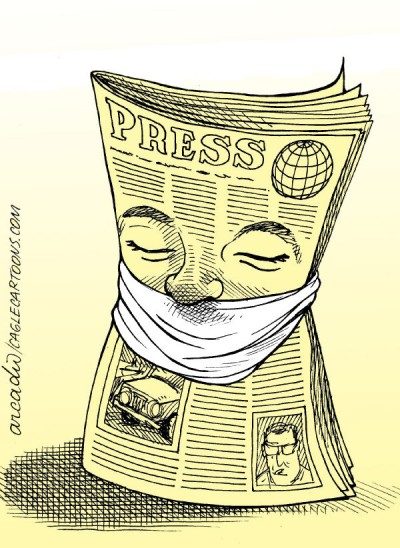

Press Freedom in Britain: Getting Darker

Journalism is under attack across the world - including the UK

Britain leads the way in Europe – but not in a good way. It has a worse record on press freedom than all other European nation states except Italy, trailing others such as Norway, Sweden and the Netherlands.

In the 2018 World Press Freedom Index, an annual report, by Reporters Without Borders (RSF), Britain was judged to have been in 40th place. This compared to Norway and Sweden at the top of the index, with the UK coming in below Trinidad and Tobago and only just ahead of Taiwan. The United States is also trailing, to the dismay of American media organisations, coming in at 45 on the list (with North Korea in bottom place, at 180).

Britain’s ranking, from the World Press Freedom Index 2018

RSF has drawn attention to several issues that may have contributed to Britain’s place in the ranking. It says: “A continued heavy-handed approach towards the press (often in the name of national security) has resulted in the UK keeping its status as one of the worst-ranked Western European countries in the World Press Freedom Index.”

It points, in particular, to online threats against journalists, many of them women, proposed changes to the Official Secrets Act, repeated attempts to impose state-backed press regulation – and a legal action by the law firm, Appleby, against the Guardian and the BBC, for work on the Paradise Papers. The UK is the only place where such proceedings have started in the wake of international revelations over tax avoidance.

The UK’s poor ranking has drawn reactions from freedom of expression organisations.

“It’s depressing that the UK has maintained its recent low ranking in the world press freedom index”, said Jodie Ginsberg, Chief Executive of Index on Censorship, a body campaigning for freedom of expression. She added: “The environment for press freedom is declining globally and we need to see leaders speak out more in its defence. Instead we see the likes of Donald Trump smearing anyone who criticises him as a peddler of ‘fake news’. This does little to promote the central value of press freedom, as a cornerstone of democracy, around the world – and in fact emboldens those in positions of power everywhere to suppress further journalists and journalism.”

So what does this mean for us, as journalists working in the public interest? As Index on Censorship says, about its project to map media freedom, journalists and media workers are confronting relentless pressure simply for doing their job.

A straw poll of journalists in the Bureau itself demonstrates that restrictions on press freedom have impacted on work and reduced our capacity to tell stories that matter, both in the UK and abroad.

My own work has been affected, in the UK and in Iran, where family members live. One of my books, Hear My Cry, on “honour” violence affecting a British-Yemen citizen, has had to be published elsewhere in the EU, as potential publishers here were concerned about the weak safeguards for public interest journalism here under the Defamation Act.

Image on the right: Quarmby family photograph, of the journalist and birth father in Iran in 2007

When I visited family in Iran in 2007, under the Ahmadinejad regime, I travelled to the country on a tourist visa, rather than a journalist visa, as I knew that I could then meet family members and friends without a minder present. As my Iranian birth father, like many other naval officers, had been imprisoned after the Revolution (pictured, but blurred for safety, below) it would have been risky for him to meet me if I was under constant surveillance. When I returned to the UK, I did write and broadcast on my experiences in Iran. But I am aware that it would be problematic to go back now, as the current regime targets journalists – and their families, if they have Iranian connections. I would be putting myself and my Iranian birth family at risk. Iran was ranked at 164 on this year’s press freedom list.

The Bureau itself, with other organisations supporting freedom of expression, currently has a case at the European Court of Human Rights, about which our managing editor, Rachel Oldroyd,has written. The Bureau brought the case in 2014, with the aim of forcing the government to provide adequate protections and safeguards for journalists’ privileged communications. Without these protections, we argued, the government’s actions were a direct threat to a free press and indirectly would have a chilling effect on whistleblowers seeking to expose wrongdoing. In November 2017 the arguments were made in a rare aural hearing at the court, combined with two other cases brought by a group of human rights organisations including Amnesty International, Privacy International and Liberty. The case is currently being considered.

Bureau managing editor Rachel Oldroyd, with Rosa Curling from Leigh Day and counsel Conor McCarthy, of Monckton Chambers, at the ECHR

Jessica Purkiss, one of the Bureau’s foreign affairs reporters, has also faced difficulties. She says:

“While reporting on issues in Palestine I was deported by the Israeli authorities. Israel controls the borders to Palestine so entrance depends on their approval. The security personnel were clear to tell me that I was not being deported for being a journalist but for taking a photo of a Palestinian protest – something that was not illegal to my knowledge – which they had obtained by going through my computer. After a night in a detention cell, I was escorted onto a plane back to the UK and my passport withheld until I landed on British soil. I have been banned from Israel, and therefore from visiting Palestine, for ten years.”

She has also faced problems in Palestine:

“During my time in Palestine I wrote a story about the poor treatment of teenagers arrested by the Palestinian Authority. I received a call from their press office informing me that if I didn’t provide the names and addresses of the children, I could face charges of withholding evidence.”

Israel was ranked at 87 on this year’s list and Palestine at 134.

Meirion Jones, our investigations editor, has also encountered difficulties in his long career in journalism.

Just this week one of the British fraudsters who sold fake bomb detectors to Iraq was given two more years prison time under proceeds of crime legislation because he wouldn’t surrender some of the millions of pounds he made from his crime.

The fraud, which probably cost the lives of 2,000 Iraqis who were blown up after the detectors failed to detect explosives, was uncovered by a team led by the Bureau’s Investigations Editor Meirion Jones when he was at BBC Newsnight (pictured above with a fake detector). But Jones believes a major reason that the fraudsters set up business in the UK was because the libel laws made it so difficult to expose them: “One of the bogus bomb detector makers hired extremely expensive lawyers to threaten to sue us for libel if we said the detectors were fake”, he said.

He also did the original investigation into the paedophile Jimmy Savile (image on the left):

“Savile was protected for years by British libel law and lawyers, including the late George Carman QC. Many in the British press knew or suspected Savile was a paedophile for decades but were too afraid of being sued for millions to tell the truth – we need a US First Amendment style law which guarantees freedom of the press.”

Our Afghan expert, Payenda Sargand, faced an uncomfortable experience in Dubai.

“I was detained for taking the photo of a plain commercial building in Dubai in 2003. The police detained me and confiscated my camera after they spotted me getting ready to take a photo of Emirates Towers [a building complex in Dubai]. I explained to them that I was a journalist and I had not yet even taken a picture of the towers. Their argument was that it was illegal to take pictures of the complex. They took me to a police station and kept me for over eight hours, under a freezing air conditioner. Their behaviour was unprofessional and rude. I have tried to find out more about this ever since. I believe the only reason for my detention was to do with the fact that I am Afghan. It didn’t matter that I was a journalist.”

The United Arab Emirates is 128 on the World Ranking.

Another Bureau journalist, whose experience is anonymised to protect the source, had problems in Vietnam (ranked this year at 175).

“While trying to partner on a sensitive subject I was assigned a press minder. On the one day I tried to report on my own I received an anonymous text message, warning me that the police would be waiting for me if I travelled to meet my source. In fear for my source I cancelled the meeting and managed to get the story another way.”

Most chillingly, of course, is the fact that journalists die every year because of their work in war-zones, unmasking corruption and speaking truth to power, most recently the Cypriot journalist, Daphne Caruana Galizia. Journalism is not a crime – but reading the World Press Freedom Index this year, you would be forgiven for thinking that it is all too often seen as one.

*

Katharine Quarmby has years of experience as a journalist and writer, specialising in investigative and campaigning journalism.