Recommendation X: Shell’s Secret Plan for a Cold War Propaganda Unit

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Visit and follow us on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

Declassified files show how British oil giant Shell hatched a secret plan in the 1960s to defend the West’s share of the global energy market, with help from UK propaganda and intelligence agencies.

British oil corporation Shell hatched plans for a secret Cold War propaganda unit, recently declassified documents reveal.

In 1960, Shell commissioned a report into “communist efforts to disrupt the operations of major oil companies” across the developing world, and what private industry should do about it.

The report was authored by Sir George Sinclair, a staunch anti-communist who had spent decades in Britain’s colonial services, and whose brother was the general manager of Shell in Burma.

Between 1960 and 1962, Sinclair used his long-standing links with the Foreign Office to produce the report, receiving “the greatest help from Her Majesty’s Government and from Shell, not only in London but also…in many countries overseas”.

Sinclair drew particularly on the resources and advice of the Information Research Department (IRD), Britain’s covert Cold War propaganda arm. He also collaborated with Britain’s intelligence services.

In his final report, Sinclair warned that communist activities across Asia, Africa, and Latin America had serious “implications for Western oil interests”.

To this end, Sinclair attached a secret appendix to his final report, detailing plans for a private industry-funded propaganda unit designed to defend the West’s share of the global energy market.

The unit would be funded by Britain’s leading oil, banking and pharmaceutical companies, and engage in covert information operations across the developing world in the service of Western private enterprise. Its annual budget would run into the hundreds of thousands of pounds.

The degree to which the proposal for the unit was implemented, and whether the campaign was successful, remains unclear. But the plan throws new light on the Foreign Office’s relationship with big oil during the Cold War, and how covert propaganda operations were seen as a device to maintain Western control over global oil supplies.

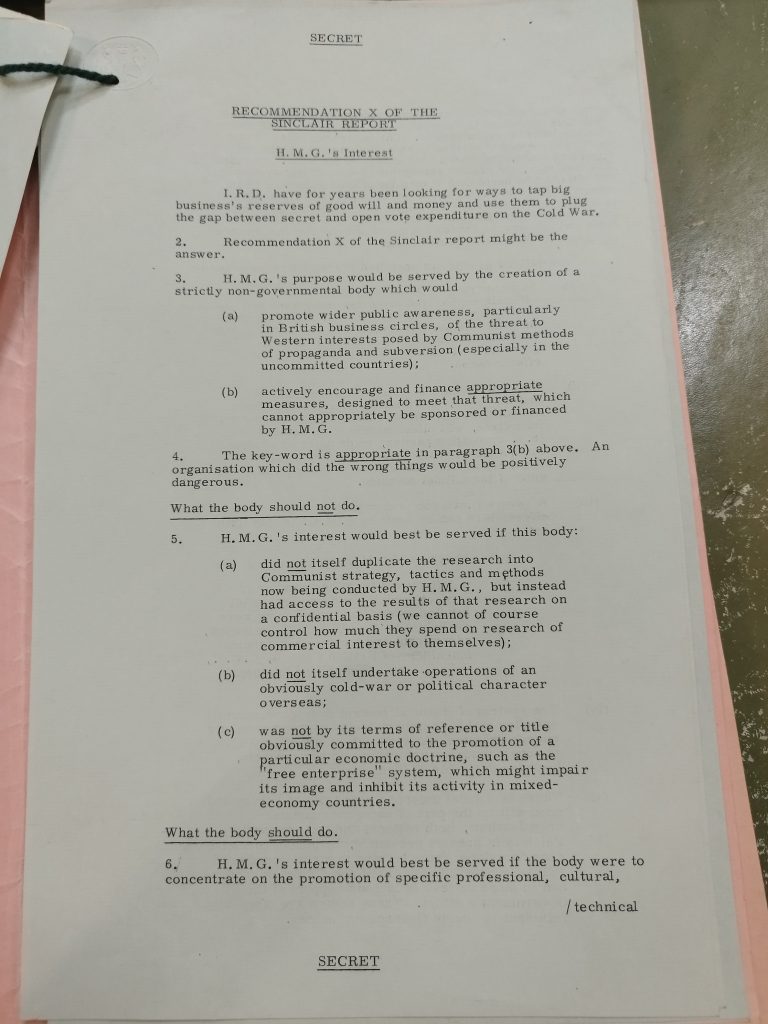

Recommendation X was discussed in secret. (Photo: John McEvoy)

Recommendation X

The secret plan was codenamed “Recommendation X”, and was drawn up “in close association” with IRD chief Donald Hopson, his predecessor Ralph Murray, and Foreign Office official Leslie Glass.

Britain’s intelligence services were also aware of Sinclair’s activities. In October 1960, Sinclair met MI5 chief Roger Hollis for “a discussion about his new job and the extent to which we [MI5] may be able to help him in it”. Details of the meeting were then passed on to “C”, MI6 chief Sir Dick White.

After numerous drafts and redrafts, Recommendation X was finalised on 5 February 1962. The document ran to 52 pages, specifying the requirement for a big business-funded propaganda unit, as well as its functions, structure, staffing, and costs.

There was a “gap to be filled” in the information field, wrote Sinclair, given that “Western free enterprise…has been declared by the Russians as a target to be weakened and destroyed”.

Sinclair thus recommended the unit have “two interdependent divisions”: one “for assessment” of the risks to Western industry, and the other “for projection” of a “favourable image” of Western private enterprise across Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

To this end, Sinclair proposed that the unit use “unattributable material indirectly commissioned through some third party” to project “the basic case for… private enterprise”.

Sinclair also suggested that funds be provided “confidentially” for “non-attributable anti-Communist work in areas of particular financial interest” to Shell and other major Western companies.

This included “visits of influential people to the UK and visits of suitable Western personalities to the key areas overseas”.

In making the case for private enterprise across the developing world by covert means, the unit would mirror tactics used by the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the IRD during the same period.

Indeed, Sinclair recommended using British and US intelligence-linked organisations to use and distribute the unit’s material, such as the Economic League, Interdoc, and the Latin America Information Committee.

The ‘Unit’

Sinclair could not decide on a name for the organisation, and referred to it simply as the “Unit”.

However, he insisted that the “choice of a title for an organisation that has some overt and some covert activities is important”. It was, he said, “often best to select a title that describes the overt activities as accurately as possible and thus provides a convincing cover story for the other work of the organisation and its staff”.

As such, he preferred something along the lines of the “Overseas Industrial Research Unit”.

It would require one director, one deputy director, one chief research economist, three research officers (one for each Latin America, Africa and Asia), one statistics officer, two production officers, an accountant, a registry officer, a librarian, two secretaries, and a messenger. Such staff needed to be “of high calibre” to make “a real impact in the war of ideas”, he wrote.

In the unit’s first year of operation, costs of staff, offices, consultants, and production were estimated to be £134,350, roughly £2m today. By the unit’s third year, costs were projected to rise to £410,170, over £6m today.

Shell would be the primary, but not the sole sponsor of the unit.

To get the organisation off the ground, Sinclair proposed approaching a number of Britain’s leading oil, pharmaceutical, chemical and banking companies such as BP, Unilever, ICI, British-American Tobacco, Barclays, and the Bank of London and South America.

“Once discussion of this project between Shell and HMG had reached a stage which would… justify an approach to other industries”, Sinclair wrote, the managing directors of Shell should approach Unilever and, with Unilever, approach ICI and, with Unilever and ICI, approach the banks, and so on.

“If the free enterprises of the West wish to foster, in the developing countries, a climate of ideas favourable to the survival and expansion of the free enterprise system, they should, in my view, tackle this problem now”, Sinclair emphasised in an earlier draft.

Such a project would be “bound to” meet “nationalist resistance”, he lamented, and therefore the unit should “get local leaders and organisations” to contribute as much as possible.

“This is a pump priming exercise: so is outside aid and technical assistance: both are liable to run up against nationalist feelings, but both are necessary. What is important is that both operations should be carried out as sensitively as possible”, he concluded.