Revealed: Internal Discussions Between Ministry of Defence and Regulators on Flying Predator Drones in UK

Details of discussions between the Ministry of Defence (MoD) and the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) on plans to allow the RAF’s upgraded version of the US Predator drone to be flown within the UK have been released following a Freedom of Information request by Drone Wars UK. More than 200 pages of internal documents including emails, minutes of meetings, discussion papers and copies of slide presentations have been released. Many of the documents have been redacted, some extremely heavily.

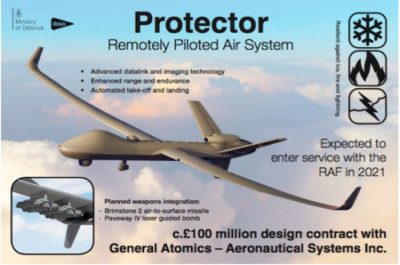

David Cameron announced in October 2015 that the Britain was to purchase the new version of the Predator, which the UK is re-naming as ‘Protector’. The UK’s current type of armed unmanned aerial vehicles, the Reaper, are unable to be flown in the UK due to safety issues and the new version was purchased, in part, to enable the RAF to fly its large armed drones within the UK for training as well as security and civil contingency purposes.

The documents being published today by Drone Wars are dated between January 2016 and February 2017 and are related to a series of meetings between MoD officials, RAF officers, the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA), the Military Aviation Authority (MAA) as well as the US drone manufacturer, General Atomics. The papers show the MoD struggling to convince civil regulators that the new drone can safely be flown across all UK airspace. While discussions appear to be on-going (the release only includes papers up until February 2017), it seems likely that the drone will be restricted in where it can fly until regulators are convinced that technology and procedures are sufficiently developed to make it safe for unmanned and manned systems to fly together.

There is little sign in the papers of anyone suggesting the need for a proper parliamentary or public debate about the implications and impact of flying large military drones within the UK other than the acceptance of a need for a “communications strategy” to persuade the public to accept such flights.

Challenges

Soon after the purchase of the new drone was announced, the MoD realised that General Atomics (GA-ASI) did not quite understand the UK situation and suggested bringing a number of people together to go through the issues with them. An MoD official emailed colleagues in January 2016:

“During the PROTECTOR Type Board Meeting at the end of last year … it was identified that GA-ASI needed better to understand the UK requirements and intent for operating PROTECTOR, and the associated constraints in the UK; in order for them to be able to progress design, certification and qualification aspects of the Project. It was decided that an Airspace Integration Workshop, in the UK, would be the best vehicle to gather the broad range of subject experts from the stakeholder community to achieve this.” (MoD official, 12 Jan 2016)

This ‘Protector Airspace Integration Workshop’ was to become the first of a number of meetings and telephone conferences about this issue involving the CAA, the MoD and General Atomics.

Slide from ‘Protector Briefing Pack’ prepared for telephone conference between MoD/CAA and FAA/USAF/General Atomics, 25 April 2016. [Click image to open full briefing pack]

Detect and Avoid

While the new drone is being specifically built to NATO’s ‘STANAG 4671’ quality in order that it is of the minimum standard of airworthiness to be able to be ‘certified’ by aviation authorities, as the CAA makes clear being built to basic airworthiness standard does not mean regulators will accept that the aircraft is able to fly anywhere in the UK .

Along with other air regulators around the globe, the CAA require that at a minimum, aircraft should be able to ‘see and avoid’ danger in unsegregated airspace. As there is no pilot on board to physically comply with this basic rule of the air, drone manufacturers need to develop a technological solutions. Various ‘sense and avoid’ or ‘detect and avoid’ systems are being developed and marketed, but have yet to prove themselves. As the CAA stated in one of the first meetings, “remote controlled equipment is not considered acceptable for use as a Detect and Avoid solution.” Minutes of a meeting in April 2016 acknowledge that “technological advances would need to occur in parallel with regulatory developments to enable Protector to operate in UK airspace…”

The day after the meeting, a CAA official sent an email stating:

“I have consistently made clear that the CAA cannot start getting deeply involved in matters regarding what equipment fit/requirement/capabilities/standards that Protector needs as it’s not our call to make – we can outline the principles, in that our basic questions will always be how are you going to mitigate for the potential of a collision (with anything)?” [CAA official, 19 April 2016]

Reading between the lines (and the redacted sections) there appears to have been a desire by some in the military camp, perhaps being pushed by General Atomics, to press ahead and cut through what it perhaps saw as bureaucratic red tape. A suggested solution (the specific details of which has been redacted from the papers) was advanced by the military which did not impress the airspace regulators. A CAA official, reporting back to his colleagues, wrote that he had expressed his “lack of confidence” with the solution and made clear to them “the novel and ground breaking nature” of what they proposing. As many will remember from ‘Yes, Minister’, this is a polite, but damning verdict from civil servants.

Plan B

Tweet from Air Marshall Julian Young, August 2017

While not giving up on their technological solution, the scepticism of the regulators indicated to the military contingent that they also needed a ‘Plan B’. According to the papers, this consisted of accepting that Protector would only fly in certain types of airspace (UK airspace is divided into different categories, see here for an explanation) but also making changes to the current airspace structure (known as Airspace Change Proposal – ACP) to put in some segregated corridors where the drone could fly, away from manned aircraft. However, as one of the internal documents makes clear, there are implications for others with Plan B:

“If RPAS integration cannot be achieved, then segregation via ACP will be necessary. This will incur additional cost and delay, and could impose restrictions on other UK airspace users.” (Document: Asst Chief of Air Staff, Protector UK Airspace Integration, 20 May 2016)

One of the segregated corridors will likely be from the drone’s UK base to the airspace where it will be allowed to fly. The covering letter from the CAA, in response to Drone Wars FoI request, states that the proposed location to base the drones was exempt from disclosure:

“The MOD has not formally decided where the Protector UAV will be based, which will be a decision that will be approved by Ministers. The CAA considers that it would not be reasonable or sensible to disclose information about the likely outcome at this stage until the decision has been finalised. The location of the Protector’s base will be confirmed by the MOD in due course.”

However it is likely that the drones will be based at RAF Waddington in Lincolnshire as that is where the RAF’s key ISTAR (Intelligence, Surveillance, Target Acquisition and Reconnaissance) capabilities are based, including Reaper pilots controlling the UK’s armed drones overseas. Several of the papers indicate that Waddington could well be the location of the new drones. It should also be noted that there are two air-to-ground firing ranges in Lincolnshire that could be used for drone strike training.

Persuading the public on Protector

From the papers released it’s clear that the MoD appreciated that the need to persuade the public that having large military drones flying in the UK is both safe and acceptable. The MoD has frequently expressed its annoyance at the negative public perception of drones and has several times engaged in PR exercises in an attempt to change how they are viewed.

In a paper prepared for one the meetings in May 2016, this issue was highlighted: “Public perception will be central to normalising RPAS [drones] use in UK airspace, especially for military purposes.” The paper concludes:

“While… the broader economic and reputational benefits for the MOD and Prosperity Agenda may be compelling… the perception of RPAS – both by the public and the ATM [air traffic management] community – will be central to integration and require a coherent cross-government communications strategy.”

The frustration will the ‘ATM community’ was apparent in a report written by a military officer following his visit to an International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) symposium in Switzerland in May 2016. Civil aviation organisations are “overwhelmed” with issues arising from small drone use, say the officer, and are looking to industry to present solutions to enable large drones to be integrated. This, he argues, “presents an opportunity for the military to assume a degree of leadership in RPAS regulatory standards via industry.” He goes on:

“If appropriately highlighted by Centre, the associated technological and commercial benefits to be derived from integrating military and commercial RPAS into airspace may also prove a powerful lever to assure Protector timescales and funding.”

Slide from ‘Protector: Airspace Access Strategy Briefing – Feb 2017’. Note indicates Protector will fly from RAF Waddington to Class A-C airspace. [Click to see full briefing]

MAA takes over from CAA

Reading through the papers it’s hard not to see a gap in culture and understanding between the civil regulators and the military. At some point it is suggested that it will be better for the Protector team to deal solely with the Military Aviation Authority (MAA) and then for the MAA to deal with the CAA when needed. A memo notes: “It was agreed that in order to clearly delineate the boundaries of responsibility, the PROTECTOR team would not deal directly with the CAA, but rather through the MAA.”

This suggestion seems to have been enthusiastically accepted by all parties and correspondence with the CAA comes to an end in February 2017. An email from the CAA to Drone Wars in January 2018 stated:

“I can confirm that the CAA has not had any email exchanges/discussions with the MoD or RAF about the Protector since February 2017. It is important to note that this is a military programme and does not fall under the regulatory remit of the CAA as we are responsible for the regulation of civilian aviation. The MoD regulates its own flying activities (through the Military Aviation Authority) and so we will only get involved if requested.”

Despite this disavowal of responsibility, as the minutes of one of the last meetings included in the papers details:

“If the interim Proposal fails [this is likely the use of a Detect and Avoid technology] then PROTECTOR [redacted] will need to be achieved through segregated airspace and ACP [Airspace Change Proposal]. The last safe moment for ACP establishment (to still meet PROTECTOR initial operating capability) is December 2018.”

Airspace Change Proposals are made to the CAA and must be agreed by them.

Public debate needed

The papers give a valuable insight into what is going on behind the scenes on this issue. What is stark is that there is no discussion about the need for proper parliamentary or public debate on the implications or impact of flying large military drones in UK airspace even though CAA representatives express clear reservations about whether technological solutions will provide the right level of safety for the public. It should be noted that large military drones regularly crash on training flights in the US as well as on operations overseas.

Aside from the obvious safety issues, once Protector drones are flying within the UK, it is possible that they could be used by what is discreetly called ‘Other Government Departments‘ for security operations within the UK. Reaper drones operated by the UK currently undertake surveillance and reconnaissance operations against terrorist suspects overseas. It is not that much of a leap to imagine them being used in that way here in the UK. It is surely right that the implication of this – and what the limitations are – should be openly discussed and debated.

The forthcoming ‘communications strategy’ to persuade us of the need to have large military drones flying over our heads must be challenged. PR is no substitute for proper debate and discussion on this important issue.

*

All images in this article are from the author unless otherwise stated.