Reflections on Prison National Strike Against Slave Labour

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

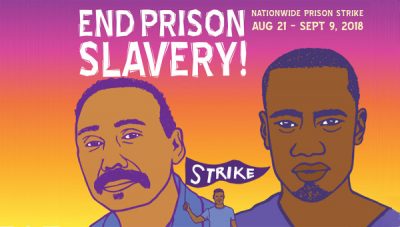

Prisoners in many states in the U.S. began a coordinated National Strike on August 21, the anniversary of the killing of Black Panther member and prison activist George Jackson by guards in an escape attempt, in 1971, at San Quentin prison in the San Francisco Bay Area. In the context of the times, a mass radicalization led by Blacks and youth, the incident became a cause celebre.

The strike was set to end on September 9, the anniversary of the great prison uprising at the Attica prison in New York, also in 1971. The rebellion was crushed in blood, in a massive attack ordered by Governor Nelson Rockefeller, billionaire scion of the oil industry family. This too deepened the mass radicalization by exposing the horrors of U.S. prisons.

The central demand of the current actions – which range from work stoppages, hunger strikes and sit-downs to boycotts of prison stores – is an end to prison slave labour.

Most Americans and people around the world do not know that slavery is allowed in prisons by the U.S. Constitution. The Thirteenth Amendment, which ratified the abolition of chattel slavery of African Americans won in the Second American Revolution (Civil War), contained a fatal flaw. It allowed slavery of people convicted of a crime, i.e. prisoners, although not of ownership of them (chattel slavery).

Jim Crow in the South

Almost immediately, states, especially in the former Confederacy, began passing vagrancy laws to round up ex-slaves and sell their labour. This was curtailed in the period of Radical Reconstruction, but emerged full-blown in the counter-revolution to the Civil War that established Jim Crow in the South. White rule created a huge economic sector based upon unfree Black labour, as in the prison chain gangs at institutions as the notorious Parchman Farm in Mississippi, as well as in contract labour, where private capitalist firms worked Black prisoners into the grave.

Prison slave labour was also implemented in the rest of the country, although not as violently as in the Jim Crow South.

While the Black movement in the 1960s and ‘70s overthrew the Jim Crow system, prison slave labour has continued throughout the country.

The current action by prisoners must be seen as a part of the labour movement, as a movement of part of the working class, whose employment as slaves lowers the wages and conditions of the whole working class.

While white prisoners are also employed as slaves in work inside the prisons as well as in contract work for outside firms, 60 per cent of prisoners are African American or Latino, with 38 per cent Blacks. Given the whole history of unfree Black labour from chattel slavery up to the present, it isn’t surprising that reports reaching support organizations on the outside say that Blacks have taken the lead in these multiracial actions.

Much work by prisoners in many institutions isn’t paid for at all, direct slavery. In other prisons, the slavery is barely covered up by pitiful ‘wages’.

Here are what some prisoners report:

Anthony Forest: “Because I know how to strip floors, wax them, take the gum up off floor, I started doing that. At 16 cents an hour.”

Darryl Aikens: “I started out as a line server, serving food for breakfast and dinner. Then I became a dishwasher and maintenance in the kitchen. It paid 13 cents an hour. I worked and made $20 a month, and they [prison authorities] took 55 per cent of that for restitution [for food etc.]”

Cole Dorsey: “It’s kind of like a modern-day plantation situation, specifically targeting poor people, and most especially, the most marginalized communities, black and brown…”

For some prisoners, the ‘pay’ is more, even up to $2 an hour, but some of that is taken back for ‘restitution’.

The Demands

There are nine other demands prisoners are raising in addition to an end to slave labour, centering on prison conditions and prisoner rights. One of these is the right to vote. Only two states, Vermont and Maine allow prisoners to vote. In the remaining 48 they cannot. Given that there are some 2.8 million prisoners, that’s a large number who are disenfranchised. This is in contrast to Canada and 14 European countries where prisoners can vote and 16 more where some can vote.

Four states – Iowa, Florida, Kentucky and Virginia – permanently deny felons the vote for the rest of their lives after being released from prison. Six others do the same for some felons. Others deny parolees the franchise.

Given that the majority of prisoners are African American or Latinos, the denial of their right to vote is part and parcel of racist laws in a majority of states progressively whittling down voting rights for racial minorities won in the radicalization of The Sixties.

Part of the background is the sheer size of the prison population in the USA. The statistics are well known. With five per cent of the world’s population, the U.S. has twenty-five per cent of the world’s prisoners. This is the result of a deliberate policy of the ruling capitalist class, carried out by both parties of big business. From 1970 to 2005, the prison population rose 700 per cent, and remains high today.

A major tool the government has used is the phony War on Drugs. While begun by Republicans, it was sharply intensified under the Democratic administration of Bill Clinton in the 1990s, which saw an acceleration of the rate of arrests and convictions for drug offenses, including for simple possession and other non-violent ‘crimes’.

The Clintons were part of the fear of “Black crime” whipped up in the 1990s. Hillary Clinton coined the phrase “super predators” – young Black men devoid of humanity, preying on white people. Under her husband, the president, a law was passed restricting the rights of prisoners to seek relief from their mistreatment through the courts. One of the demands in the current strike is to repeal that law.

In the 2016 election, candidate Hillary Clinton defended the “super predators” phrase, as did her husband while campaigning for her, against vocal Black Lives Matter protestors.

Given the highly disproportionate number of Blacks who were swept up, a key element of all this is “The New Jim Crow,” a new form of the national oppression of African Americans, a new caste system, explained by Michelle Alexander in her book of that title.

This goes well beyond the time Blacks are locked up. Once released, the onus of being an ex-felon coupled with institutionalized racism means that it is difficult for Black ex-prisoners to find meaningful employment, and other results of their being imprisoned. So there is a large number of Blacks who are still caught up in the system long after they have done their time.

It is difficult to obtain the full information about the strike, as the authorities just deny that anything is happening in in their prisons, or punish leaders in ways that make it hard to communicate with the outside.

Amani Sawari, an African American woman, is a spokesperson for Jailhouse Lawyers Speak, a network of prisoners who have studied the law while inside, helping to organize the strike. She is now on the outside, and reports on the retaliation against the strikers. Two leaders she mentions are Jason Walker and Comrade Malik, both in solitary confinement.

“Comrade Malik hasn’t been allowed to take showers. They are hunger-striking. Jason Walker hasn’t been allowed to have toilet paper, towels or have access to taking a shower or having clean clothes, in retaliation to his organizing of the strike in Texas.”

She explains that Comrade Malik was sent into solitary confinement, itself an internationally recognized form of torture, in a preemptive move on August 15. “He’s in a concrete cell that’s over 100 degrees Fahrenheit in Texas…. He’s only escorted out in handcuffs. He’s not allowed to have easy communications with the outside.”

Jason Walker wrote an article about the conditions in Texas prisons. “After that article was written, he was moved to solitary confinement. But even in groups, like in South Carolina, prisoners in McCormick [prison] have been having daily strip searches done on them since August 20, the day before the strike began.

“Also, David Easley and James Ward, they are in Ohio [state prison], Toledo’s correctional facility, are not allowed to have contact with the outside. They’re also in solitary confinement.

“So we can see that retaliation is happening against individual organizers in the beginning. And now we’re seeing when inmates are standing up and choosing to strike, they are moved to solitary to try to keep prisoners from joining. But this is spreading the fire. Prisoners know that this is a climate where they can actually stand up and feel supported. There have been solidarity marches and rallies in at least 21 cities across the country.”

These brave men and women taking action in the face of being retaliated against not only deserve our support. We must begin to educate the labour movement and all workers that prisoners are part of the working class, and it is in the interests of all workers to come to their defense.

*

[Quotations are abridged from interviews on Democracy Now. The historical part on the Thirteenth Amendment and its results is paraphrased, with additions by me, from an op-ed in the New York Times by Erik Loomis, history professor at Rhode Island University – BS.]