Remains of Two of Guatemala’s Death Squad Diary Victims Found in Mass Grave

Forensic Anthropology Foundation of Guatemala identifies them through DNA

National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 363

Posted – November 22, 2011

For more information contact:

Kate Doyle – 646/670-8841

[email protected]

English/Español

Washington, D.C., November 22, 2011 – The bodies of two men whose disappearance in 1984 was recorded in the notorious Guatemalan “death squad diary” have been located on a former military base outside the capital and positively identified through DNA testing, according to the Forensic Anthropology Foundation of Guatemala, which announced its findings in a press conference this morning.

The remains belong to Amancio Samuel Villatoro and Sergio Saúl Linares Morales, both captured by security forces in separate incidents and never seen by their families again. Nothing about their fates was known until 1999, when the National Security Archive publicly released the death squad diary, a military logbook created in the mid-1980s to record the abduction, secret detention and deaths of scores of people, Villatoro and Linares among them. In their entries, the document contains a coded reference to their executions. Today, 27 years after their disappearance and 12 years after the publication of the logbook, that information has been confirmed.

“It is an astonishing development in a case that has come to symbolize the impunity and injustice that persist in Guatemala 15 years after its bloody civil conflict ended,” commented Kate Doyle, National Security Archive Senior Analyst. Among the 200,000 civilians killed during the war, there were an estimated 40,000 victims of forced disappearance – men, women and children seized in the cities and conflictive zones by state security or paramilitary forces, interrogated, tortured and secretly executed, their bodies dumped in remote sites or buried in mass graves. Few of the remains of the disappeared have ever been found and only three cases have led to prosecutions resulting in the conviction of former military or police officers.

When security forces kidnapped Villatoro and Linares in Guatemala City in 1984, the army’s scorched earth operations that slaughtered tens of thousands of unarmed civilians in the country’s Mayan regions were coming to an end. The military regime of General Oscar Humberto Mejía Víctores, who seized power in August 1983 in a coup against Gen. Efraín Ríos Montt, sought to dismantle guerrilla networks through a campaign of selective repression targeting suspected subversives in the capital and other urban areas.

The death squad diary is a chilling artifact of the techniques of political terror used by Mejía Víctores during that era. It details the kidnapping of 183 people and uses coded language to record the execution of 93 of them. In order to identify and annihilate insurgent leaders and their alleged collaborators, the military and National Police used surveillance, wiretapping, abduction, interrogation and torture to extract information from prisoners about their colleagues, friends and family members. The military logbook was created precisely to report and classify that information so that security forces could then move against additional targets.

Sergio Linares was one of its victims. On February 23, 1984, as he left his offices in downtown Guatemala City, he was seized by two armed men in civilian clothing and forced into a white paneled van. Later that evening, a group of heavily armed men broke into the house where Linares lived with his mother, wife and 5-year-old daughter. They ransacked the home, taking various possessions and papers, and beat his 68-year-old mother.[1] As a result of the raid and the disappearance of her husband, Linares’s wife Sandra – who was pregnant with their second child – fled their home with their daughter.

At the time of his disappearance, the 33-years-old Linares worked for the National Institute for Municipal Promotion (Instituto Nacional de Fomento Municipal-INFOM) and taught in the engineering department at the University of San Carlos. He became politically active in high school and then more militant when he was a university student in the 1970s. In the military logbook, he is identified as a member of the leadership of the Partido Guatemalteco de Trabajadores (PGT), the Guatemalan Communist Party.

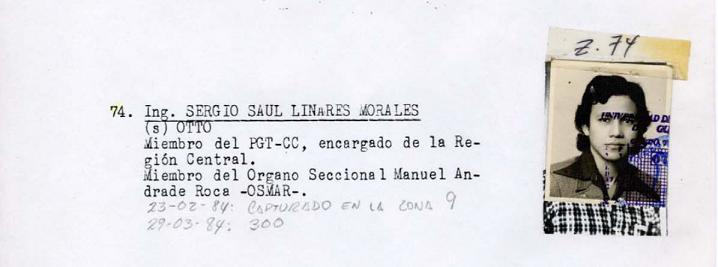

Saúl Linares is entry number 74 in the Death Squad Diary. His remains were locatedin a mass grave in Comalapa, Chimaltenango during an exhumation conducted by FAFG (Guatemalan Forensic Anthropology Foundation). Photo is an excerpt from the Death Squad Diary document, the National Security Archive

Saúl Linares is entry number 74 in the Death Squad Diary. His remains were locatedin a mass grave in Comalapa, Chimaltenango during an exhumation conducted by FAFG (Guatemalan Forensic Anthropology Foundation). Photo is an excerpt from the Death Squad Diary document, the National Security Archive

Linares appears in the logbook as Number 74. His capture came as a result of information provided by another detainee, Julio Cesar Pereira Vásquez, Number 73 in the logbook. Periera was abducted the day before Linares and after being tortured with beatings and electric shock agreed to inform on his companions in the PGT. According to Pereira’s own testimony, given before the Guatemalan press after the National Security Archive made the logbook public, he pointed Linares out to his captors as Sergio left INFOM’s offices and then watched as they seized him.[2]

The death squad diary contains Linares’s university ID photo taped over a second picture. It is not known whether the photos were used to visually identify and track targets or as proof of their abduction. Hand-written below the typed entry describing Linares’s political affiliations are two dates: the date of his capture, and of his death, coded as “300,” on March 29, 1984.

Amancio Samuel Villatoro is entry number 55 in the Death Squad Diary. His remains were located in a mass grave in Comalapa, Chimaltenango during an exhumation conducted by FAFG (Guatemalan Forensic Anthropology Foundation). Photo is an excerpt from the Death Squad Diary document, the National Security Archive

Amancio Samuel Villatoro is entry number 55 in the Death Squad Diary. His remains were located in a mass grave in Comalapa, Chimaltenango during an exhumation conducted by FAFG (Guatemalan Forensic Anthropology Foundation). Photo is an excerpt from the Death Squad Diary document, the National Security Archive

Amancio Samuel Villatoro is Number 55 in the logbook. According to his entry, he was a member of the Revolutionary Armed Forces (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias-FAR) and coordinator of the National Workers Central (Central Nacional de Trabjadores-CNT), a labor federation founded in 1968 that helped organize workers into some of the most important labor unions in the country. The logbook indicates that he was captured on January 30, 1984, in the old center of Guatemala City and held for almost two months until his execution (“300”).

Villatoro’s family members have supplied details of his life in interviews with the “Peace Archives” of Guatemala, an institution founded by President Alvaro Colom’s government to gather testimony and documentation about the civil conflict. One of Villatoro’s four living children, labor activist Néstor Villatoro, said his father was born on December 11, 1937, into humble circumstances in Huehuetenango, and emigrated to the capital for his studies. He married María del Rosario Bran and began a family, while founding and becoming secretary general of the labor union of workers at the Adam’s chewing gum company.

His widow, María del Rosario, recalled the day of her husband’s disappearance. “Amancio left for a union meeting and never returned.. When I went to wait for him at the bus stop, a white panel truck drew up and eight men emerged. That day they assaulted our home, they forced us onto the floor, they tied us all up and they took things from the house, including our money. They left us with nothing.”[3]

Amancio Villatoro’s case is unusual among the victims recorded in the death squad diary because he was glimpsed alive after his kidnapping. Another individual who appears in the logbook, Alvaro René Sosa Ramos (Number 87), was also captured in early 1984 but managed to escape and tell his tale to human rights groups. For two days after his abduction on March 11, Sosa Ramos was held and tortured in a clandestine detention site somewhere in Guatemala City. During his brief imprisonment he saw other prisoners who had been badly tortured, including Villatoro – suffering, but alive. According to the death squad diary, Villatoro was killed some two weeks later, on March 29.

Throughout the years since the disappearance of their loved ones, the families of Sergio Linares and Amancio Villatoro tried repeatedly to obtain information about their fates, to no avail. Government authorities refused to acknowledge anything about the men, their detention, and whether or not they were dead or alive. Testifying before the Inter-American Commission for Human Rights in 2007, Mirtala Linares Morales, sister to Sergio, recalled meeting the de facto chief of state Gen. Mejía Víctores to ask for help in determining where her brother was imprisoned. “He wouldn’t tell us anything; he claimed they hadn’t captured [Sergio], that he knew nothing of his whereabouts – and that maybe my brother had gone as an illegal alien to the United States! That was how he answered us.”[4] Villatoro’s widow, María del Rosario, wanted most of all to find Amancio’s body: “We hope there will be justice one day and that at least we will be able to learn where his remains are to give him a dignified Christian burial.”[5]

The Forensic Anthropology Foundation of Guatemala (FAFG) first unearthed the remains of the two men on September 7, 2003, in an exhumation at the site of a former military base in Comalapa, in the department of Chimaltenango, about an hour and a half northwest of Guatemala City. In a press conference held this morning, FAFG’s director Fredy Peccerelli explained that the skeletons belonging to the men were found lying together. Both had characteristics that set them apart from other remains located at the site. In contrast to the majority indigenous victims buried there, the bodies of the men exhibited dental work in their teeth, and were dressed in middle class, urban attire uncommon in the site (Villatoro’s body had a pair of name-brand Levi’s blue jeans, for example).

Surrounded by the family members of the two men, Peccerelli noted that it took FAFG until today to positively identify the bodies using DNA technology to match the victims with their relatives. He pointed out that the struggle for justice in Guatemala has taken decades but with the discovery of the bodies linked to the death squad diary, “This is only the beginning” of the search for truth about what happened to the disappeared. FAFG will now send its report on the exhumation to the Guatemalan Attorney General’s office for legal action.

It is likely that Villatoro and Linares were brought to Comalapa after their captures for further interrogation. Comalapa and Chimaltenango in general was an intensely conflictive zone starting in the late 1970s when the EGP began operating there and the department became a target of the counterinsurgency strategy of the regime of Gen. Romeo Lucas García. The military base was infamous as source of intimidation and violence. The report of the Historical Clarification Commission (Comisión para el Esclarecimiento Histórico-CEH) contains accounts from residents of Comalapa of the military and dreaded Judicial Police trolling the city for kidnap victims, in cars or pick-ups with polarized windows.

Comalapa also became famous in that era as a dumping ground for the bodies of disappeared activists. In March 1980 the cadavers of student activist Liliana Negreros and some two dozen others were found in a ravine on the outskirts of Comalapa.[6] The U.S. embassy called the discovery “ominous” and suggested that the extreme right was responsible. CIA sources indicated that President Lucas García’s “display of outrage” over the gravesite was for “public consumption only. Highest levels of the Guatemala government through the National Police hierarchy are fully aware of the background of the burial site. .[It] was a place where the National Police Detective Corps disposed of its victims after interrogations.”[7]

One of the Lucas García’s first counterinsurgency forces, called Iximché, targeted Chimaltenango beginning in 1981. So many of Comalapa’s mayors and other municipal leaders were assassinated that a February 1981 U.S. Embassy cable described a “reign of terror,” including political murders, by security forces and says it was becoming “a ghost town.”[8] The CEH took testimonies that described army massacres in and around the town in September 1981 (60 people), November 1981 (one massacre of 12 people, mostly children; in the other the army captured, tortured and executed 14 people, burned houses and slaughtered domestic animals), and January 1982 (36 people). In July 1982 there was a massacre by the insurgent Guatemalan Army of the Poor (Ejercito Guatemalteco de los Pobres-EGP) as punishment for the deaths of two guerrilla combatants, in which 40 people were murdered.

The Forensic Anthropology Foundation’s exhumations on the former army base in Comalapa began in August 2003 at the request of CONAVIGUA, the National Coordinator of Widows of Guatemala (Coordinador Nacional de Viudas de Guatemala), which had compiled a list of 250 names of residents of Comalapa who went missing during the war. Since then, FAFG has uncovered some 220 skeletal remains at the site, many of them showing signs of torture.[9] Even before the discovery of the bodies of Amancio Villatoro and Sergio Linares, Comalapa’s use as a clandestine burial ground for victims of state terror was known to have included people from outside the municipality. In 2004 the Latinamerica Press reported that the identification of corpses found there was more difficult than usual, because many of them were the remains of people from regions as far away as Huehuetenango or Quiché.[10]

The extraordinary work of the FAFG team is all the more important because there is a collective human rights case based on the disappearances of the death squad diary currently pending in the Inter-American system. Filed in 2005 by the Myrna Mack Foundation of Guatemala and involving the family members of 26 of the victims in the logbook, it was remanded to the court by the Inter-American Commission for Human Rights on February 18, 2011, and is scheduled to be heard some time in 2012.

The National Security Archive has worked closely with the Myrna Mack Foundation, lawyers at the Berkeley International Human Rights Law Clinic, and the Guatemalan families to build the case. In particular, the Archive provided expert testimony to authenticate the death squad diary as the product of a secretive military intelligence unit called Archivos (“archives”). The Archivos was an operational section of an agency known as the Presidential General Staff, which served to gather and analyze intelligence for the chief of state. Declassified U.S. documents, archives of the Guatemalan National Police, and other sources identify the Archivos as critical to the urban counter-subversion campaign waged by the Mejía Víctores regime. It was the Archivos that created the death squad diary and oversaw the forced disappearances chronicled in it.

The National Security Archive is now preparing a report to be submitted to the Inter-American Court next year. In it, we will argue that the Guatemalan state is obligated by Article 13 of the Inter-American Convention on Human Rights to respect the “right to truth” of the families and surviving victims of the crimes documented in the death squad diary and must provide unrestricted access to military archives pertaining to those crimes. Although the Historical Archives of the National Police – discovered accidently by human rights investigators in 2005 and since preserved, digitalized and opened to the public – include many hundreds of records related to the disappearances in the logbook, the Guatemalan army has yet to turn over a single document connected to those crimes. The records of the Archivos, the Directorate of Intelligence (D-2), the Center of Joint Operations (Centro de Operaciones Conjuntas-COC), and other military entities that ran the urban counterinsurgency operations in the mid-1980s must be released.

The exhumation of long-secret archives, combined with the exhumation of the mass graves that remain hidden around the country, will represent a critical step toward justice and the rule of law for the families of Sergio Linares, Amancio Villatoro, and the remaining 181 victims of the death squad diary.

Notes

[1] CEH report, vol. VI, “Caso ilustrativo No. 48: Desapariciones forzadas de Edgar Fernando García, Sergio Saúl Linares Morales y Rubén Amilcar Farfán. Fundación del Grupo de Apoyo Mutuo (GAM),” 145-53

[2] Prensa Libre, Miguel Ángel Albizuras, “Julio César Pereira habla de su secuestro,” 13 August 1999, page unknown

[3] Dirección de los Archivos de la Paz, La Autenticidad del Diario Militar, a la luz de los documentos históricos de la Policía Nacional, 131-36

[4] See: http://www.oas.org/es/cidh/audiencias/Hearings.aspx?Lang=en&Session=13 (Caso 12.590, “José Miguel Gudiel Álvarez and Others (Diario Militar) v. Guatemala,” Part one; Mirtala’s testimony begins at 53:00 minutes)

[5] Dirección de los Archivos de la Paz, idem, 135

[6] Paul Kobrak, Organizing and Repression: In the University of San Carlos, Guatemala, 1944 to 1996. Washington, DC: American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1999, 66-67; CEH report, vol. VI, 175

[7] U.S. Embassy Guatemala, Violence Surges in March, 3/25/80; Central Intelligence Agency press statements, [Clandestine Mass Grave near Comalapa], c. 4/80

[8] U.S. Embassy Guatemala, ‘Reign of Terror’ in Comalapa, Chimaltenango Department, 2/11/1981

[9] FAFG Website, consulted 21 November 2011. http://www.fafg.org/paginas/exdestacamentos.htm

[10] Latinamerica Press, Eduardo García, “Digging up the Truth in Guatemala,” 6 March 2004.

http://www.thefreelibrary.com/DIGGING+UP+THE+TRUTH+IN+GUATEMALA.-a0115356778

DOCUMENTS

Document 1

March 25, 1980

“Violence Surges in March”

U.S. Embassy, Guatemala, limited official use cable

(GU00636)

This U.S. Embassy cable reports on the discovery of a clandestine mass grave in Comalapa and lists acts of political violence during March 1980. The grave was found to contain 26 decayed bodies that “show physical signs of ‘death squad’ type executions.”

The cable also notes difficulty of the Guatemalan government’s attempts to dispel impression of official involvement in recent violence. President Lucas García’s administration released a press statement attributing the crimes to “clandestine gangs and extremists.”

Document 2

c. March 30, 1980

“[Handwritten “Demarche” on Death Squads and Comalapa Clandestine Grave]”

Department of State, Classification Unknown, Aide-Memoire

(GU00638)

The demarche states that the USG is “disturbed by the drastic increase in political killings and disappearances of both the democratic and extreme left over the past month.” The USG also expresses shock in response to “the discovery of a mass clandestine grave near Comalapa where victims bore physical signs of death squad executions.” The demarche goes on to say that the USG believes that individuals from “the GOG have been and are involved in these death squad killings.”

The demarche recognizes that “while an investigation of the Comalapa discovery is in progress; such investigations under taken in the past have never resulted in the arrest and trial of those responsible.”

The USG threatens the continuance of approving shipments and aid to the GOG if the GOG does not take “immediate steps to safeguard the basic rights of individuals irrespective of their political persuasion.”

Document 3

c. April 1980

“[Clandestine Mass Grave near Comalapa]”

Central Intelligence Agency, secret cable

(GU00640)

This secret Central Intelligence Agency cable writes that President Lucas García’s publically displayed outrage in response to the discovery of the clandestine mass grave in Comalapa “is only for public consumption.” The cable goes on to assert that it is apparent that the Guatemalan government and National police are fully aware of the background of the grave site.

The cable explains that the burial site in Comalapa was accidentally discovered in March of 1980 and was used as a place to dispose victims after the National Police completed interrogations of the victims. The site is reported to have “upwards of 26 persons who fall into common criminal class (delinquents) and not radical leftists.” The cable also notes that as of March 22, 1980, only two sets of remains have been identified, one of whom was allegedly involved in “criminal activities.”

Document 4

c. February 11, 1981

“‘Reign of Terror’ in Comalapa, Chimaltenango Department”

United States Embassy, Guatemala, confidential memorandum of conversation

(GU00687)

This U.S. Embassy cable describes reports of political terror and murder in Comalapa, Chimaltenango by three villagers and says Comalapa is “becoming something of a ghost town.” The three women “informants” explained of the abduction and murder of many of their community members. The women insist that there is no guerilla activity in the Comalapa area.

When the women were asked if they had any concrete evidence of Army involvement in the killings, the women gave two examples: A case where a person was taken off a bus by people dressed in guerilla uniforms, but several passengers noticed the uniformed people were wearing boots with known military characteristics. Also, at the Army checkpoint at the entrance of the town, soldiers check personal documents against a list of names they carry around.

Additionally, the women agree that “there is no set modus operandi in the killings.”

Document 5

c. February 1983

“[The Archivo and Government-Sponsored Violence]”

Central Intelligence Agency, secret cable

(GU00897)

This cable describes operations by Archivo personnel including authorization to “apprehend, hold, interrogate, and dispose of suspected guerrillas as they saw fit.” It also notes that Ambassador Chapin is “firmly convinced” that increased “suspect right-wing violence” is actually ordered by Guatemalan government.

The cable notes President Efraín Ríos Montt’s anger at the time of his nephew’s kidnapping, and the murder of a police detective and municipal inspector, and the uncovering of a coup plot against him. The cable reports that “Ríos Montt said that the increase in threats to his government and other subversive activities was a result of his government’s lenient policy toward the application of justice.”

Document 6

February 2, 1984

Recent Kidnappings: Signs Point to Government Security Forces

Department of State, confidential cable

(GU00995)

The U.S. Embassy in Guatemala reports the circumstances surrounding two recent abductions in Guatemala City, suggesting that both appear to have been the work of government security forces. The document describes in detail how one of the victims, Sergio Vinicio Samoyoa Morales (death squad diary entry number 60), was abducted from a hospital by ten armed men just before he was scheduled to undergo surgery for bullet wounds suffered earlier that day. In his analysis, U.S. Ambassador Frederic Chapin notes that “these new shocking abductions indicate that the [Guatemalan] security forces will strike whenever there is a target of importance.” Chapin proposes that the U.S. can either choose to overlook these kinds of atrocities and “emphasize the strategic concept” or “pursue a higher moral path,” but should not continue to alternate between these two positions.

Document 7

February 23, 1984

Guatemala: Political Violence Up

U.S. Department of State, secret intelligence analysis

(GU01000)

On the same day that Sergio Saúl Linares Morales was disappeared, the State Department produces an intelligence report on the recent spike in political assassinations and disappearances. The intelligence report describes several notable cases of victims in the “new wave of violence,” over the past several weeks, and provides key information on police coordination with military intelligence in government kidnappings. It mentions the recent abduction and release of a labor leader and confirms that “he had been kidnapped by the National Police, who have traditionally considered labor activists to be communists.” It states that the detective corps (the DIT) of the National Police has traditionally been involved in “extra-legal” activities, working alongside the Army’s presidential intelligence unit, the Archivos.

Document 8

March 28, 1986

Guatemala’s Disappeared: 1977-86

Department of State, Bureau of Inter-American Affairs, secret report

(GU01078)

This Department of State report from 1986 provides details on the evolution of the use of forced disappearance by security forces over the decade prior, and how this tactic became institutionalized under the Mejía Víctores regime. “In the cities, out of frustration from the judiciary’s unwillingness to convict and sentence insurgents, and convinced that the kidnapping of suspected insurgents and their relatives would lead to a quick destruction of the guerilla urban networks, the security forces began to systematically kidnap anyone suspected of insurgent connections.” The documents estimates there were 183 reported cases of government kidnapping the first month of the Mejía government, and an average of 137 abductions a month through the end of 1984. Part of the modus operandi of government kidnapping involved interrogating victims at military bases, police stations, or government safe houses, where information about alleged connections with insurgents was “extracted through torture.”

The document concludes that the U.S. embassy and the State Department have failed in the past to adequately grasp the magnitude of Guatemala’s problem of government kidnapping.