Predators, Warriors and Ravens: the CIA Drones Wage War

The CIA’s use of unmanned aircraft to kill insurgents and militants marks a turning point in the history of war

THE COURTYARD of the Pentagon feels like a cross between an arms fair and a used-car lot on a fine May morning. “Congratulations 1,000,000 Army Unmanned Aircraft System Flight Hours,” says a banner.

With 5,456 US servicemen killed in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the Afghan war going badly, the US military celebrates what it can. Unmanned Aircraft Systems, also known as Unmanned Aircraft Vehicles but referred to as drones, are the military’s most important technological asset. Last year the CIA’s director, Leon Panetta, called the Predator drone programme “the only game in town”.

“We’ve reached a turning point in the history of war, and maybe in humanity,” says Peter Singer, director of defence studies at the Brookings Institution and author of Wired for War , which chronicles the shift to robotic warfare. There were only a handful of drones in the inventory when the US invaded Iraq in 2003, Singer says. “Today there are more than 7,000 airborne drones, and some 12,000 ground-based robots . . . Very soon there will be tens of thousands.”

This week the army chose to advertise its drone revolution by inviting journalists to a press conference celebrating the millionth hour. Col Gregory Gonzalez, project manager for Unmanned Aircraft Systems, tells us drones are equivalent to the use of radar in the second World War, or helicopters in Korea and Vietnam. “They’ve been funding us really well, because they know there’s a bang for the buck,” Col Gonzalez says.

A representative selection of the army’s drones are displayed in a lane under the trees. There’s a Shadow, equipped with an Israeli-made camera, used mainly for surveillance, but also for some targeting, and the diminutive Raven, a battlefield surveillance drone that is launched by hand.

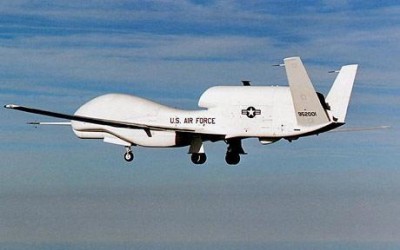

The only weaponised drone, and the star of the exhibition, is the Warrior, a souped-up Predator that carries four laser-guided Hellfire missiles under its wings. The army calls it the Grey Eagle. “There are rules in army aviation that you have to have a

North American Indian chief or tribe name,” says Lt Col Kevin Messer.

Predator drones have been used extensively by the CIA to assassinate alleged al-Qaeda and Taliban militants in the tribal areas of northwest Pakistan. The army uses drones mostly in what it calls TIC (troops in combat) incidents. The CIA does not comment on its top-secret programme, though the New York Times reported this month that the intelligence agency believes it has killed more than 500 militants in the past two years “and a few dozen nearby civilians”. Other estimates of civilian victims range much higher.

Elsewhere in Washington – in think tanks, on university campuses and in the higher echelons of government – the reliance on unmanned aircraft to search out and kill perceived enemies has prompted heated debate. But here in the Pentagon the language is technical and acronym-packed, devoid of geopolitical or moral content.

Each army Predator costs $6 million “without payload”, Col Messer explains. I hear about its SAR (synthetic aperture radar), GMTI (ground moving target indicator) and EOIR (electrical optical infrared) ball. The drone’s ungainly “camel hump” hides a rotating satellite dish. Its mission is RSTA (reconnaissance, surveillance, target acquisition). “If it’s a target I want to prosecute, I can do it,” says Col Messer. “If it’s a target I want to kill, I can do it. It is the sexiest programme in the army.”

The technology is becoming more accessible. Forty-three nations are building military robots, as are some non-state actors, such as the Lebanese Hizbullah.

Critics of the US’s reliance on drones portray it as a cowardly weapon, since operators can kill without any risk to themselves. An executive order handed down by president Gerald Ford in 1976 banned US intelligence from carrying out assassinations. Before 9/11, US officials criticised Israel for assassinating Hamas leaders. That changed after the atrocities of 9/11, when George W Bush authorised the CIA to kill members of al-Qaeda and their allies anywhere in the world and Congress approved the measure.

On March 24th the state department’s legal advisor, Harold Koh, made the clearest statement yet of the Obama administration’s policy on drone strikes. Koh said the strikes were legal under the 2001 Congressional Authorisation for Use of Military Force, and under the principle of self-defence. He called them “targeted killings” – the Israeli term – not assassinations.

The Obama administration has more than doubled the number of drone strikes. Some influential policymakers, including Vice- President Joe Biden, advocate relying even more heavily on drones to fight al-Qaeda and the Taliban, to keep US soldiers out of battle.

The killing of Baitullah Mehsud, the leader of the Taliban in Pakistan, along with 11 family members and bodyguards by a Predator drone last August, was considered a triumph for US intelligence. But as Jane Mayer reported in the New Yorker , it took 16 missile strikes over more than a year for the CIA to kill Mehsud. Between 207 and 321 people were killed in those strikes, depending on which news reports one tallies.

Now the CIA is trying to kill Anwar al-Awlaki, the US-born cleric who is believed to have inspired the Fort Hood killings last November and the attempted car-bombing of Times Square this month. Awlaki lives in Yemen, where the drones are searching for him. If US authorities wanted to tap his telephone, they would need a court warrant. But the CIA can assassinate him with the approval of the National Security Council and no judicial review.

Peter Singer says there have been 134 unmanned airstrikes in Pakistan. “But we don’t call it a war. We perceive it differently.” There is also a danger, says Singer, that the military and CIA succumb to “the tempation of technology” and go after “low-hanging fruit”. He does not oppose drone strikes, but wants them to be handed over to the military – not the CIA. “I want someone in uniform to be in charge of that.”

In the US the drone strikes are presented as efficient, precise and costless. In the Middle East and Pakistan they are perceived as cruel and cowardly. Faisal Shahzad, the Pakistani-born US citizen who tried to detonate a home-made car bomb on Times Square, told a friend he was angered by the drone strikes in Pakistan. Critics question whether the political “blowback” from drone strikes outweighs the strategic advantage.