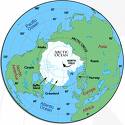

Russia and America Clash in the Arctic? Arctic Region. Prime Target of U.S. Expansionist Strategy

-The US and Canada have agreed to put aside their dispute over navigation rights off the Canadian coast to stand up jointly to Russia. Last year Nato, for the first time, officially claimed a role in the Arctic, when Secretary-General Jaap de Hoop Scheffer told member-states to sort out their differences within the alliance so that it could move on to set up “military activity in the region.” “Clearly, the High North is a region that is of strategic interest to the Alliance,” he said at a Nato seminar in Reykjavik, Iceland, in January 2009.

Since then, Nato has held several major war games focussing on the Arctic region. In March this year, 14,000 Nato troops took part in the “Cold Response 2010” military exercise held in Norway under a patently provocative legend: the alliance came to the defence of a fictitious small democratic state, Midland, whose oilfield is claimed by a big undemocratic state, Nordland. In August, Canada hosted its largest yet drill in the Arctic, Operation Nanook 2010, in which the US and Denmark took part for the first time.

Russia and the United States have made headway in improving their relations on arms control, Afghanistan and Iran but there is one area where their “reset” may yet run aground — the Arctic. The US military top brass warned of a new Cold War in the Arctic and called for stepping up American military presence in the energy-rich region.

Earlier this month, US Admiral James G Stavridis, supreme Nato commander for Europe, said global warming and a race for resources could lead to a conflict in the Arctic because “it has the potential to alter the geopolitical balance in the Arctic heretofore frozen in time.”

Echoing similar views, Coast Guard Rear Admiral Christopher C. Colvin, who is in charge of Alaska’s coastline, said Russian shipping activity in the Arctic Ocean was of particular concern for the US. He called for more military facilities in the region.

The statements are in line with the US policy. It calls for “deployment of sea and air systems for strategic sealift, strategic deterrence, maritime presence, and maritime security” to “preserve the global mobility of the US military and civilian vessels and aircraft throughout the Arctic region” including the North Sea Route along Russia’s Arctic coast, which Moscow regards as its national waterway. Russia is the prime target of the US expansionist strategy.

Two months ago, the first Russian supertanker sailed from Europe to Asia along the North Sea route. Next year, Russia plans to send more ships across the Arctic route, 9,000 km off the traditional route via the Suez Canal.

The US Geological Service believes that the Arctic contains up to a quarter of the world’s unexplored deposits of oil and gas. Washington also disputes Moscow’s effort to enlarge its Exclusive Economic Zone in the Arctic Ocean. Under the 1982 United Nations Law of the Sea Convention, a coastal state is entitled to a 200-nautical mile EEZ and can claim a further 150 miles if it proves that the seabed is a continuation of its continental shelf.

Russia was the first to apply for an additional EEZ in 2001 but the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf asked for harder scientific evidence to back the claim. Moscow said it would resubmit its claim in 2013. However, the US has not ratified the UN Convention as many Congressmen fear it would restrict their Navy’s “global mobility.”

Despite the end of the Cold War, the potential for conflict in the Arctic has increased recently the scramble of the five Arctic littoral states — Russia, the US, Canada, Norway and Denmark (through its control of Greenland) – for chalking out claims to the energy-rich Arctic as the receding Polar ice makes its resources more accessible and opens the region to round-the-year shipping. All claims are overlapping and the five states are locked in a multitude of other bilateral disputes. But, at the end of the day, it is Russia against the others, all Nato members.

The US and Canada have agreed to put aside their dispute over navigation rights off the Canadian coast to stand up jointly to Russia. Last year Nato, for the first time, officially claimed a role in the Arctic, when Secretary-General Jaap de Hoop Scheffer told member-states to sort out their differences within the alliance so that it could move on to set up “military activity in the region.” “Clearly, the High North is a region that is of strategic interest to the Alliance,” he said at a Nato seminar in Reykjavik, Iceland, in January 2009.

Since then, Nato has held several major war games focussing on the Arctic region. In March this year, 14,000 Nato troops took part in the “Cold Response 2010” military exercise held in Norway under a patently provocative legend: the alliance came to the defence of a fictitious small democratic state, Midland, whose oilfield is claimed by a big undemocratic state, Nordland. In August, Canada hosted its largest yet drill in the Arctic, Operation Nanook 2010, in which the US and Denmark took part for the first time.

Russia registered its firm opposition to the Nato foray, with President Dmitry Medvedev saying the region would be best without Nato. “Russia is keeping a close eye on this activity,” he said in September. “The Arctic can manage fine without Nato.” The western media portrayed the Nato build-up in the region as a reaction to Russia’s “aggressive” assertiveness, citing the resumption of Arctic Ocean patrols by Russian warships and long-range bombers and the planting of a Russian flag in the North Pole seabed three years ago.

It is conveniently forgotten that the US Navy and Air Force have not stopped Arctic patrolling for a single day since the end of the Cold War. Russia, on the other hand, drastically scaled back its presence in the region after the break-up of the Soviet Union. It cut most of its Northern Fleet warships, dismantled air defences along its Arctic coast and saw its other military infrastructure in the region fall into decay.

The Arctic has enormous strategic value for Russia. Its nuclear submarine fleet is based in the Kola Peninsula. Russia’s land territory beyond the Arctic Circle is almost the size of India — 3.1 million sq km. It accounts for 80 per cent of the country’s natural gas production, 60 per cent of oil, and the bulk of rare and precious metals. By 2030, Russia’s Arctic shelf, which measures 4 million sq km, is expected to yield 30 million tonnes of oil and 130 billion cubic metres of gas. If Russia’s claim for a 350-mile EEZ is granted, it will add another 1.2 million sq km to its possessions.

A strategy paper Medvedev signed in 2008 said the polar region would become Russia’s “main strategic resource base” by 2020. Russia has devised a multivector strategy to achieve this goal. First, it works to restore its military capability in the region to ward off potential threats. Russia is building a new class of nuclear submarines armed with a new long-range missile. Navy Chief Admiral Vladimir Vysotsky said recently he had also drawn up a plan to deploy warships in Russia’s Arctic ports to protect polar sea routes.

A second strategy is to try and resolve bilateral disputes with other Arctic nations. In September, Russia and Norway signed a border pact settling their 40-year feud over 175,000 sq.km in the Barents Sea and agreeing to jointly develop seabed oil and gas in the region.

Even as Russia continues to gather geological proof of its territorial claims in the Arctic, it is ready for compromises. Canadian Foreign Minister Lawrence Cannon did not rule out, after his recent talks in Moscow, that Canada and Russia could submit a joint application to the UN for the Lomonosov Ridge, an underwater mountain stretching from Siberia to Canada, which both countries claim as an extension of their continental shelves.

A third direction of Russia’s policy is to promote broad international co-operation in the region. Addressing Russia’s first international Arctic conference in Moscow in September, Prime Minister Vladimir Putin called for joint efforts to protect the fragile ecosystem, attract foreign investment in the region’s economy and promote clean environment-friendly technologies. He admitted that the interests of the Arctic countries “indeed clash,” but said all disputes could be resolved through international law.