Rewriting History: The Problem with Toppling Our Monuments

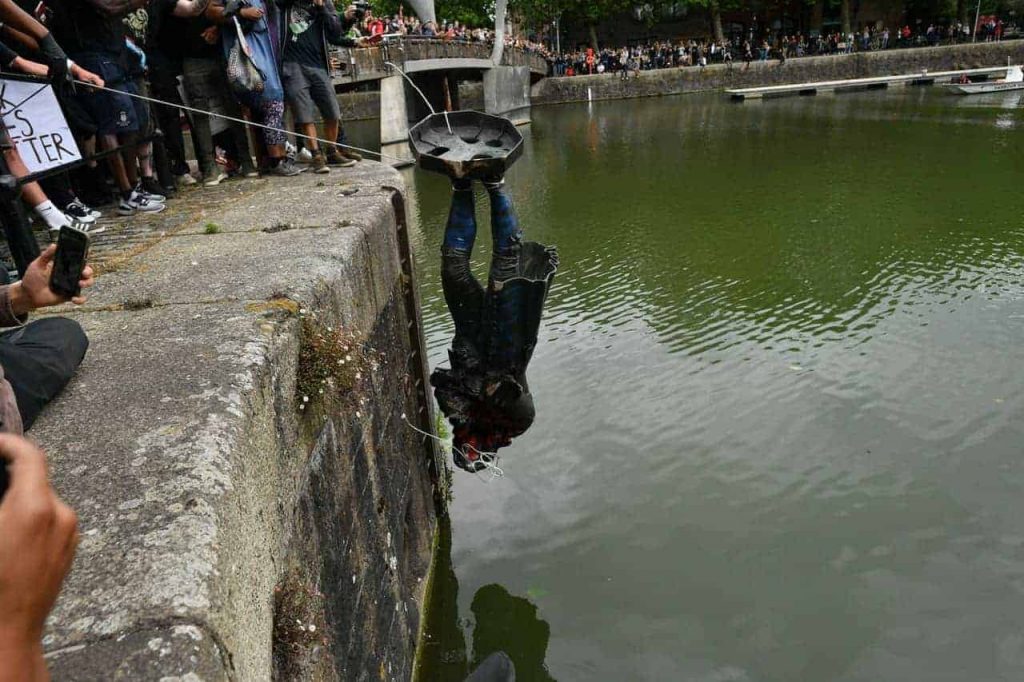

On Sunday a statue to the 19th century English merchant Edward Colston was seized from its pedestal and violently hurled into Bristol harbour by a group of protestors demonstrating as part of the Black Lives Matter movement. The incident has become the subject of fierce debate ever since. Edward Colston, like many wealthy Europeans of his time, was a slave trader, and the monument has become, for many, a symbol of racism of the type we must eradicate from our society for good.

The slave trade, which saw at least 12 million Africans shipped to North America over a period of 400 years, was a brutal, debased industry founded on the principle of putting profit before human rights. The money amassed from it went towards developing many of our renowned universities and institutions and the construction of towns and cities across the UK. But it was not only the Atlantic slave trade that contributed to our nation’s wealth. You cannot walk the streets of Britain today without noticing the hallmarks of our imperialist past. The British Empire exploited people from India to Barbados and the evidence of it is laid bare in the bricks and mortar of our urban architecture and street names. Our country is literally a museum to its imperialist past.

So, what are we to do, start tearing down our town halls, art galleries, and university buildings? How far are we to take the destruction of our material world in order to meet our contemporary standards? We have seen the attempt to rewrite history in recent years in Ukraine, for example, where Lenin statues have been toppled in a bid to wipe the Soviet leader and his Communist dogma, from the pages of history. Or in the Baltic states, where several monuments to the Red Army have been removed as a way of denouncing Soviet rule, despite their purpose being to celebrate victory over Nazism. The past, whether we like it or not, happened. It cannot be erased. There will always be statues that were on the wrong side of history; there will always be some who do not agree with the glorification of a particular figure.

Source: InfoBrics

In fact, it could be argued that we should retain controversial monuments as a constant reminder of past injustices. Better still, a more constructive approach would be to start building monuments, instead of removing them, to, for example, progressive 19th century thinkers who did stand up against slavery. Take the Scot, Zachery Macauley, governor of Sierra Leone and anti-slavery activist. Having initially been involved in the British sugar plantations in Jamaica at the age of 16, he devoted his life to fighting for the abolition of slavery, paving the way for the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act. There is a bust to him in Westminster Abbey but no statue as such. Surely a monument is long overdue.

Furthermore, it is vital that children are taught not only about the Atlantic slave trade, but all the sordid aspects of the western imperialist past. I say western, because it’s no secret that the whole of Europe was at it. The Dutch were exploiting Indonesia, the French were ransacking Africa and the Spanish pillaging South America. These were people of a different era, with a different way of thinking – call it primitive, or immoral or just plain wrong. Those that did follow a strong moral code were for the most part fervently religious and desperately trying to ‘convert’ conquered peoples to Christianity as they deemed them ‘savages’. Can we change these facts? No. The main thing is that we leave such attitudes in the past, where they belong.

Racism obviously remains a deep-rooted issue in the US which may take generations to eradicate. It is systemic and very much tied up with the country’s history, from the days when Europeans invaded the lands belonging to Native Americans. Unfortunately it is a nation founded on injustice and built on the blood, sweat and tears of exploitation. Although this should never be forgotten, what is even more important is learning from these mistakes. And so far, there is little evidence of this happening. For although the British empire has long been disbanded, Britain continues to support US imperialism and expansionism which wreaks havoc across the globe, from the wars waged in Iraq, Libya and Syria, to the multinational firms exploiting impoverished workers in Bangladesh and China.

Indeed, we may have come to terms with our role in the 19th century Atlantic slave trade in recent years, but we have a long way to go in recognizing our role in supporting the modern slave trade, which it is estimated involves a staggering 40.3 million people. That means 1 in 200 people worldwide is a slave. Whether we are talking about women and girls working in the sex trade in Asia or workers building the infrastructure for the 2022 Qatar world cup, slavery is far from being a thing of the past, it is part of the globalised world we live in. The clothing we wear, and the mobile phones we use, have more often than not been manufactured by people working in slavery or exploitation.

So while it may be easier to focus on monuments of the past which don’t comply with our moral standards, not only are we likely to be left with none at all, but we are at risk of deflecting attention from the real inequalities which plague our society. If we are indeed a more enlightened people than our forefathers, we need to look beyond the monuments on our streets, to the very food we put on our plates, how it got there, and who has been exploited for our benefit. Otherwise, if we’re pulling down a monument with one hand and swigging a Starbucks coffee (made from beans harvested by slave labour) with the other, then we’re simply hypocrites.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

This article was originally published on InfoBrics.

Johanna Ross is a journalist based in Edinburgh, Scotland.