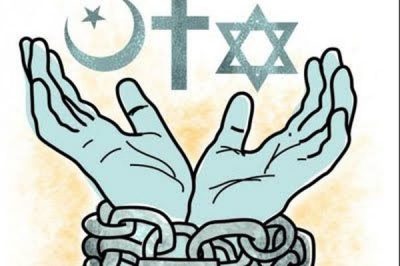

Religion and Geopolitical Strife Helped Create the World Crisis; Spirituality Shows the Way Out

The world is in a depth of crisis that extends well beyond the more obvious outbreaks of geopolitical strife.

Regardless of who, if anyone, is a “good guy” or a “bad guy,” science and technology have allowed collective humanity to develop weapons of mass destruction sufficient to destroy not just homo sapiens, but all life on Earth. Pollution and environmental degradation from industrial, military, and technological uses, including ubiquitous electronic and/or chemical contamination of air, water, and soil, have resulted in a level of peril difficult to diagnose and seemingly impossible to regulate.

We are also seeing a telling correlation between the soaring human population and an epic die-off of non-human species. One result is a documented decline of species at the bottom of the food chain: pollinating insects on land and plankton in the oceans. Already we are seeing a decline in bird populations that feed on the vanishing insects.

As the food chain collapse works its way up to the level of human food supplies, mass starvation could result. We are already seeing adverse effects through lower food quality, as high-glycemic products containing empty calories replace more nutritious and natural foods. A probable result is an explosion of inflammation-caused illnesses like diabetes, cancer, heart disease, and Alzheimer’s.

The spectacle of nations and alliances fighting over supremacy on our radically endangered planet shows humanity’s insane short-sightedness, even as communication and transportation technology have brought people from faraway places closer together. Politically, the destruction is being wrought under a paradigm of nationalism and imperialism that reflects underlying ideologies of competition/predation vs. cooperation/compassion.

“Get what you can while there’s still time,” seems to be the ruling age-old mantra.

All is not lost, perhaps, as sizeable numbers of people are seeking truth through the spirit, which conceivably could also result in a greater sense of personal responsibility and long-term improvement of external conditions. But the immediate danger remains. Can anything bring us out of it short of global catastrophe?

What about the organized religions? The number of people who declare themselves “spiritual but not religious” testify that the two are not the same. Where then is hope for the future to be sought, and how does that hope play out in social, economic, and political life within and among nations?

I have written on these themes since retiring as a federal government analyst in 2007 and publishing my book Challenger Revealed: An Insider’s Account of How the Reagan Administration Caused the Greatest Tragedy of the Space Age. I believed then, and do now, that the Challenger disaster was a microcosm of our era: incredibly complex technology blowing up in our faces and taking human life, mainly due to failures arising from our dishonesty and hubris.

Today’s crisis has a profound ethical dimension: what is right and wrong in our approach to life, how did we get into the present mess, and what we can do now, at the 11th hour, to solve our dilemmas? Inevitably, these questions invoke theology: the study of the divine.

Is there a God? How does He/She/It factor into the problems we face? Can we pray for help or are we stuck with the necessity of solving problems on our own? Are human beings ultimately immortal in spirit, or are we even moral, spending as much time as we do fighting each other over who is right and wrong and over things?

In presenting the following thoughts I want to acknowledge at the outset that I am speaking mainly of life in the West: largely the Americas and Europe (along perhaps with Australia and New Zealand), which is the portion of the world shaped historically by Christianity.

I limit myself in part because of the constraints of time and space. Also, I do not have the direct personal experience needed to comment similarly on life in the Islamic world or those nations formed historically by followers of the Eastern religions.

Nevertheless, the same questions may apply to those parts of the world as well. Let the reader be the judge.

Also, at the outset, I wish to offer the reader an apology. I am neither a scholar nor a specialist, nor someone with any unique knowledge or wisdom. I am an ordinary man, a retired analyst with the U.S. federal government, and an occasional commentator on world events.

But I like to write, and I like to think about “the big issues.” I believe that the urgency of the times requires us to speak up, despite our limitations.

I am grateful to the Global Research website for carrying my material over the last decade. The internet gives may of us a voice who otherwise would have been ignored or suppressed by the powers that control the corporate media.

So, if the thoughts expressed in this essay are of any interest to you, that’s fine. If not, that’s okay too.

The article is long, so relax and take your time. Comments are welcome at the email address appearing at the end.

Lets Start with the American “Evangelicals”

We are talking about “big issues” indeed. Here in the U.S., we are accustomed to the notion of “separation of church and state,” where matters of faith are not supposed to influence public discourse. We are expected to get by through manmade laws, social customs, discussion and compromise, representative democracy, and our innate sense of right and wrong.

You now may be laughing. How is any of this helping today? How much of these things, and their effectiveness, is self-delusion or wishful thinking? Maybe all of it?

Where does religion then fit in? It’s a fact that despite the separation of church and state, the laws of the U.S. and most other nations are religion-based and may be found, for instance, in the Ten Commandments—at least portions of those Commandments that contain prohibitions on murder, stealing, bearing false witness, and adultery, plus an admonition for fair play implied by the prohibition on coveting what belongs to our neighbor.

Like it or not, our laws are rooted in the Judeo-Christian tradition, even though portions of our society, including many corporations, politicians, and intelligence agencies—not just common criminals—appear to consider themselves exempt.

But in both the U.S. and other nations, religious establishments—some ancient but others newly minted—struggle to find relevance. Still, at least in the U.S., public figures cite religious beliefs or predilections to gain support or justify decisions. Beneath the surface, however, is a tremendous spiritual ferment that affects all of society.

Onlookers generally agree that the election of Donald Trump as president of the U.S. would have been unthinkable without the votes and vocal support of white “evangelical” Christians, especially in the South and Midwest. The role of the evangelicals as a political force dates from President Richard Nixon’s 1968 “Southern Strategy,” when the Republicans brought about a shift of the “Solid South” away from the Democrats by playing on white resentment of President Lyndon Johnson’s civil rights reforms.

Image below is from Politico

Now, as the Trump administration attempts to navigate “Russiagate” and keep the Republican Party afloat with the 2018 midterm elections approaching, the president’s strongest source of cheerleading comes from the so-called “Christian Right,” via such figures as former Arkansas governor Mike Hukabee, who broadcasts on the Trinity Broadcasting Network, and standby Pat Robertson of the Christian Broadcasting Network. Also instrumental, among many others, is the support of Jerry Falwell, Jr., who succeeded his father as the head of the immensely influential Liberty University in Lynchburg, VA.

Observers underestimate the emotional force that drives these allegiances. How strongly did Hillary Clinton’s calling-out of Trump’s “deplorables” in the 2016 election backfire?

The politicians who rely on evangelical support have an array of hot-button social issues at their disposal to arouse anger and fear and get out the vote, including abortion, crime among racial minorities, same-sex marriages, and “entitlements,” including the numbers of people on welfare, food, stamps, and Medicaid.

Underlying much of the resentment is good-old-fashioned racism. Many of the more politically visible evangelicals are angry white people. Some of the anger even extends to social programs largely paid for by individual lifetime earnings, such as Medicare and Social Security.

The evangelicals, being good Republicans, are among those who oppose government “interference” in social and economic life, including limitations on assault weapons. Yet they support the biggest “welfare” program of all—the military/industrial/intelligence complex with its millions of employees and multi-trillion dollar budget.

A potent alliance has also taken shape between the evangelicals and the nation of Israel. The evangelicals are heavily influenced by the ideas of “Dispensationalism,” which is a system of theology that began in Great Britain early in the 19th century and takes as literal the supposed prophecies in the Biblical Book of Revelation pertaining to a time of great tribulation, culminating in a final battle between good and evil preceding the Second Coming.

The return of the Jews to Israel in modern times is viewed as an essential stage, with war in the Middle East culminating in the battle of Armageddon. But then comes the “Rapture”(!) when the Chosen People of God will be rewarded for their faith and fortitude.

Some find traces of modern-day Zionism in the political agitation carried out over a century ago by the British Dispensationalists who first developed it into a system under someone named John Nelson Darby (1800-1882). This agitation, along with centuries-old persecution of the Jews in Europe, often led by the Catholic Church, led to the Balfour Declaration of 1917 and the creation of the state of Israel in Palestine after World War II.

The leaders of modern Israel have consciously allied themselves with the American evangelicals, including financial support for institutions like Liberty University, paid trips to the Holy Land, etc. Dispensationalism has also made inroads into the Catholic Church, as well as the chaplain services at the military academies and the regular armed forces.

But is Dispensationalism the truth? Its claims have been debunked by many scholars, including Elaine Pagels of Princeton University.

In her book Revelations: Visions, Prophecy, and Politics in the Book of Revelation, Pagels makes clear that the Biblical text does not refer to a supposed “end of the world” that may happen any time, much less in the 20th-21st centuries, but rather images, themes, and ideas growing out of the destruction of Israel through the Jewish-Roman wars of the 1st and 2nd centuries.

For followers of the author of The Book of Revelation, John of Patmos (not John, the disciple “whom Jesus loved” and supposed author of the Fourth Gospel), the “Whore of Babylon” was pagan Rome and the state religion based on emperor-worship. But by the 4th century, when Christianity had become the official religion of the Roman Empire under Emperor Constantine, this “Whore” became whatever “heresy” happened to be current among competing groups of Christians.

Many of those labeled heretics were so-called because they did not accept, or had no need, for the increasingly powerful hierarchy of bishops, priests, and deacons ruling over the dioceses the imperial rulers had parceled out.

In other words, Church officialdom didn’t have a clue of what John of Patmos might have meant when he wrote The Book of Revelation three centuries earlier. Rather the violent imagery of God smashing up the enemy of the hour proved a handy device of power politics for the ruling structure.

“God is on our side” has a long pedigree.

This organizational imperative assured that, under Constantine and his successors, the strange document John of Patmos wrote made it into the official Bible. Ever since, Christians have been wondering what The Book of Revelation is really about, with some gaining encouragement to periodically give away all they own and stand on hilltops awaiting an end that does not come.

One of the latest was Harold Camping, “the California preacher who used his evangelical radio ministry and thousands of billboards to broadcast the end of the world and then gave up public prophecy when his date-specific doomsdays did not come to pass.”

Camping died in 2013 at age 92. “His independent Christian media empire spent millions of dollars—some of it from donations made by followers who quit their jobs and sold all their possessions—to spread the word on more than 5,000 billboards and 20 RVs plastered with the Judgment Day message.”

A few centuries ago, the great Protestant reformer Martin Luther said the Bible should not even contain The Book of Revelation, as “there is no Christ in it.” (Elaine Pagels, Revelations: Visions, Prophecy, and Politics in the Book of Revelation, Viking Penguin, 2012, p.3) Yet today, John of Patmos’s narrative, with the Four Horsemen, the Apocalypse, Armageddon, and the rest, still provides immense emotional backing for U.S. policy of endless war in the Middle East.

Spirituality in the West Today

With Catholics also, the social issues of abortion, etc., have brought about a shift toward the right, even though Catholics, back when many were newly-immigrated from such nations as Ireland, Italy, and Poland, traditionally formed the backbone of big-city Democratic Party politics. The growing conservatism of Catholics has manifested through the ongoing reaction against the reforms of Vatican II, reforms that began in the early 1960s but have largely ground to a halt today.

This conservatism has led many Catholics to oppose Pope Francis, who has had the nerve to suggest that divorced people might still be allowed at Mass or that Catholics should stop breeding “like rabbits.” Some even regard Francis as an “anti-pope,” due to his attitudes of inclusivity.

The 1960s not only saw Vatican II, along with a tremendously popular surge among Catholics in individual religious experience through the Charismatic Renewal, but liberalizing tendencies among both Protestants and Jews that played important roles in the agitation against the Vietnam War, and in the civil rights and antipoverty movements. But the upsurge of the 1960s was not carried on by the next generation, so, along with the aging population from that era, has tended to fade away.

For many people who no longer found sufficient meaning in the Christian churches or Jewish synagogues, Eastern spirituality also appeared on the scene in a big way in the 1950s and 60s. Today, Eastern practices such as yoga, meditation, and traditional Chinese medicine have replaced or supplemented church participation for millions of people.

Some Christian churches have taken to practices like “meditation with mantra,” a kind of spiritual exercise borrowed from Hinduism/Buddhism, but also found among such early Christians as the Desert Fathers.

Unlike the evangelicals, practitioners involved in Eastern teachings tend to support progressive causes or have dropped out of politics altogether. Also influential, especially among Middle Eastern immigrants or many African-Americans, are the teachings of Islam.

Another spiritual movement with major social impact has been Alcoholics Anonymous and related 12-Step recovery programs. AA is based on principles of spiritual practice drawn largely from Christianity but often much more intensely personal and experiential than what is found in the churches.

AA provides a home for many people who are, or consider themselves to be, outcasts. AA can be found worldwide, including among Native American populations, and specifically eschews any political bias. Members may still have strong political opinions, of course.

Speaking of Native Americans, a powerful revival of native spiritual traditions is underway throughout the Americas, sometimes, but not always, in combination with Christianity. This includes some Amazon shamans who venerate Our Lady of Guadalupe along with Jesus and the saints.

Many people find spiritual value in their activities of daily life—family, profession, team or individual sports, interpersonal relationships, or contact with nature. This may or may not be found in combination with institutional religion or may satisfy a person for a while but intensify into something deeper or more personal as time passes. Of course such activity may be mixed up with motives of greed, fear, or obsession, but so may formal religious practice.

There are also people who find a deeper spiritual sense by grappling with personal or psychological problems, including the huge numbers affected by childhood traumas and abuse, by PTSD, or by issues arising through health crises, addictions, financial stress, or victimization. Often these issues are impervious to generalized religious guidance and require intense one-on-one-work with a professional therapist. Such therapy may include a spiritual dimension.

For many people, one-on-one or group therapy doesn’t work or is not affordable. Many rely on the vast array of psychoactive drugs for relief. For some, such medication is the only thing that makes normal life even possible.

Even atheism and agnosticism may attempt to offer a quasi-spiritual solution to the problems that beset everyone as part of human life. The philosophy of existentialism speaks to people in their loneliness and lack of guidance in a world where everyday values of achievement and acquisition offer little comfort.

Much of modern literature, art, and music is based on existential themes. Carson McCullers’ book The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter captured the mood. So did J.D. Salinger’s A Catcher in the Rye. Existentialism has penetrated theology through such works as Paul Tillich’s The Courage to Be.

Of course there is often a thin line between existentialism and a nihilism that may lead to self-destruction.

With these diverse movements underway, all of which can be experienced in combination with others, and taking into account the pervasive materialism of consumer culture, attendance at mainstream churches has plummeted, with many closing their doors or barely keeping afloat.

Some churches attempt to remain relevant by offering meeting space to community groups or by doing volunteer work among the poor, the sick and dying, or prison populations. Others try to survive as bastions of tradition, though often with declining congregations.

Others rely on emotionalism or spreading the fear of damnation to attract, engage, or keep followers. Often churches or individual ministers broaden their appeal by TV, radio, or on-line broadcasts.

But many people are sleepwalking through life without being particularly interested in anything other than the ups and downs of daily existence. For them, such a life may be sufficient, although they are easily manipulated by propaganda, advertising slogans, political electioneering, mindless media fare, etc. The sleepwalking masses may in fact be the most dangerous component of society.

The Dark Side

Spirituality definitely has a dark side. We already discussed some of that with our reflections on the link between Dispensationalism and endless war.

There are many other inhabitants of the shadowy world of borderline cults—the lairs of gurus, secret societies, occultists, covens, esoteric groups, channelers, “the UFO community,” on-line “masters,” various spiritual predators, etc. Fortunes are often made by these practitioners through their appeal to people’s fascination with the mysterious and the unknown, thereby taking advantage of our genuine need for companionship and reliable guidance.

Cheats and swindlers abound in these fields, including many, it is said, who are themselves deceived by demonic entities that inhabit the twilight spheres. The internet is an apt vehicle for all this.

Then there is the world of alcohol, drugs, gambling, prostitution, pornography, loan sharking, money laundering and other deviant pastimes intended to captivate souls. There does in fact appear to be a powerful Satanic presence on planet Earth that utilizes these things for its purposes.

One of these purposes may be to waylay or even destroy souls that are seeking to escape the downward pull of planetary life through their spiritual striving. All who are serious about their spirituality recognize the power of such allurement, as well as the temptations of fame, power, and greed.

The Satanic forces are aided by their human minions who make billions of dollars off their fellow beings by corrupting and destroying them. These minions pay a heavy price, of course, for the benefits received.

It would be nonsense to claim that such deviance does not have a political role. Hitler and the Nazis were occultists. It has been acknowledged by the CIA Office of Inspector General that the spy agency is involved in international drug dealing. Profits are widely believed to fuel the “black budget” used to overthrow foreign governments, etc.

One of the kingpins who was key in financing Donald Trump’s successful 2016 presidential bid, thereby contributing to the upright goals of the Christian evangelicals (!), was a Las Vegas casino magnate, Sheldon Adelson. Among the most important early financiers of Israel was the American organized crime figure, Meyer Lansky.

This is not to say, of course, that religious institutions that appear on the surface to be legitimate are not corrupted as well. Sometimes such corruption breaks the surface, as with the scandal involving widespread pederasty among the Catholic priesthood. When asked about corruption in the Papal Curia, Pope Francis reportedly said:

“And, yes…it is difficult. In the Curia, there are also holy people, really, there are holy people. But there also is a stream of corruption, there is that as well, it is true….The ‘gay lobby’ is mentioned, and it is true, it is there….We need to see what we can do…”

But the existence of evil in the world does not necessarily support the perspective presented by the Book of Revelation that has been used over millenniums to justify attacks by the orthodox on dissenters. It was the Christian churches that exploited the “good vs. evil” paradigm it inherited from the Roman Empire, with those who are “good” going to “heaven” and the “evil” going to “hell.”

As Elaine Pagels describes in her book previously mentioned, this attitude actually was formed in a very short time during the formation of what became the Catholic Church in the 4th century C.E., when Christianity became the Roman Empire’s official religion. (Ibid, p.133ff) As noted earlier, the Book of Revelation then became the club the Church used to bludgeon people who fell outside the structure of diocesan religion headed by bishops, priests, and deacons. For them, ordination assured a salary, state approval, security, and status.

Gradually, the clergy became a celibate cadre of professionals who held the “Keys to the Kingdom.” Scripture, often ambiguous in meaning, was used—possibly even forged—to prop up the system.

The good vs. evil mythology has continued ever since to support wars, crusades, genocides, inquisitions, pogroms, witchcraft trials, “clashes of civilization,” etc.

The same mentality continues today as the U.S. fights much of the world to uphold its self-image—and privileges—as the “exceptional nation.” It’s part of the same self-centered delusion. Meanwhile, the real sources of evil slip through the net of discernment.

The brand of organized Christianity that developed through history as the handmaiden of the imperial state was based on an “us vs. them” psychology. The “us” would be saved; the “them” condemned.

It’s really the psychology of the wolf-pack—the destruction by the strong of the weak. Social Darwinism has played into this mentality.

The Protestant Reformation was intended at first to correct this twist by allowing every believer to be a “priest” in studying and applying the teachings of Jesus. But the Protestants were never able to complete their revolution. They were taken over by the rise and dominance of the European nation-state.

Protestants too fell in line with the power of the imperial establishment, eventually becoming the evangelicals of today. Jesus, the mediator of love for all, cannot be blamed for this.

Of course the European nation-state gave way to the might of the U.S. through two world wars and countless smaller ones. We might note the strange resemblance between the power and privileges of the Christian clergy, at least up until recent times, to today’s military hierarchy. Both are afforded an adoration verging on worship.

Both are intensely conservative. Both also have as their objective control—of human populations and of resources.

Both aim to preserve the wealth and power of societal elites. Both give lip service to religious values.

Both have depended for their livelihood on demonization of an enemy—heretics for the churchmen, “terrorists” and Russians for those in uniform today. It’s even more uncanny that both derive at least some of their justification from The Book of Revelation, with today’s evangelicals bridging the gap of almost two thousand years.

The fact that both are outdated is shown by their total inability to bring humanity back from today’s brink of self-annihilation. Something new, different, unique, and positive is needed.

Listening to the Germans

While the foregoing provides enough material about the present status of spirituality in the U.S. to make the necessary points, the same also applies to what may be found in Europe, as well as Australia and New Zealand. There is one big difference in that the clergy of mainstream churches in some countries are paid a salary by the government. This may keep a church in operation, even though it may have little active congregation.

Not that such support is inappropriate. Many European churches, for instance, are very old and integral parts of a nation’s cultural heritage. They can and should be preserved, including their traditional liturgy for those who want and need it. Nevertheless, in countries with a state-supported church, taxpayers can usually opt out by declaring that they do not have a religious affiliation.

As in the U.S., most churches in Europe today are searching for a mission. In both England and Ireland, we see a search for the spirituality of the past going back to Celtic or Druid days. Europe, including Russia, is also host to a huge diversity of spiritual paths, including those from indigenous Eastern religions. Also within Russia can be found a profound revival of the Orthodox Church.

But Europe has something the U.S. and the other English-speaking nations lack; namely, a deep familiarity with the cultural accomplishments of the Germans, including those of the German-speaking Austrians and Swiss.

We are familiar with parts of this tradition. We appreciate the heritage of the great German composers, especially Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven. In philosophy we have a passing acquaintance with Kant and Hegel. We have heard of Goethe. We know that modern psychology was pioneered by German-speaking practitioners like Freud and Jung.

We are handicapped by an anti-German prejudice left over from the two world wars. Another handicap is American ethnocentrism that prevents us from learning foreign languages. This is caused by a combination of factors: national pride, the size and relative isolation of the U.S. from other parts of the world, and plain laziness.

But to truly plumb the depths of what the German world has to say to us today, we must humble ourselves and dig deeper. If we do so, we sooner or later will end up at the doorstep of Karl Barth. Standing near him is the martyr of World War II, Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

Karl Barth: 20th Century Prophet

First, Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906-1945), who died too young, executed by the Nazis even as the Americans were fighting their way into Germany at the end of World War II. Bonhoeffer was hanged for his association with the army plots to assassinate Hitler. Much of his relatively slender body of work is available in English translation, including the poignantly-titled The Cost of Discipleship.

When Bonhoeffer came to the U.S. as a young man to study for a couple of semesters at the Union Theological Seminary in New York, he found the lectures boring because they mainly aimed at preparing students for holding jobs as church pastors.

This led to shallowness and complacency in the teaching. Nor could Bonhoeffer abide the fundamentalism and racism he found when traveling to the American South.

So he ended up spending much of his time at the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem presided over by Rev. Adam Clayton Powell, Sr. He said the blacks were the only ones he found in America with enthusiastic devotion, and for the rest of his short life he continued to play and sing their music—he was a pianist—among his students back in Germany.

But it is Karl Barth (1886-1968) to which I wish to devote most of the rest of this essay. Barth’s is a name many have heard spoken, but few know what he actually said and how that is relevant today. He became world-famous after World War II, making the cover of Time in 1962, when he traveled to lecture to large audiences in the U.S.

But time was not kind to Barth. He was not easy to understand, though contemporaries compared him to such figures as St. Augustine, St. Thomas of Aquinas, Martin Luther, and John Calvin. His writings were studied by Catholics and Protestants alike, as a small library of commentaries appeared.

But today the English translations of most of his books are not even in print. Copies of his magnum opus, the fourteen-volume Church Dogmatics (a forbidding name!) are almost impossible to locate, and even so, may cost hundreds of dollars for a used edition.

The German Protestant theologians were tough-minded thinkers. They started the “historical Jesus” movement and rejected notions they thought were borrowed from Greek mythology like the Virgin Birth. Many rejected infant baptism or argued against a physical resurrection of Jesus’s human body.

Like their forebears Luther and Calvin, Protestants rejected the idea of a celibate clergy, so their clergy married and raised families. The Protestants also viewed monasticism as unnatural and running away from life. Many of them also took seriously Jesus’s affections for the poor and downtrodden.

In his first assignment as a pastor in Safenwil, Switzerland, the young Karl Barth spent so much time helping the workers in his congregation organize a trade union that he was called “Comrade Pastor.” This earned him the ire of local industrialists who thought a clergyman should help the riff-raff happily keep quiet. Later Barth joined the Social Democratic Party.

In December 1911, at the age of 25, Barth published an article in the socialist daily Free Aargau that defined his views of the relationship between social justice and Christianity to which he would adhere for his entire life. The article was explained decades later by his biographer, Eberhard Busch:

“In it, Barth drew a contrast between the church, which for 1800 years had failed to deal with social needs, and Jesus Christ as the partisan of the poor, for whom there had been ‘only one God, in solidarity with society,’ and according to whom one ‘has to be a comrade to be a man at all.’ True socialism was the true Christianity for our time. However, true socialism was not what the socialists were doing but what Jesus was doing. This was also the socialists’ ultimate aim, but only their aim.

“Barth did not say all this in order to win the workers to the church. How could he? ‘Jesus is not the church’; indeed, with its ‘pie in the sky’ attitude towards material needs, the church was opposed to Jesus Christ.

“Barth spoke as he did, rather, because he believed that the Kingdom of God was close to the poor and that Jesus identified himself with them. In this sense, ‘the real significance of the person of Jesus can be summed up in the two words ‘”social movement.”’ Therefore, ‘the spirit which counts before God is the social spirit.’” (Eberhard Busch, Karl Barth: His Life from Letters and Autobiographical Texts, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. 1994, p.70)

At a time when mankind had fallen in love with his own image, following on the Enlightenment and the triumphs of the Industrial Revolution, Karl Barth, of a lineage of Swiss Reformed theologians and growing up in small Swiss city of Basle with its palpable medieval heritage, saw humanity instead as a community of down-to-earth people striving to live by faith, but always susceptible to failings of character and intent.

While some theologians were tearing down the mythology the churches had always attached to the person of Jesus and seeking through liberalism and humanitarianism to find a way to have human goodness without qualification or sacrifice, Barth felt deeply the inability of people to live decent and humble lives without the revelation from God the Father that came through his Son Jesus Christ.

For Barth, the parable of the prodigal son was central to an understanding of how far unredeemed humanity could stray from the true meaning of life. He took seriously the idea that a Christian life began with the baptism of repentance as taught in the pages of the New Testament and saw as its central image the suffering of Jesus on the cross, followed by his death and spiritual resurrection.

Barth’s journey brought him eventually to a theology based on the Word of God as taught in the Bible and given to mankind through grace. His departure from the newfangled and modernistic doctrines that departed from this vision led him to a lifelong work referred to today as “neo-orthodox.”

His teachings were also called “Christocentric,” in that theologians were not called upon to give their own interpretations but to make accessible to contemporary humanity what Jesus was really saying. Notably, he did not include any of the “millennial” teachings based on The Book of Revelation in his ministry.

As indicated in his views on social justice, Barth viewed Jesus as having special care for those broken in life and needful of compassion. At the height of his fame, and upon his mandatory retirement from teaching at age 70, he spent a significant part of his time ministering to men and women in prison.

He didn’t just preach there; he also spent time with individuals in their prison cells, getting to know them, and seeing the light of goodness in their hearts, minds, and souls.

Barth’s attitude saw special meaning in the horror of World War I and the complete destruction of human pride, especially in Europe, by the useless sacrifice of millions of young men in the trenches and on the battlefields of both the Western and Eastern fronts. Following that war, the demoralization of humanity was complete, with a Germany seething in anger at the punitive measures adopted by the Allies at Versailles.

After the war, Barth became known for his book on The Epistle to the Romans. Here was a theologian who actually believed what the Gospels said, without promulgating his own subjective interpretations to suit the church politics of the day.

Barth first published his book on The Epistle to the Romans when he was only 32 years old. It was significant that he found the heart of Jesus’s teaching in the presence of God manifested through the interaction between the Apostle Paul and the early Roman Christian congregation.

Paul wrote the Epistle sometime between 55-58 CE. This was long before a formal church with bishops, priests, deacons, dioceses, and a formally-approved canon of approved scriptures even existed.

Accordingly, Barth was not writing about the churches. In The Epistle to the Romans, he spoke of “the criminal arrogance of religion,” as opposed to “that final apprehension of truth which lies beyond birth and death—the perception, in other words, which proceeds from God outwards.” (Karl Barth, The Epistle to the Romans, Translated from the Sixth Edition by Edwyn C. Hoskyns, Oxford University Press, 1933/1968, p.37)

Barth’s book became a best-seller and radically altered the course of theology in the German-speaking world. He was not attempting to destroy organized religion, but to get it to change.

After a time, he was called to teach at Bonn University in Germany. While there he saw the rise of Nazism first-hand and was appalled. The elevation of the German state and later of Hitler as Führer to semi-divine status was, to Barth, in direct contradiction to the First Commandment: “I am the Lord thy God. Thou shalt have no other gods before me.” (Exodus 20: 1-3)

When the German churches fell in line behind a Nazi-ordered dictate to make religion a branch of the almighty German Reich, Barth was instrumental in organizing a counter-movement called the Confessional Church. In a statement written by Barth, Jesus Christ was affirmed as the sole head of the German Protestant religious establishment.

In 1935, after Barth was dismissed from his post in Bonn by the Nazi regime, he was accompanied on a train out of the country by the Gestapo. Barth was not the first, nor the last, to be persecuted by government for “whistleblowing.” He returned to Basle, where he taught at the university for over two decades.

It was then he wrote Church Dogmatics as guidance and instruction to the Protestant ministry, along with many shorter books, sermons, addresses to meetings and conventions, and an enormous private correspondence.Church Dogmatics eventually reached 14 volumes, though Barth viewed it as unfinished.

Barth knew everyone of spiritual stature in Europe and welcomed students and visitors from around the world, including the U.S., India, and Japan. He was also read and studied by Catholic scholars and was invited as an observer to Vatican II, though he declined to attend for health reasons.

But he was not always popular, especially with the press, with both church liberals and conservatives, and with many political authorities. After World War II he encouraged the churches to reach out and minister to the defeated Germans, including ex-Nazis, and he refused to take a stand against communism, sometimes traveling behind the Iron Curtain and helping ministers who were in trouble with state authorities.

Barth took a public position firmly against atomic weapons, as well as any preparations for atomic war. He considered even the existence of these weapons a sin against God and urged their abandonment by Western governments, even unilaterally.

He opposed any hint of rearmament in Germany as well as any movement toward militarization in Switzerland. But he was not a doctrinaire pacifist. He believed in the right of self-defense and carried a rifle during World War II as part of the home reserve.

He also opposed the literalism of Biblical fundamentalists and the vehemence of evangelism, even though the German Lutherans also called themselves “evangelical.” Barth had some harsh words for Billy Graham, who came to preach in Switzerland in 1960. He wrote:

“He acted like a madman, and what he presented was certainly not the gospel. It was the gospel at gunpoint. He preached the law, not a message to make one happy. He wanted to terrify people. Threats—they always make an impression. People would much rather be terrified than be pleased. The more one heats up hell for them, the more they come running.”

The gospel, wrote Barth, is not an “article for sale.…We must leave the good God freedom to do his own work.” (Eberhard Busch, op.cit., p.446)

Barth addressed the idea of “sin” differently from most. This concept is perhaps the chief stumbling block for people faced with the stance of most Christian churches in the West.

People have been berated, preached at, made to feel guilty, threatened with damnation, and even burned at the stake for their “sins.” Jesus’s saying to “let he who is without sin cast the first stone” is thus ignored.

Catholics and Protestants alike have “cast the first stone,” with many people leaving the churches as a result, while viewing church authorities, often concealing their own peccadilloes, as hypocrites. This led Barth to conclude that many churches are not Christian at all. Some churches he saw as “dead,” while others as anti-Christian.

Condemnation of suffering humanity as an attitude was foreign to Barth. He chose instead to view sin as error, often, if not always, resulting from ignorance, immaturity, or illness. He equated sin with “stupidity.”

For Barth the three primary “sins” that separate us from God are “arrogance, sloth, and lies.” He wrote, however, that “Christian ethics cannot itself give commands, but only guidance on the right way to put the question, ‘What shall I do?’, so as to hear God’s answer readily and openly.” (Ibid, p.443)

In other words, Barth did not abandon or water down the central teachings of Jesus, but he focused on Christ as a person, “appointed” as the Son of God, who gave up his earthly life in order to show people that there were higher values than physical existence and that once it ended here on Earth, life still went on. Jesus was living proof of the immortality of not just the soul, but of the human person.

In our time, this insight has been strongly affirmed by the testimony of the many people undergoing near-death experiences who returned with messages about the continuation of life on the “other side,” and about the love emanating from the spiritual beings they have met, including, at times, a figure sometimes referred to as Jesus Christ himself.

If you want to know what Karl Barth was talking about, first read the Gospels carefully, especially the Sermon on the Mount. But I would suggest you read them with joy and gratitude for what has been made available to us as individuals and a community. We can try to see how they might be applied in our daily lives, not as a club to beat up others with.

The goal, as Barth wrote about at length in Church Dogmatics, is reconciliation between man and God. God always takes the initiative in this, though man must seek help and then cooperate when it comes. It was Jesus on the cross that made—and makes today—reconciliation possible.

We can now return to the opening theme of the crisis in human affairs that threatens annihilation but may also mark the end of an era and the start of the next. Karl Barth was a prophet of the next stage of human development.

But he said, and this is important, that Christianity “is not a religion.” By that he seemed to be referring to all the paraphernalia of religion, including services, structures, organizations, and the blasphemous worship of the state. Barth said there “may be a religious West, but there is not a Christian West: there is only Western man confronted with Jesus Christ.” (Ibid, p.468)

So for Barth, what life is about is the resurrection of the individual. “…The experience of salvation is what happened on Golgotha.” (Ibid, p.447)

What makes this possible while we are alive on Earth is a spiritual energy that can reach us within our own consciousness. This energy Barth associated with the Holy Spirit. He said that a person “can have the experience of God’s spirit come on him and over him.” (Ibid, p.456)

Decline of Religion

Meanwhile, church membership in Europe has plummeted far more than in the U.S. Barth was aware this would happen. He even foresaw a time when followers of Jesus would meet in small groups. This decline includes Germany, in spite of the fact that Germany’s ruling coalition under Chancellor Angela Merkel is headed by the party that calls itself the Christian Democratic Union.

The traditional strongholds of the CDU are in Catholic regions of Germany to the west and south, including, in particular, Bavaria. There, an independent Christian Social Union exists parallel to the national CDU.

But even in Germany, the prevailing post-World War II cultural affinity to a resurgent traditional Christianity is fading as society changes. A 2013 article entitled “Germany’s Great Church Selloff,” in Spiegel Online said, “Dwindling church attendance and dire financial straits are forcing the Catholic and Protestant Churches in Germany to sell off church buildings en masse. Some are demolished, while others are turned into restaurants or indoor rock climbing centers.

My own sense is that people today are so distracted by the spectacle and busyness of life they have lost acquaintance with the world of the heart, soul, and spirit that lies within A major factor that numbs consciousness is the obsession with media fare, whether it be on a computer (iPad, iPhone, laptop, tablet, Kindle, etc.), in front of a TV, or at a movie or a loud concert, or some other dream activity or event.

It is as though a spell has been cast on humanity, as in the fairy tale “Sleeping Beauty.” The sleep is a fitful one, of course. More often than not, it is a nightmare. Each of us inhabits his or her own nightmare, though they often overlap or coincide.

No one knows what will happen to the world and humanity over the decades to come. Of course we hope that sin, a.k.a. “stupidity,” will not play itself out to its seemingly logical conclusion of a worldwide nuclear war.

To see leaders of the U.S. and some other nations flirting with such a possibility is appalling. To see religious leaders falling in behind such political figures can only be viewed with astonishment—and disgust.

A greater betrayal of real spirituality cannot be imagined. What are they thinking?

What must be changed is the fundamental idea that “goodness”—defined, of course, by the power structure—can only be brought about by force through the might of the totalitarian state acting as God’s agent on Earth. This idea is destroying humanity and the planet.

Spirituality for the Future: The Teachings of Bô Yin Râ

Let us hope that out of the darkness a new day may dawn. I believe this could happen, especially for those who care to investigate the possibilities voiced by another German who began speaking in the early 20th century.

Few people outside of Germany have heard of the spiritual master Bô Yin Râ, who was a little older than Karl Barth. He was born near Frankfurt, Germany, in 1876, and passed away in Massagno/Lugano, Switzerland, in 1943.

His birth name was Joseph Anton Schneiderfranken. Bô Yin Râ was a name he received from his spiritual mentor whom he discusses in his work, The Book of Dialogues.

By profession, Schneiderfranken was a talented landscape painter. As a spiritual guide, he had thousands of students in the German-speaking world. Some readers may have heard his name in association with Eckhart Tolle, who was inspired by the writings of Bô Yin Râ while a young man.

To conclude this essay, I will quote verbatim from a review on Amazon.com of Bô Yin Râ’s book, Bô Yin Râ: An Introduction to His Works. The review is by someone named “Richard Montana”:

“The man who was perhaps the most important spiritual master in the West during the 20th century is almost unknown to English-speaking readers. He was a German artist and author whose spiritual name was Bô Yin Râ. (Birth name Joseph Anton Schneiderfranken, 1876-1943.) “For the last 20 years of his life he resided with his family in Switzerland. During his lifetime he published a 32-volume compendium of spiritual books that he termedHortus Conclusus, meaning, in his words, a ‘self-protecting enclosed garden.’

“In the latter part of the 19th century, starting with the Theosophical Movement, rumors had begun to circulate in the West that somewhere in the heart of Asia was a high spiritual center that was the source and overseer of all planetary spirituality. Bô Yin Râ confirms the existence of such a center and identifies himself as its authorized representative in bringing true information about its teachings to light.

“In 1976 the Kober Press of Berkeley, CA, began to publish translations in English of books in the Hortus Conclusus cycle. The result is an astonishing unfoldment of deep and authentic spiritual guidance that, in my experience, has no parallel, including the publications in English from other schools and centers that claim to possess hidden knowledge.

“What is unique about Bô Yin Râ is the clarity and force of his expositions that not only explain spiritual ideas but also show clearly how they may be put into practice in life-changing ways. The volume Bô Yin Râ: An Introduction to His Works is an invaluable companion to the much larger body of work, with the added benefit of containing commentaries on his life and work by the master himself.

“Among the many topics covered are the awakening of an individual’s spiritual senses, making contact with helpers from the spiritual world, and how he himself acquired his spiritual experience and decided to make his teachings public, despite his natural inclination to remain silent.

“Bô Yin Râ also includes in his body of work detailed information about the life and mission of Jesus of Nazareth, whom he describes as an authorized Luminary from the planetary center. While the life and teachings of Jesus (known as Jeshua during his lifetime) were utilized to construct the religion we know as Christianity, deeper meaning on individual spiritual transformation is available.

“For instance, Volume 11 of Hortus Conclusus, entitled The Wisdom of St. John, has chapters on ‘The Authentic Teaching’ and related topics that will prove highly practical for seekers who wish to delve beyond the explanations found in religious creeds. I am grateful to the Kober Press for their work in opening Bô Yin Râ’s work to English-speaking readers and am looking forward to more volumes appearing in the months and years ahead.”

I would only add to this review Bô Yin Râ’s indications that, if a person is satisfied with the simple faith of his or her inherited religion, there is no need to read his books. For the rest of us, including the “lost,” the case may be different. These are the ones he was trying to help.

Today, we in the West are indeed “lost.” But in his book On Prayer, Bô Yin Râ explains the meaning of Jesus’s advice: “Seek, and ye shall find.” This is advice well worth investigating.

*

Richard C. Cook is a retired federal government analyst. He is author of “Challenger Revealed: How the Reagan Administration Caused the Greatest Tragedy of the Space Age,” along with “We Hold These Truths: The Hope of Monetary Reform,” and numerous print and internet articles on public policy issues. Mr. Cook may be reached at [email protected]. He is a frequent contributor to Global Research.