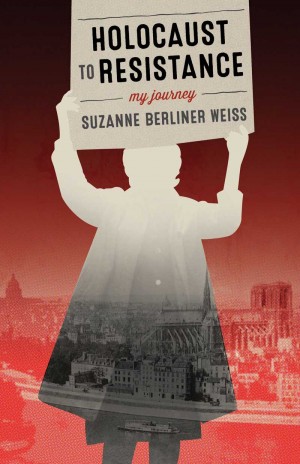

Holocaust to Resistance, My Journey

An excerpt from Holocaust to Resistance: My Journey by Suzanne Berliner Weiss (pp. 45-47). Weiss’s book, released this month by Fernwood Publishers, tells of her eight decades of engagement with the movement for social justice. Her book launch will take place Friday, October 18, at 7 p.m., at Friends House, 60 Lowther Ave. (St. George Station), Toronto.

***

When I arrived from war-scarred France (1950), I thought the United States, my new home, was a land of liberty, freedom, love, and comfort. I entered grammar school and began to learn its true nature. It tore my heart.

Louis Weiss, my adoptive father, was proud to have sung as a young man in the opera chorus in a performance of Boris Godunov in Moscow, Russia.

Russia! At school, the word was spoken with hate and fear. Often, my parents invited their “progressive” friends over, and I got to listen to their chatter. They didn’t mention Russia but spoke of the Soviet Union with respect. When I asked questions, they used guarded terms. “Progressives” were the good people, and as for those who were “against us,” that was everyone else.

My parents covered many books in the apartment with brown paper against the inquisitive eyes of maintenance men, visitors, and housekeepers. On buses and subways there were signs warning “foreigners” to register with the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS). In school, a fellow student warned me, “You’re lucky that you’re from France. Otherwise, we could send you back.” To be perceived as an immigrant was decidedly hazardous, I thought.

At school I heard that “our enemies” were among us – the communists. Mom explained it differently: There was persecution of “progressives.” Some of them were in jail, some in hiding. She confided that before my arrival she and Dad had hidden a couple in their apartment at the request of the Communist Party. “You must be careful to protect me from losing my job,” Mom explained. When she and Dad talked with their friends about world events, it was with hushed voices. “Don’t tell your schoolmates anything about this,” she counselled.

Mom and Dad allowed me to listen in on their discussions of the news, as they focused on the opinions expressed in the radical newsletter I.F. Stone’s Weekly, which they spread out on the table. In 1956, the tone of these discussions changed. A secret speech by Soviet Communist Party leader Nikita Khrushchev, leaked to the daily press, revealed many of the crimes of Joseph Stalin, who had died three years earlier.

This news weighed heavily on my parents, who had been loyal to Stalin. They discussed the situation anxiously with their friends. I recalled how, when Stalin died in 1953, Mom had gazed at his image and said, “What a kind face. He was so good to the people.” I had wondered how you can tell kindness by looking at a face. But now it turned out that much of the anti-Soviet propaganda in the US media, decrying the stifling of civil liberties there, had in fact been true. Jewish doctors and scientists had been murdered. “I must look at things with new eyes,” Dad declared.

I respected his honest response; it created some much-needed common ground for us.

A Wave of Fear and Repression

The atmosphere was different when we visited Aunt Dorothy. There was open discussion in her house. Friends who gathered there were upset and angry about the persecution of progressives and communists orchestrated by Senator Joseph McCarthy. They spoke of people they knew who had lost their jobs. Ben Gold’s furriers’ union was in danger of destruction, they murmured. It was he, Dad told me, who had written Shmulek in France to open the road to my adoption. Aunt Dorothy was unnerved and Mom and Dad were fearful.

When the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) came to Newark, its blows struck the family of Aunt Dorothy. Robert Lowenstein, the teacher of Dorothy’s daughter, Joan, was summoned. He refused to give names of progressive associates and was therefore fired from his job, leaving his family in desperate straits. Dorothy’s husband Hy, angry over the incident, courageously hired Lowenstein to work in his combined pharmacy, soda fountain, and liquor store. I was very happy to hear of Hy’s principled stand.

My Cousin’s Bold Stand

After her high school graduation, Joan went to Antioch College, where she was involved in radical activities. She and her partner at the time attended the World Youth Festival in 1955 in Warsaw, the capital of the Polish People’s Republic. The theme of the festival was For Peace and Friendship – Against the Aggressive Imperialist Pacts.

Much to Dorothy’s dismay, Joan was subpoenaed to appear before the HUAC. Mom and Dad spoke of this with alarm. Joan took the Fifth Amendment’s constitutional safeguard against self-incrimination. For that, she was ordered to surrender her passport, but she refused, and her audacious stand made the media. “I got regular visits from the FBI from then on. But I didn’t let them in my apartment,” she told me. I was proud of Joan’s boldness and strength.

Senator McCarthy’s outrageous anti-communist accusations turned up a large proportion of Jewish people, and it was widely suspected in our circles that he was hunting Jews more than communists. Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, a Jewish couple with a “progressive” background, were hauled into court, tried over a two-year period, and found guilty of giving secrets to the Soviet Union. On Friday evening, June 19, 1953, Mom, Dad, and I were in the car listening to the radio when we heard that the Rosenbergs had been executed in Sing Sing prison. I was stunned. How could this happen in America? “America is for peace, liberty, and justice,” Mr. Berman [my guardian in France until 1950], had told me. Tears flooded my eyes. It was evident that Mom and Dad felt as I did. “Can you believe the government killed them?!” Mom cried.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.