Remembering Cuba’s Commitment to Angola’s Liberation Movement

Cuban blood left its stamp on the conscience of the world after the Angolan Wars of 1975-1988. Corporate politicians are united in their desire for us to ignore this reality.

Fed up with foreign wars, Portuguese officers overthrew Prime Minister Marcello Caetano on April 25, 1974. Many former colonies had the opportunity to define their own future.

Angola had been the richest of Portuguese colonies, with major production in coffee, diamonds, iron ore and oil. Of the former colonies, it had the largest white population, which numbered 320,000 of about 6.4 million. When 90% of its white population fled in 1974, Angola lost most of its skilled labor.

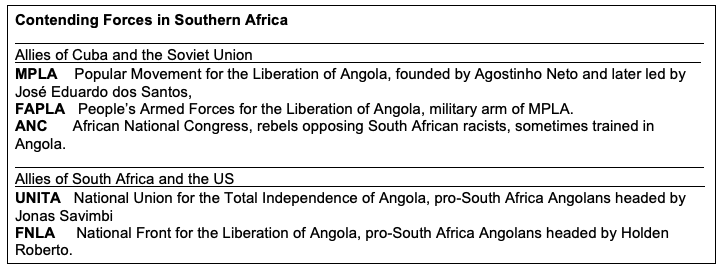

Three groups juggled for power. The Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), headed by Agostinho Neto was the only progressive alternative. The National Front for the Liberation of Angola (NFLA), led by Holden Roberto, gained support from Zaire’s right-wing Joseph Mobutu, a conspirator in the assassination of Patrice Lumumba. Jonas Savimbi, who ran the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), worked hand-in-hand with South Africa’s apartheid regime.

Portugal told South Africa to remove its troops from Angola, which it did by October, 1974. Recently defeated in Viet Nam, the US felt unable to send troops. Encouraged by the Ford administration South Africa returned to Angola within a year.

Meanwhile, Fidel Castro’s representatives met with Neto along with the head of MPLA’s recently organized militia, the Popular Armed Forces for the Liberation of Angola (FAPLA). Not eager to intervene, Cuba declined to give financial support.

The South African invasion began October 14 when many of its white troops pretended to be UNITA forces by darkening their faces with “Black Is Beautiful” camouflage cream. By November, Fidel knew that without help the Angolan capital would fall to apartheid forces and he approved military assistance. The small number of Cubans who arrived were critical in stopping the South African drive to Angola’s capital, Luanda.

Intense hostility between UNITA and the FNLA resulted in the latter being crushed by early 1976, simplifying the conflict to battles between the MPLA and UNITA, with their allies. Cuban troops reached the southern border with Namibia, completely pushing out the forces of apartheid.

Multiple factors propelled Cuba’s entry. The 1959 revolution was so intensely opposed by the US that it became clear that the best defense of Cuba would be an offense. A campaign in Africa would be less likely to provoke a direct confrontation, largely because most Americans did not see Africa as part of their backyard. A huge number of Cubans are of African descent and revolutionaries saw anti-racism as core to their politics. Fidel referred to the anti-apartheid struggle as “the most beautiful cause.”

The second phase of war

Since the fighting seemed to decrease, the number of Cuban soldiers in Angola dropped from 36,000 in April 1976 to under 24,000 within a year. However, when France and Belgium sent troops to Zaire, Cuba halted its troop withdrawal.

Throughout the Angolan conflict, South Africa and the US ignored international law and acted as if it was perfectly natural for South Africa to dominate Namibia. After South African planes massacred Namibian refuges at the Cassinga camp in Angola in May 1975 US President Jimmy Carter brushed it aside and quipped that “we hope it’s all over.”

Memories of that massacre stayed in the mind of a 12 year old girl, Sophia Ndeitungo: “The first Cubans I ever saw were the soldiers who came” to rescue them. Most Cubans were white, so she “…thought they were South Africans. Later, we understood that not all whites are bad.” Sophia was relocated to Cuba’s Isle of Youth to study. She graduated from Havana’s medical school, married another Cassingan refugee, returned to Namibia, and became head of its armed forces medical services in 2007. For thousands of black Africans, Cubans were the only white people who showed them any kindness.

Exuberant over the 1980 US election of Ronald Reagan, South Africa stepped up its raids in Angola, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Lesotho, Swaziland, and Botswana. In August 1981 South Africa poured 4000 to 5000 troops into southern Angola with tanks and air support. It expanded tactics to include poisoning wells, killing livestock and destroying food distribution and communications. It was in this context that Cuba began sending 9000 troops back to Angola during August 1983.

Savimbi: Ally of US and South Africa

Throughout the Carter administration and the early Reagan years, the US increased its flow of weapons to UNITA. As early as 1974 UNITA’s leader Savimbi had established contacts with the Portuguese dictatorship and promised South Africa that he would help them build an anti-communist bloc. Savimbi spoke fluent English, oozed self-confidence, cleverly manipulated his audience, knew just what Americans wanted to hear, and was “without scruple.” In other words, his combination of qualities was a perfect fit for a CIA front man.

Savimbi consolidated his local power by executing village opponents as “sorcerers.” He had total control and did not tolerate dissent. By 1980, in addition to ridding UNITA of those who challenged him, Savimbi had “…the wives and children of the dissenters burned alive in public displays to teach the others.”

Special Forces Colonel Jan Breytenbach saw Savimbi as a “manipulator extraordinaire … As a political leader, he was very good. I would compare him to Hitler.” This comparison to Hitler was not a slighting of Savimbi – it was a compliment, as multiple top South African politicians had been members of pro-Nazi groups.

Among those who overlooked Savimbi’s campaigns of mass destruction was President Jimmy Carter, who took time out of his schedule of human rights advocacy to arrange the flow of secret US dollars to UNITA. In 1985 Steve Weissman summed up attitudes that spanned both parties: “We wanted to hurt Cuba, and we wanted to help people who wanted to hurt Cuba. When Savimbi said that he was ‘fighting for freedom against Cuba’ – this was his trump card. It was impossible to counter it. Savimbi had one redeeming quality: he killed Cubans.”

South African attitudes toward Savimbi fit into its broader perspective of utter contempt for blacks. Deaths of whites were followed by announcements from the army and newspaper obituaries in the press. Deaths of black soldiers were not broadcast either by their military superiors or by the press at home.

South African views mirrored those of US politicians. A 1971 amendment to the US sanctions bill by former KKK member and Democrat Senator Harry F. Byrd (VA) exempted chrome, thereby pulling all teeth from consequences to the white minority government of Rhodesia. A much-publicized July 1986 speech by Reagan lavished praise on South African whites who he said gave great opportunity to blacks.

Conflicts between allies

Considerable discord between allies arose from the marriage of necessity between Cuba and the Soviet Union. Cuba’s strategy had been for it to confront the better armed and trained South African forces and for Angola’s FAPLA to counter internal enemies in guerrilla warfare. The Soviets believed that FAPLA should develop a conventional army with tanks and heavy weapons to fight South Africa.

But Angolan troops had virtually no formal education. Officers might have reached the second, third or fourth grade, but the army’s rank and file typically had never been to school and were unable to master sophisticated weapons provided by the Soviets.

While Cuba advocated FAPLA’s concentrating on UNITA, it simultaneously cautioned that the Angolan military should have Cuban backup whenever venturing into territory largely surrounded by UNITA and South African troops. President Neto died in September 1979 and his successor, José Eduardo dos Santos, was often lured by Soviet visions of having a conventional army strong enough to overcome both opposition forces.

Throughout the conflict, the Soviets acted as if the primary weapons of war were logistical plans, tanks and weapons, while for Cuba the maps of war were drawn from the hearts and minds of those who used these weapons. Cuba understood that the Angolan front was part of a broad campaign against racist domination across southern Africa.

By March 1976, Cuba’s initial victory over South Africa let loose a “tidal wave” against white racist rule as blacks became joyfully aware that apartheid forces were vulnerable. In September 1977 Steve Biko died in police custody and within a month the government had banned 18 organizations and the most important black newspaper. In September 1984 a new South African constitution bestowed political participation upon “coloreds” and Indians while denying the same rights to blacks. Black townships in the industrial centers of the country exploded. Massive demonstrations, strikes, school walkouts and boycotts of white owned stores spread like wildfire. Soon funerals for victims of state repression were added to the events.

The ceremony for awarding the Noble Peace Prize to Bishop Desmond Tutu drew a huge rally. Open opposition to apartheid mushroomed hand-in-hand with intensification of the war in Angola. By 1987 the South African demonstrations were so large that thousands of white solders were assisting police within its borders.

Soviets were generally aloof from those they came to protect. Africans themselves noticed how quickly Cuban soldiers, doctors, and others stationed near them melded into their society. One recruit remembered that “The Cubans ate what we ate, slept in tents like us, lived as we did.’” Physician Oscar Mena described his work in Angola as a “beautiful experience.” Soviets in Angola seemed to think of it more as a job. Battlefields reflected the cultural chasm – Soviet advisers stood on the sidelines of fighting while Cubans always joined in combat.

Dancing barefoot on a razor’s edge

In 1985 the Soviets persuaded Angola to attack UNITA’s stronghold in Mavinga, despite dire warnings from Havana that they would have to go through an area controlled by UNITA and create a supply line that it could not possibly defend. It met with a disastrous defeat. The same tragedy was repeated in 1987.

Afterwards, South Africa’s General Geldenhuys boasted of its victory to the press, which sparked intense global repudiation since that country had claimed non-involvement in Angola. Was the time now ripe for Cuba to launch an all-out attack on South Africa’s forces? This decision had Fidel dancing on a razor’s edge.

The most delicate balancing act was with the Soviet Union. Without its financial aid, Cuba could not carry out the war. Without its donation of military supplies, Angola’s FAPLA would be unable to fight. But its repeated bungling of strategic decisions threatened every aspect of the war.

No less sensitive was Angola, which seemed mired in corruption. Yet, the MPLA government was vastly superior to whatever Savimbi would usher in. A victory in Angola would strike a mortal blow into the heart of apartheid; but, Cuba could not go forward without approval from Luanda.

Cuba had saved its most powerful weapons for self-protection in the event of a US invasion. As Cubans drew weary of a decade and a half of sacrifice, Fidel and Raúl knew that being too cautious might mean missing an opportunity that would never repeat itself. However, moving too quickly could cause a defeat that would demoralize and exhaust the Cuban troops, doctors, and people at home.

They also knew that thousands of white soldiers became unavailable for service in Angola because they were needed in South Africa to suppress dissent. Reagan’s embroilment in the Iran-Contra scandal left the US unable to go on an attack.

Cuba’s leaders agreed that the hour had arrived to send vastly more troops and arms to Angola, including its best planes, its best pilots and its most sophisticated weapons. In March 1988 FAPLA and Cuba defended the town of Cuito Cuanavale as it was attacked by South African and UNITA troops. Enough Cuban planes and pilots had arrived for them to score a victory in the air. At the same time Angolan troops drove back the ground attack. South African troops were demoralized as it signaled the beginning of the end. Nelson Mandela observed that this key battle “destroyed the myth of the invincibility of the white oppressor.”

Despite the clear defeat of apartheid forces, US diplomats continued to tell their Soviet counterparts that South Africa would not leave Angola until all Cuban troops were gone. Fidel told the Soviet negotiator to “… ask the Americans why has the army of the superior race been unable to take Cuito, which is defended by blacks and mulattoes from Angola and the Caribbean?”

Cuban negotiator Risquet politely told them “The South Africans must understand that they will not win at this table what they have failed to win on the battlefield.” Knowing that a full invasion of Angola would be rebuffed internationally, result in thousands of casualties, and potentially leave the country unable to defend itself from internal black rebellion, South African politicians gave the nod to its commanders to leave. Its troops were withdrawn from Angola by August 30, 1988.

In Angolan elections dos Santos of the MPLA defeated Savimbi (49.8% to 40.1%). In April 1990 South African president Frederick de Klerk legalized the African National Congress and South African Communist Party as he freed Nelson Mandela, who was elected to head the country in April 1994.

Many of the parallels between the US in Viet Nam and Cuba in Angola were striking and both foreign interventions had a profound effect on public consciousness. Yet, Cuba was defending an actual country from invasion while the division of Viet Nam into “North” and “South” was a figment of the imaginations of French and Americans, which is to say that no foreign invasion occurred. It was no coincidence that Cuba treated Angola as a sovereign state (despite many differences) while US politicians had as much respect for Vietnamese as a puppeteer has for his many toys.

No one appreciated the political reality more than South Africans who opened Freedom Park in Pretoria in 2007. Its Wall of Names includes 2103 Cubans who lost their lives in the Angolan war. Cuba is the only foreign country represented on the Wall.

Note. This article is based on the following: information documented in Piero Gleijeses’ Visions of Freedom: Havana, Washington, Pretoria, and the Struggle for Southern Africa, 1976-1991 (2013); interviews by Hedelberto López Blanch which appear in his book Historias Secretas de Médicos Cubanos (2005); interviews by the author reported in his book Cuban Health Care: The Ongoing Revolution (2020); and interviews by Candace Wolf in her unpublished paper, The Zen of Healing (2013). A version of this article appeared in openDemocracy.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Don Fitz ([email protected]) is on the Editorial Board of Green Social Thought. He was the 2016 candidate of the Missouri Green Party for Governor. His book on Cuban Health Care: The Ongoing Revolution has been available since June 2020 and has citations for all quotations in this article.