Advice for People Fearful and Under Duress

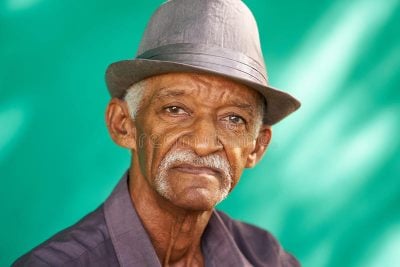

Reconsider High-Risk Granpas and Sanctions-Surviving Immigrants as Untapped Resources

We have a natural impulse to extend protection to the very young and to the old first; we offer sympathy and succor to traumatized refugees too.

That’s reasonable. Our seniors and our children require attention as the most vulnerable; immigrants need support in unfamiliar surroundings.

Professors speaking about historical precedents for the COVID-19 emergency invoke the Great Depression and chaotic hospital scenes from World War II. But, hey: we know about that, and more, first-hand!

Yes. So, why not consider us elders, along with our immigrant citizens as assets at this time of crisis and fear–untapped resources? We have abundant practical advice for people fearful and under duress, counsel based on our past experience.

We may not operate computers as nimbly as the young, but priorities are changing. As the COVID-19 crisis makes apparent, some skills become redundant; you’re unmoored from your once brawny anchors. When you’re really scared and grope for alternatives, turn not to apocalyptic movie scenarios but to what seniors have seen and done before you were born, what immigrants were shy to share. Our histories may offer guidance and solace in today’s disaster. We can tell you about our strategies and you can discover how we managed to cope. We’re here as a result, aren’t we?

If elders didn’t suffer a pandemic, we endured other plagues, and we survived because of habits we devised, here not only because America offered sanctuary and opportunity, but also because we rebuilt our lives resourcefully. Heard of ‘rationing’? –A great, simple strategy. Improvisation too. Both painless habits.

We’re grateful to our energetic daughters and grandsons who happily set up our phone apps and install our Netflix. You’ll Google anything—even if we don’t really need it– from potato peelers to airline bookings, and hearing aids– all delivered to our distant home. (Yes, we succumbed to that pampering.)

Surely now’s the time we can reciprocate with tips we learned from our less indulgent, less fast-paced and frugal past.

We can tell you how to recycle cardboard and plastics, invigorate a stew for a second meal, review the merits of baking soda, trim your hair, repair a car or bicycle tire, forage for wild edible plants, disinfect fresh vegetables, substitute one spice for another, preserve surplus food, stitch a face mask.

To survive we adjusted our social skills too, learned dexterity needed to endure wars’ deprivations.

Separated from loved ones, prayer became more routine; we rationed essentials, prioritized limited resources, reused clothes. We hunkered in underground shelters during a bombing blitz, slept on cold floors, coupled with our husband even with mother-in-law and children just meters away. We used water instead of toilet paper—it works great, left hand only (you can learn). We recycled bath water for cleaning, rewashed cotton diapers and sanitary cloths.

These are a few elders’ memories and tips. We’d welcome a chance to share them, granted you’ll doubtless improve on them too.

Then, we are millions of immigrants, refugees from wars (often of U.S. making) who’ve witnessed waves of attacks. Day-after-day we lost a loved one, often unable to perform the last rites for our dearest ones. We turned to caring for our wounded, dared to shelter underground resistance fighters. We rushed from one place to another, seeking somewhere to hide. We left behind a child, an aged parent, a sick friend. We also devised ways to avoid nagging mothers or garrulous brothers. Families became closer, and humor emerged from shared traumas. We endured more than bombardments; sometimes we were hunted down by government commandos, attacked by desperate citizens or rebel militias.

A more threatening curse imposed on us by outside enemies was embargo. Our Iraqi, Venezuelan, Iranian, Vietnamese, Palestinian and Syrians citizens can tell you about embargo-created deprivations, death and isolation– a battering more deadly and invasive than any physical assault. These are contemporary U.S.-perfected and murderous applications of economic and cultural embargoes, sieges sanctioned and extended by the lofty, noble United Nations. (Iraq’s embargo was endorsed in 1990 by the U.N. Security Council/General Assembly, and adhered to worldwide for 13 years! The Vietnam embargo, imposed by the U.S. after its defeat, extended for two decades.)

Documentation of the sanctions-war on Iraq (imposed in 1990 ended only in 2003!) augmented by US-led military bombardment, is hardy remembered today. (My accounts from Iraq during that period published by U. Press Florida, joined those of the International Action Center and published in the 1990s were reports from the field. Later came a Harvard study based on secondary sources.)

Three warning notes from personal experience in Iraq suffice to suggest the trauma Americans, their European and Australian supporters of that war will themselves confront in their neighborhoods very soon.

The first from my friend, sculptor Mohammed Ghani, on my initial visit to Iraq in 1989. Foremost among the memories he felt compelled to share rose from the just ended Iran-Iraq war. “Every day, passed cars with coffins strapped on top, holding the bodies of our sons (back from the battlefield of Al-Faw). Every day, every day; they drove by: one, two, then another, another”, he moaned.

Hardly a year later came the invasion of Kuwait and the first U.S. Gulf War. Among those I interviewed soon after was journalist Kthaiyer Mirey. Among institutions smashed by American bombings in 1991 was Shamaiya Hospital for psychological diseases. Hospitalized for alcoholism, Mirey managed to escape from the bombed smoldering ruins. Many staff were killed; feckless survivors along with some patients escaped. “The dead and wounded”, Mirey told me, “were abandoned; then the dogs entered the debris to clean up.”

Third, was my own witness of an eternal line of martyrs, their portraits imprinted on banners –Iraqi soldiers who’d fought ISIS (under U.S. occupation during the past decade).

Images of overwhelmed morgues and columns of unaccompanied hearses have reached us from Italyand Spain this week. That will become part of the American landscape.

Young Americans are not yet ready for this; perhaps resourceful elder veterans and refugee victims from U.S. wars abroad can help sustain us. (Then there’s the comfort of our voice.)

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Author-anthropologist BN Aziz has published widely on Nepal and returned from an extended stay there last December. Her journalism articles on Nepal are posted at www.RadioTahrir.org.