Roots of Aretha Franklin, Proletarian Culture and the Rise of Black Detroit

Queen of Soul was an outstanding manifestation of the African American struggle for dignity and freedom

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above

Detroit artist and social activist Aretha Franklin passed into her ancestral realm on Wednesday morning August 16 while surrounded by family and friends in her Detroit Riverfront condominium downtown.

It had been announced the previous week that Aretha was gravely ill and was hospitalized.

Later press accounts indicated that she was checked out of the hospital and sent home possibly under hospice care. These were difficult reports for many people in the Detroit area to accept at their face value.

The Queen of Soul had been ill in the past and hospitalized. Several years before, media accounts claimed she was suffering from pancreatic cancer and was terminal. However, contradictory claims publicized through television, radio, print and internet platforms said these reports were unsubstantiated.

Several weeks later Aretha was seen attending a Piston’s basketball game at the Palace in Auburn Hills. Although she had lost considerable weight, her appearance and activity illustrated that the Queen was by no means making an immediate exit from the stage.

Just last year in June (2017), Aretha was honored in downtown Detroit through the renaming of a street after her while on the same day performing a free concert for the people of the city. Long term friends of Aretha such as Mary Wilson, formerly of the Supremes, Freda Payne, solo vocalist, the boxing champion Tommy Hearns and the Rev. Jesse Jackson accompanied the Queen of Soul when she entered the concert venue and while leaving.

Her passing has left a tremendous void in the social and cultural atmosphere in the city, nationally and internationally. The loss could be especially felt in Detroit because the landmarks of her upbringing and public celebrity ascendancy are still in existence and constitute key elements of the historical legacy of the African American community.

Origins and Catapulting to World Notoriety

Aretha Franklin was the second daughter and third child of Rev. C.L. Franklin and Barbara Siggers. She was born in Memphis, Tennessee on March 23, 1942 during World War II.

Her father, originally from the Delta region of Sunflower County, Mississippi, began preaching as a teenager in small rural churches. Aretha’s mother, Barbara Siggers, was a musician and vocalist who was born in Shelby, Mississippi. In later years renowned gospel singer Mahalia Jackson said Aretha’s mother had one of the most beautiful voices in the field of sacred music.

Rev. C.L. Franklin was an effective public speaker and vocalist as well. He was brought to Memphis to preach at New Salem Baptist Church where he remained until 1944. For the following two years he served as pastor at Friendship Baptist Church in Buffalo, New York.

In late 1945 Franklin visited Detroit to address the National Baptist Convention where he so impressed members of New Bethel, a church formed 14 years earlier as a women’s prayer group, that they invited him to pastor their congregation in the city. It was during this period of the late 1940s and early 1950s that Aretha’s father would become a nationally known religious figure.

His sermons were broadcast over radio on Sunday evenings directly from New Bethel which was located at the time on Hastings Street and Willis on the eastside. Music store and studio owner Joe Von Battle would be the first person to record and produce Franklin’s sermons and songs on vinyl. The circulation of his records on a mass level along with the broadcast of his sermons over W-LAC radio in Nashville, a station with a powerful range during evening hour, could be picked up in various regions of the United States.

Aretha and Rev. Franklin’s other children were brought up in the church where they participated in the choir. By 1956, Aretha had released her first recordings through the JVB label based on Hastings in the heart of the African American community at the time.

Detroit and the Convergence between National Liberation and Working Class Struggles

Rev. C.L. Franklin had selected the right municipality to launch a successful public career. The city had been a center of migration for African Americans since the early years of the 20th century with the development and expansion of mass production utilizing the assembly line.

This migration accelerated after the beginning of World War I and continued from the 1920s through the period of WWII. The growth of heavy industry and parallel service sectors created a large working class which was divided along racial lines.

It was in 1942-43, the two years after the entry of the U.S. into the War, that racial unrest erupted in the city. Competition over scarce housing resources and public accommodations fueled by the exploitative character of industrial racialized capitalism, resulted in one of the deadliest outbreaks of racial unrest in June 1943. 34 people were killed, 25 of whom were African Americans, in the unrest which lasted for several days where 6,000 federal troops were deployed in an ostensible effort to restore order.

At least 17 of the African Americans killed fell victim to police and Michigan National Guard attacks. Others were murdered by blood thirsty white mobs which accosted African Americans along Woodward Avenue and other areas. African Americans retaliated against whites by destroying white-owned businesses in the heavily-populated Paradise Valley area on the near eastside which was a residential and business district occupied by Black working class people.

The white political establishment including the-then Mayor Edward Jeffries blamed African Americans for the violence. They described African American youth as “hoodlums” hell bent on committing crimes against whites. After the conclusion of WWII, two major urban renewal projects destroyed large swaths of the African American community on the eastside, both Paradise Valley and Black Bottom. These forced removals were implemented by Mayors Albert Cobo (1950-1957) and Louis Miriani (1957-1961).

Nevertheless, African Americans resisted national oppression, institutional racism and national oppression through organizational efforts. Although most were initially excluded from trade unions on a racial basis numerous organizations were founded or enjoyed engagement with the Black masses. The Nation of Islam (NOI) was founded in Detroit in 1930. Later African Americans played a pivotal role in the UAW campaign to win recognition by Ford Motor Company in 1941.

Later in 1957 African American labor activists formed the Trade Union Leadership Council (TULC) which supported the struggle for Civil Rights in the South and the North. On the cultural front, Motown Records began in the late 1950s under the African American leadership of Berry and Esther Gordy. The music company grew to prominence during the early to mid-1960s.

The urban renewal program of the racist city administration directly impacted New Bethel Baptist Church and JVB Records located on Hastings. During the course of the 1950s, the African American community was slated for demolition under the guise of slum clearance. By 1961, most of the remaining neighborhoods and institutions were forced to relocate under imminent domain when they were later demolished for the construction of the Chrysler I-75 and Fisher Freeways. Tens of thousands of African Americans living in these communities moved further north and to the west side neighborhoods along 12th, 14th, Linwood and Dexter streets. Hundreds of small businesses, churches and social organizations were destroyed by the city administrations holding power in the 1950s and early 1960s.

New Bethel eventually re-located in 1963 through the repurposing of a large movie theater on Linwood and Philadelphia in the Virginia Park District. JVB Records re-opened up on 12th Street. The Virginia Park and surrounding communities, due to racial segregation policies in housing, was characterized by pockets of overcrowding in multiple-dwellings owned by absentee white landlords dividing up spacious apartments into additional units which were allowed to fall into disrepair.

City administration officials refused to enforce building codes designed for safety and quality of life in the Virginia Park District and other similar communities. Tensions escalated in the early 1960s prompting a radicalization of the African American people.

Aretha Franklin with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and her father Rev. C.L. Franklin in Detroit at Cobo Hall in 1968.

On June 23, 1963, the largest Civil Rights demonstration in U.S. history was held in Detroit along Woodward Avenue mobilizing hundreds of thousands of residents. The march was made possible by the role of Rev. Franklin along with an alliance of community organizations. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., President of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), had backed Franklin’s leadership role in the march mobilization. Franklin was very much involved in SCLC and advocated the elimination of racial discrimination in Detroit. King would deliver one of his early renditions of the “I Have a Dream” speech which was recorded and later issued by Motown Records.

Irrespective of these valiant nonviolent efforts, the general atmosphere became far more volatile as the predominantly white police force became notorious for their racial profiling, arbitrary arrests, brutality and murder of African Americans. By August 1966, the seeds of an urban rebellion occurred in the Kercheval Street area on the eastside. This rebellion was contained at the time.

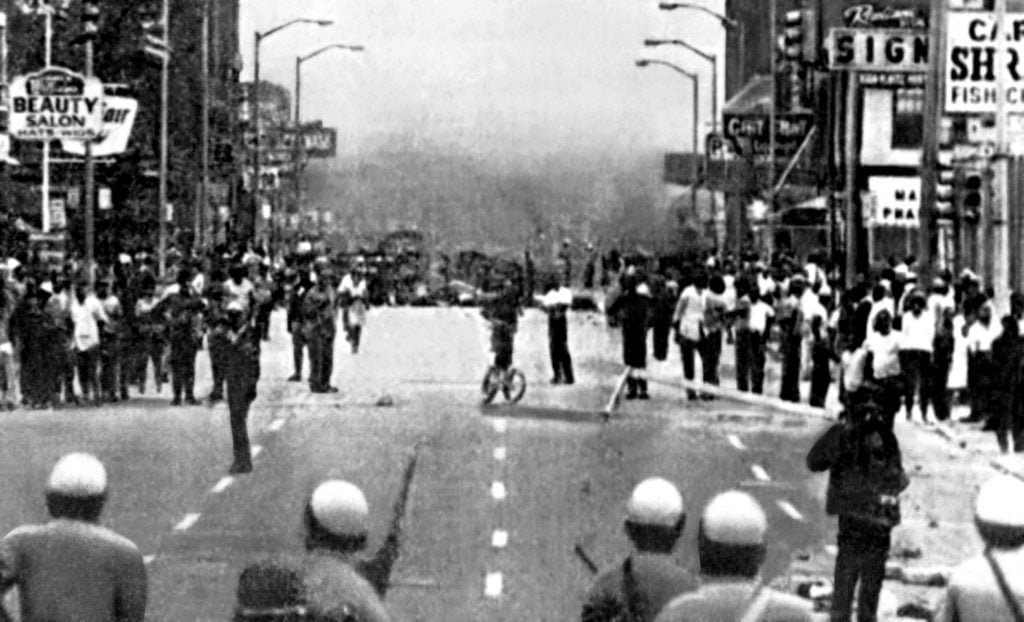

Nonetheless, the following year, on July 23, 1967, the largest urban rebellion up until that time in U.S. history, was led by African Americans having been sparked by a police raid on 12th Street in the early morning hours. The unrest continued for five days, when in the first 12 hours, the-then Democratic Liberal Mayor Jerome Cavanaugh and Republican Governor George Romney jointly agreed to send in thousands of National Guardsmen. By the second day of the rebellion, Romney appealed to Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson to send in 5,000 federal troops from the 82nd and 101st airborne division of the U.S. Army.

43 people were officially reported killed as a result of the July 1967 rebellion. That same year similar incidents of civil unrest occurred in over 160 cities according to the finding of the Johnson administration appointed National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorder. The Commission headed by Illinois Governor Otto Kerner concluded that billions in redevelopment funding was necessary to correct the problems of a divided society, one black and one white.

Johnson, facing a rebuke of his War on Poverty, Model Cities and Great Society programs from a coalition of both Republican and Democratic lawmakers refused to accept the findings of the Kerner Commission. In the aftermath of the Detroit rebellion other organizations were founded in Detroit which sought revolutionary solutions to the problems of national oppression and economic exploitation.

Detroit Rebellion July 23, 1967 at the corner of 12th Street and West Euclid

Two of the most well-known were the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement (DRUM), in 1968, which later expanded into the League of Revolutionary Black Workers (LRBW) the following year (1969). Also in late March 1968, the Provisional Government of the Republic of New Afrika (RNA) was formed in Detroit bringing together Black Nationalists and other revolutionary forces from around the country to demand the creation of a sovereign nation in five southern states.

New Bethel Baptist Church was located in the center of the 1967 rebellion where Linwood was the second hardest hit area second only to 12th Street. That same year, Aretha Franklin released her first album on Atlantic Records entitled “I’ve Never Loved a Man.” The album catapulted her meteoric career to new heights. That same year she was designated as the Queen of Soul at the age of 25.

The hit single “Respect”, written by the legendary Stax recording artist Otis Redding and later rearranged by Aretha, rose swiftly up the Rhythm and Blues and Pop Music charts in the spring and summer of 1967. The song was viewed as an anthem of resistance to the oppression of African Americans and women in particular. Aretha appeared on numerous local and national television programs. In early 1968, the city administration proclaimed a day of recognition for Aretha Franklin. She would later make a triumphant tour of Europe where she packed halls to the delight of Soul music fans throughout the continent.

Aretha’s older sister, Erma Franklin, and younger sibling, Carolyn, too enjoyed commercial success and recognition in the popular music field. The rise of Aretha and her sisters in the cultural arena further enhanced the celebrity status of Rev. C.L. Franklin.

Later in 1969, the RNA convened its second national conference at New Bethel Baptist Church on March 29. As the meeting was breaking up around 11:00pm that evening, a shooting incident involving Detroit police and RNA security forces took place outside of the church on Linwood. Two white police officers were shot, one fatally. Just a few minutes later, dozens of Detroit police entered New Bethel firing live ammunition at those leaving the RNA gathering. At least four people were wounded and approximately 150 were detained and taken to area police lock-ups.

Soon enough Rev. Franklin, Recorder’s Court Judge George Crockett, Jr., who had just been elected in 1966, and educator, real estate businessman and politician James Del Rio, went to the police stations where the arrestees were being held. None of them had been properly read their rights or charged with specific crimes. Judge Crockett held court in the police stations and released the detainees.

The shooting of the police officers and the subsequent release of the African Americans attending the RNA conference infuriated the white establishment in Detroit. A campaign by the corporate media, organized racists groupings and the police department sought to launch efforts to impeach Judge Crockett. The move to forced Crockett out of office failed as a broad coalition of political groups rallied under the banner of the Black United Front in defense of the community.

No one was ever convicted in the shooting and killing of the police officers in the trials that followed. Within the next four years, in response to vicious police misconduct emanating from a decoy unit called Stop the Robberies Enjoy Safe Streets (STRESS), the African American community mobilized behind the-then State Senator Coleman A. Young who became the first Black mayor of the city elected in November 1973.

Mayor Young relied on institutions such as New Bethel and the Shrine of the Black Madonna, formerly Central Congregational Church, pastored by the-then Black Power advocate and philosopher Rev. Albert B. Cleage, to secure his victory and a continuing political base for him to remain in office for the next two decades (1974-1994). Under the Young administration, significant reforms were enacted such as the implementation of an affirmative action program within the police department and among other municipal employees in general, championing African American political, proletarian and professional leadership. By 1977, Young had been re-elected easily for a second term being joined by a majority Black City Council including social democrats and Marxist lawyer turned politician Ken V. Cockrel, Sr.

Detroit was undoubtedly the leading center for African American political leadership on an official level as well as through interventions in the labor movement and grassroots community organizations. The heritage of African Americans and other national minorities were recognized through various cultural and political gatherings.

Contravening Forces and the Crisis in Modern Day Capitalism

These were times of monumental achievements for African Americans and women in the city of Detroit. However, other contradictory forces were in operation.

The restructuring of industrial production which began in the mid-to-late 1950s caused a drop in the city’s population. Plant closings, automation, the suburbanization of metropolitan Detroit, discrimination in lending and insurance policies fueled the outmigration from the city. Two major recessions in the mid-1970s and the early 1980s took their disproportionate toll on Detroit. Under the perceived progressive leadership of Young and the majority Black City Council, sizable levels of disinvestment was carried out against Detroit.

These aspects of the political and economic crisis in Detroit during the 1970s directly impacted New Bethel Baptist Church and Rev. Franklin in a deadly fashion. The rise in street crime and homicide rates gained Detroit the reputation as “The Murder Capital of the World.” Heroin was flooded into the African American communities breaking up families and neighborhoods.

In June 1979, the Franklin home on LaSalle Blvd. in the Virginia District, where the rebellion had begun just twelve years before, was broken into by burglars. Rev. Franklin was shot by assailants. He was left bleeding for an extended period of time before help arrived. While being treated in an area hospital he stopped breathing but was revived. Nevertheless, due to the loss of blood, the most prominent African American minister of the period suffered irreversible neurological damage. For the following five years of his life (1979-1984), Rev. Franklin was never able to speak let alone deliver a sermon. The golden voice of the Black Church was silenced.

Aretha, who was living in California at the time of the shooting, was forced to relocate back to Detroit to supervise, along with her siblings, other relatives and church members, the around the clock medical care for Franklin. He remained in his home until just a few days prior to his death. After being moved to a nursing home on Grand River on the west side, Franklin died in July 1984.

With the death of Rev. Franklin in 1984, the retirement of Mayor Young in early 1994, the continuing economic decline of the city of Detroit, many could ask: where is the Black Political Power movement in the city? The Great Recession of 2007 and beyond took a devastating toll on Detroit. The city was targeted through predatory lending by the financial institutions turning Detroit from being a municipality leading in home ownership for African Americans to its present-day status of a majority renter’s city. Homeownership, stable industrial and professional employment, had distinguished the African American community from other cities across the U.S.

Today in 2018, under a white corporate-imposed mayor from Livonia who came into office under questionable circumstances during an illegally crafted system of emergency management and bankruptcy (2013-2014), the largest municipal re-organization in U.S. history, the people of Detroit are still struggling against property tax foreclosures, poverty, substandard wages, a state-looted and beleaguered educational system, environmental degradation, government-facilitated tax captures for the benefit of multi-national corporations, among other issues.

Yet there remains a social and political determination to resist. In response to the severe illness and later death of Aretha Franklin, people have come out in their thousands to express sincere condolences and to evoke the memories of times past where the struggle for survival, equality, self-determination and political power took precedent over all other concerns. This is the genuine legacy of the Queen of Soul, the Franklin family, along with the African American people as a whole and their allies.

*

Abayomi Azikiwe is the editor of Pan-African News Wire. He is a frequent contributor to Global Research.

All images in this article are from the author.