson (issued on January 8th, 1918), who had emancipated peace aims in his well-known “Fourteen Points”. These two programs have two things in common:

1) Both documents advocate multilateralism in the security area and devotion to international law; and

2) They are very idealistic in terms of the tools needed for their implementation.

The Russian proposal from 2009 is founded on existing norms of international security law according to the UN Charter, Declaration on Principles of International Law (1970), and the Helsinki Final Act of the Conference for Security and Cooperation in Europe (1975) followed by the Manila Declaration on the Peaceful Settlement of International Disputes (1982) and the Charter for European Security (1999).

The 2009 Russian proposal on European Security (ten years after the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia) can be summarized in the following six points:

- Parties should cooperate on the foundation of the principles of indivisible, equal, and unrelieved security;

- A Party to the Treaty shall not undertake, participate in, or support any actions or activities significantly detrimental to the security of any other party or parties to the treaty;

- A Party to the treaty which is a member of military alliances, coalitions, or organizations shall work to ensure that such alliances, coalitions, or organizations observe principles of the UN Charter, the Declaration of Principles of International Law, the Helsinki Final Act, the Charter for European Security followed by certain documents adopted by the OSCE;

- A Party to the treaty shall not allow the use of its territory and shall not use the territory of any other party to prepare or carry out an armed attack against any other party or parties to the treaty or any other actions affecting significantly the security of any other party or parties to the treaty;

- A clear mechanism is established to address issues related to the substance of this treaty and to settle differences or disputes that might arise between the parties in connection with its interpretation or application;

- The treaty will be open for signature by all states of Euro-Atlantic and Eurasian space followed by several international organizations: the EU, the OSCE, the CSTO; NATO, and the CIS.

Russia, in fact, understood the treaty as a reaffirmation of the principles guiding security relations between states but above all respect for independence, territorial integrity, sovereignty within nation-state borders, and the policy not to use force or the threat of its use in IR.

Actually, the security issue in Europe became a strategic agenda for Russia from 2000 onward. During its whole post-Soviet history, Russia felt very uncomfortable as put on the margins of the process of the creation of a new (US/NATO-run) security order in Europe based on the NATO enlargement toward the borders of Russia.

It has to be remembered that Moscow at that time proposed to Washington and Brussels three conditions that, if accepted by NATO, might make enlargement acceptable to Russia:

- A prohibition against stationing nuclear weaponry on the territory of new NATO members;

- A requirement for joint decision-making between NATO and Russia on any issue of European security especially where the use of military force was involved; and

- Codification of these and other restrictions on NATO and rights of Russia in a legally binding treaty.

However, none of these proposed conditions of NATO-Russia security cooperation in Europe was accepted.

After this failure, a new military doctrine of the Russian Federation from 2010 accepted the reality that the existing international security architecture including its legal mechanism does not provide equal security for all states (a phenomenon of the so-called “asymmetric security”). The same doctrine clearly stressed that NATO’s ambitions to become a supreme global actor and to expand its military presence toward Russia’s borders became a focal external military threat for Russia. Surely, from 2010, it became clear to Moscow that NATO has not accepted the Russian proposal to create a common European security framework functioning on the principle of “symmetric” relations including certain duties and rights equal for both sides.

Nevertheless, the time when Moscow suggested a new security initiative was very appropriate for the matter of the declination of both soft and hard power of the Collective West (USA/EU/NATO) as a result of the second war against Iraq and the global economic meltdown. Since the disasters of Iraq, Guantánamo, and Abu Ghraib, Washington and its Western allies lost any moral credibility and authority to claim global leadership. In addition, Western support for Georgian aggression and the corrupted regime of Mikheil Saakashvili revealed once more the Atlanticist disregard for real democracy and justice. Simultaneously, the global economic and financial crisis spelled the end of the neoliberal fiction of globalization confirming at the same time Western unsuccess in regulating global finance. Consequently, the unipolar IR around the Collective West ceased to shape and direct both global geopolitics and geoeconomics.

The Russian (in fact, President Dmitry Medvedev’s) proposal for a new security agreement with NATO was a serious test of the honesty of the Collective West versus Russia.

Simply, the proposal called for a new treaty to implement already accepted previous declarations since the end of the Cold War 1.0 that the West and Russia are friends, security is indivisible, and nobody’s security can be enhanced at the cost of others.

Basically, the new security treaty should be founded on a multilateral system, rather than a system based on hegemony or bipolarity.

Behind the proposal was the rejection of a hegemonic role for the USA.

However, the crucial question was:

Does the USA want to participate in multilateral efforts to address issues of both European and global security challenges?

Nonetheless, very soon it became clear that this Russian agenda for a new European security concept was seen by Western policymakers as an attempt to undermine NATO and its eastward expansionistic policy.

In other words, President D. Medvedev’s proposal for the new security design in Europe was understood by the Westerners as a perfidy intention to change the terms of the debate on the future of the European security system without the participation from NATO to the direction of the new body that includes Russia as a founding member and, therefore, as a pillar of a new security framework of the Old Continent. Therefore, his proposal, as such, was unacceptable to the Collective West.

It has to be stressed that the most difficult step in the rapprochement between Russian and Western competing European security agendas after the Cold War 1.0 was and still is the politicized attitude by the pro-Western part of Europe (EU/NATO) that Russia is posing security danger to the continent. However, on the opposite side, Russia’s security fears come primarily at least from the policy of NATO’s eastward enlargement if not from the question of NATO’s existence after 1991 in general.

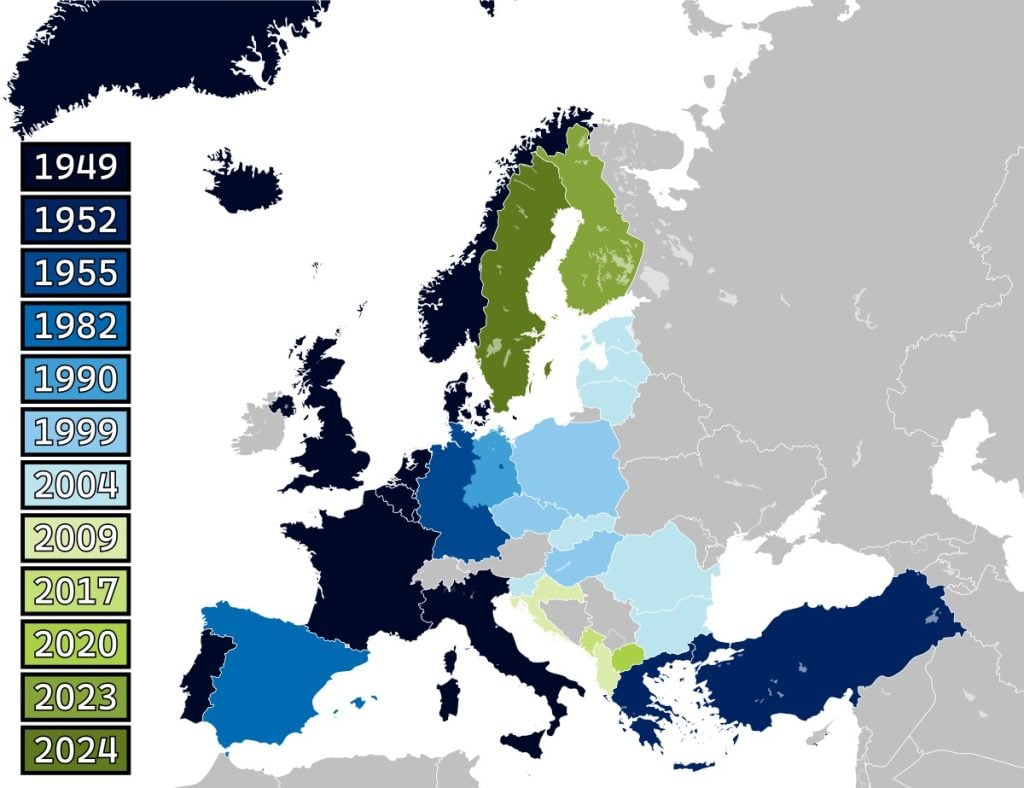

NATO enlargement

After all, it appears that, in fact, the focal problem was not about keeping the status quo in terms of the European security framework, but, however, what a new security system was going to be. In other words:

- Should it be a NATO-centric structure (as it has been since 1991)? In this case, NATO will be turned into a forum for consultation on both European and global security questions; or

- Should it be a new institutional framework founded on a legally framed treaty that guarantees equality and indivisibility of security of all political subjects (states)?

The Russian 2009 “Fourteen Point” security program represented at that time, actually, the first positive foreign policy initiative by Moscow since the dissolution of the Soviet Union. This D. Medvedev’s initiative had both real geopolitical meaning and many diplomatic symbolic features. The initiative’s crucial value was that:

- It advocated the formation of a new European security framework founded on new and democratic principles of the indivisibility of international security and the inclusiveness of all interested and relevant actors; and

- The focal objectives of the initiative were to upgrade the already existing (but ineffective) European security system and to expand it into the region of Asia-Pacific for the sake of creating a common security area from Alaska to Siberia.

It was, however, obvious that the creation of such a security system would preserve primarily Russian national interests in both regions primarily in Europe but in Asia-Pacific as well. In addition, the proposal will pave the way for integrating a rising China and other countries of Asia into a complex network of the European security framework. Nonetheless, the proposal was rejected in the name of further NATO eastward expansion which was in many Western eyes the most fateful error of the US policy during the whole period of the post-Cold War 1.0 era.

Such NATO policy, in fact, inflamed nationalistic, anti-Western, and militaristic feelings in Russia, and finally restored the policy of Cold War 1.0 into Cold War 2.0 (a renewed East-West security competition in Europe) keeping in mind the fact that in Russia, exists strong belief, based on accounts by Mikhail Gorbachev, Evgenii Primakov, and other Russian most influential policymakers, that Washington has broken its commitment not to expand NATO as a precondition for German reunification in 1989−1990.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share button above. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Dr. Vladislav B. Sotirović is a former university professor in Vilnius, Lithuania. He is a Research Fellow at the Center for Geostrategic Studies. He is a regular contributor to Global Research.