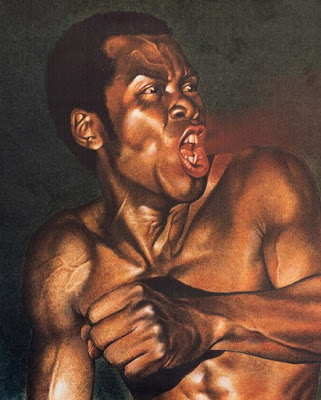

Remembering Fela Anikulapo Kuti – Revolutionary African Musician

Featured image: “Roar”. A portrait of Fela Anikulapo Kuti by Colombian-born artist Heriberto Cogollo (Source: Adeyinka Makinde)

Fela Kuti was a revolutionary African musician, the inventor of a genre which he called ‘Afro-Beat’ and the scourge of successive military dictatorships and civilian governments whose misrule of Nigeria has blighted the development of Africa’s most populated country. Fela was an iconoclast who challenged the powerful in society, a rebel whose bohemian lifestyle traversed the boundaries of socially prescribed behaviour as well as a social commentator whose lyrics, often suffused with coruscating barbs and comical vignettes, laid bare the daily tragedy of the lives of the suffering African proletariat. His death twenty years ago was mourned by millions of his countrymen and his legacy of social activism, critique of Nigeria’s governance as well as his Pan-Africanist aspirations remain as valid today as they did at the time of his passing.

Fela was born into the upper-middle class elite of colonial-era Nigerian society in the Yoruba city of Abeokuta. The first part of his original hyphenated surname, Ransome-Kuti, was bestowed on his grandfather Josiah Jesse Kuti, an Anglican clergyman, by an English benefactor. Josiah was a talented composer of Christian hymns and a church organist. Fela’s father, Israel Ransome-Kuti was a prominent educator and his mother, Funmilayo Kuti was a feminist and social activist with Marxist leanings who was part of several national delegations representing Nigeria at conferences which were designed to set out a pathway to independence from Britain. It is from these antecedents that Fela’s talent for music, a predisposition to rebel and his interest in politics and the plight of the ordinary person stem.

Fela formed his first band Koola Lobitos in London when studying at Trinity College of Music where he enrolled in 1958. He learned classical music by day and played the trumpet at nightly and weekend gigs which catered to the tastes of Britain’s West African and Afro-Caribbean communities. He played conventional West African-style highlife music: songs about love and the mundanities of everyday life. It was a style he continued with on his return to Nigeria in 1963 right through to the period of the Nigerian Civil War when most of the federation was pitted against the secessionist state of Biafra in a bloody civil war that raged between 1967 and 1970.

It was not until he embarked on a tour of the United States during the war that Fela’s music and his raison d’etre undertook a radical shift. His association with Sandra Isidore, a black American immersed in the politics of the Black Panther Party and the growing drift towards Afrocentricity, ignited in Fela a new vision that involved integrating black politics with a hybrid style composed of contemporary horn-driven Afro-American popular music, psychedelic rock and the African rhythmic cadences of vocal and instrumental expression. A key part of this musical expression was the drumming of Tony Oladipo Allen whose input first in regard to an increasingly jazzified element to the music of Koola Lobitos and then with the new breed of politicised and funked-up music qualify him as being the co-creator of Afro-Beat.

The musical rebirth led to Fela renaming his band the Africa 70. American funk and soul collided with Yoruban rhythms which were accompanied by lyrics layered with Pan-Africanist sentiment. Fela’s new model sound, a symbiosis of Afro-Diasporan elements, sounded fresh but also natural. The Yoruba culture is one which is highly syncretic in nature.

The new bent towards protest singing was also consistent with Yoruban modes of expression. In contrast to the praise-singing directed at the wealthy and the important in traditional society was abuse-singing. Fela’s Yabis songs which ridiculed and denigrated the rich and powerful in Nigerian society would form the backdrop to many popular compositions as well as a multitude of iron-fisted reprisals from the authorities. His popularity markedly increased as the 1970s developed and his audience ravenously anticipated his next incendiary epistle on long-playing vinyl.

Fela lampooned the the high-handedness of police officers and soldiers in “Alagbon Close” and “Zombie”. His disdain for the ‘foreign imported’ religions of Christianity and Islam and his belief that they served as an opiate for the masses was reflected in “Shuffering and Shmiling”. He criticized middle class Nigerian aping of Western mannerisms in “Gentleman” and mocked African females who bleached their skin in “Yellow Fever”. His uncompromising position on eschewing the colonial-derived mentality and promoting black pride formed the backdrop to his dropping ‘Ransome’ from his surname. In its stead, he adopted the name ‘Anikulapo’ which means “he who carries death in his pouch”.

He had established his pan-African outlook via his album “Why Black Man Dey Suffer” in 1971 but when criticising the racist regimes of Rhodesia and South Africa in songs like “Sorrow, Tears and Blood” and “Beasts of No Nation”, did not fail to remind his listeners of the hypocrisy and the brutality of Nigeria’s military rulers. He sang against imperialism and neocolonialism while pointing out that he felt certain of Nigeria’s elite such as the wealthy businessman, Moshood Abiola were agents of the Central Intelligence Agency. Abiola, who rose to be the Vice President of the African and Middle Eastern region of the International Telephone and Telegraph company (IT&T), was lambasted in the song “ITT (International Thief Thief)” in a diatribe against the exploitation of Africa by multinational companies and the African ‘big men’ who aid them in this endeavour.

Corruption and the inhumanity of Nigeria’s elites were a consistent topic for Fela in his recordings, his stage banter at his popular club ‘The Shrine’ and in his frequent utterances to the press. When Nigeria hosted the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture in 1977, he refused to perform at the gathering in protest at the corruption surrounding the event. “Money is not Nigeria’s problem”, the overthrown General Yakubu Gowon had said a few years before, “it is how to spend it.” And ‘Festac’, the abbreviated name of the festival, had induced a wild spending spree by the Nigerian government which proceeded with the obligatory backhanders for organising officials.

The bringing together of artistic talent from Africa and the African Diaspora had appealed to the Pan-Africanist sentiments of Fela who as a young boy had been introduced to its greatest champion, Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah, by his mother. He felt that the gathering could be used to “redirect the thinking of the common man”. He had been invited to join the National Participation Committee for Festac along with other luminaries from Nigerian drama, music and literature, including his cousin the future Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka, but along with Soyinka and a few others withdrew disillusioned.

When the festival commenced, Fela denounced the military government in nightly sermons delivered at ‘The Shrine’ where musicians flocked to pay him homage. Among them were Stevie Wonder, Sun Ra and Hugh Masekela. The Brazilian artists Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil who for a time had been forced into exile by the military junta of their country also met Fela.

Fela would pay a heavy price for his harangues. Less than a week after the end of the festival, the army surrounded his commune, known as the Kalakuta Republic, before storming it. Its inhabitants, not least Fela were beaten and the female members of his entourage sexually violated. Fela’s mother who resided at the residence was thrown from a first floor window and although initially surviving the attack died a few months later from injuries that she sustained.

It was a dark period for Fela. He spent 27 days in jail and suffered different bone fractures. He was put on trial and an official inquiry whitewashed the invasion and destruction of his compound concluding that the damage to his property had been perpetrated by “an exasperated and unknown soldier”. To top it all off Fela was branded a “hooligan”.

He went into temporary exile in Ghana and responded with lamentations of his experiences with the songs “Sorrow, Tears and Blood” and “Unknown Soldier”. In the former, Fela rails in his trademark pidgin English which was readily accessible to the common person:

So policeman go slap your face

You no go talk

Army man go whip your yansh (buttocks)

You go dey look like donkey

Fela’s allusion to Army brutality, a common occurrence in 1970s military-ruled Nigeria, carried a resonance among the many civilian victims who had been verbally humiliated, maimed and even killed by soldiers.

Yet Fela remained defiant. He partook in a traditional marriage ceremony with his entire female entourage of 27, performed at the Berlin Jazz Festival in 1978 and in anticipation of the first civilian elections to be held in Nigeria since the middle 1960s, he formed a political party, the Movement of the People Party, and offered himself as a presidential candidate in 1979.

Fela continued to release music and embarked on many tours of European and American cities gaining a wider audience and respect from members of the rock community. He had known Ginger Baker, famous as the drummer for the 1960s blues-rock trio Cream, during his sojourn in England in the 1960s and both men collaborated in the 1970s and met each other frequently while Baker was resident in Nigeria from 1970 to 1976.

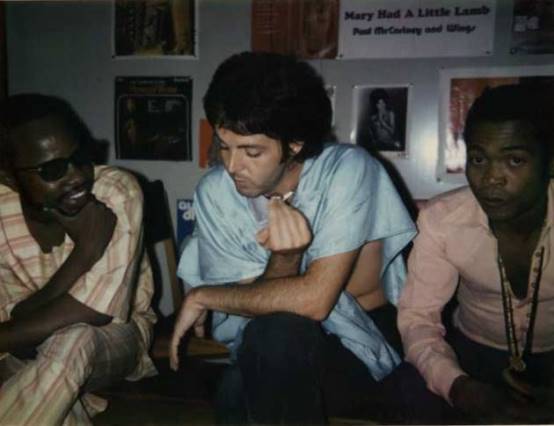

Paul McCartney and Fela Kuti (Source: okayafrica)

Paul McCartney was introduced to Fela when he went to Nigeria to record his album ‘Band on the Run’. After an awkward first meeting that had Fela accusing McCartney of coming to Africa to “steal the Black man’s music”, both men developed a friendship. McCartney would later confess to have been reduced to tears by the power of Fela’s music. In his autobiography published in 1989, Miles Davis acknowledged Fela as a force in music.

Fela would continue to endure numerous arrests: many of them for possession of Indian Hemp but also one last major politically-motivated arrest in 1984 which involved an alleged violation of currency regulations just before he was due to embark on a tour of the United States. His detention under the military regime which had overthrown the civilian government that had been elected in 1979 led to an international campaign spearheaded by Amnesty International to free him. Soon after his release in 1986, he played alongside artists such as U2, Sting and Peter Gabriel in a series of benefit concerts for Amnesty.

Over a million people turned out for his funeral after a lengthy illness. His brother Olukoye, a medical practitioner, announced that Fela had stubbornly refused to seek medical help and that by the time he agreed to be taken to hospital was not cognizant of the diagnosis of AIDS.

The cause of death many blamed on a hedonistic lifestyle. The image he frequently portrayed in songs and interviews of a playboy were real enough. Alongside the praise he earned from many of his country men were the denunciations of others. During his life he was criticised for corrupting the nation’s youth due to his fondness for marijuana and his projection of hypersexuality. While he may have spoken up for the nation’s downtrodden underclass, Fela was attacked for exploiting young women many of who came from poor backgrounds. The accusations of misogyny where often backed up by evidence of his living arrangements, the interviews that he gave as well as songs such as “Mattress”.

He was a mass of contradictions. While he may have spoken out against dictators, he ruled his commune in an authoritarian manner. And even the atrocity committed against him by the soldiers ransacking of his home was preceded by an incident in which a number of his employees had a violent confrontation with some soldiers during which they appropriated a motorcycle and later set it on fire. For some, Fela had set him set above the law from openly smoking weed on stage to holding up traffic while he crossed the road on his pet donkey.

Fela was uncompromising. In the early part of his career he turned down offers from foreign record companies to market Afro-Beat to Western audiences in the way reggae music was because it would have meant that he have to shorten the length of his songs. Later on he prevaricated over signing a one million dollar deal with Motown records until the offer lapsed. He could have chosen to live a relatively comfortable existence in European exile in a city such as London or Paris but that was never an option.

He had several distinct nicknames each reflecting a part of his multifaceted personage. ‘Omo Iya Aje’, which translated from Yoruba means the son of a witch, alluded to the belief that Fela inherited supernatural powers from his mother, in her prime a powerful female figure. Fela’s unusual disposition and rejection of convention earned him the sobriquet ‘Abami Eda’ (Strange creature). He was the ‘Chief Priest’ because of his practice of traditional Yoruba religious rites which were featured during his performances at the Shrine. Finally, the ‘Black President’ was an acknowledgement of his leadership qualities and his promotion of ‘Blackism’ and Pan-Africanism.

Now fully two decades after his passing, Fela’s music and the message in his music continue to resonate. His records still sell and his life story has been retold in several biographies and through a successful Broadway play “Fela!” He was more than a musician simply because his protest songs were not merely abstractions confined to the music studio or to music festivals. He transcended the role of a conventional musician because he spoke to the masses and confronted successive military dictators at great cost.

Wrote Lindsay Barrett, a Jamaican-born naturalised Nigerian novelist:

“It is no exaggeration to say that Fela’s memory will always symbolise the spirit of truth for a vast number of struggling people in Africa and beyond.”

Fela Kuti was born on October 15th 1938 and died on August 2nd 1997.

Adeyinka Makinde is a London-based writer. He can be followed on Twitter @AdeyinkaMakinde