The Politics of an Assassination: Who Killed Gandhi and Why?

All Global Research articles can be read in 27 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

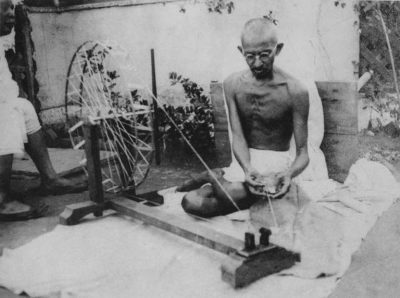

January 30th 2020. Commemoration of the assassination o Mahatama Gandhi. 73 years ago on January 30th, 1948.

This article was originally published on Hindustan Times in May 2017.

**

Historians and scholars have written extensively on “who killed Gandhi and why?” and the answer, obviously, doesn’t end with Godse. What Godse told the court in an attempt to explain why he chose to pump three bullets into Gandhi’s chest at point-blank range provides a glimpse into the politics of the assassination, writes Abhishek Saha.

On January 30, 1948, Mahatma Gandhi fell to his assassin Nathuram Vinayak Godse’s bullets during an evening prayer ceremony at Birla House in Delhi. Perched atop a gate of Birla House, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru announced to the world the “light has gone out of our lives”.

Eight men were convicted in the murder trial inside Red Fort by a special court, constituted by an order of the central government. Godse and co-conspirator Narayan Apte were hanged for the murder of the Father of the Nation on November 15, 1949.

Historians and scholars have written extensively on “who killed Gandhi and why?” and the answer, obviously, doesn’t end with Godse. What Godse told the court in an attempt to explain why he chose to pump three bullets into Gandhi’s chest at point-blank range provides a glimpse into the politics of the assassination.

Why Godse killed Gandhi

“I do say that my shots were fired at the person whose policy and action had brought rack and ruin and destruction to millions of Hindus,” Godse told the court.

He added:

“I bear no ill will towards anyone individually, but I do say that I had no respect for the present government owing to their policy, which was unfairly favourable towards the Muslims. But at the same time I could clearly see that the policy was entirely due to the presence of Gandhi.”

Godse had been an active member of the RSS and the Hindu Mahasabha and ran a nationalist newspaper called Hindu Rashtra. Political psychologist and social theorist Ashis Nandy wrote in his book “At the Edge of Psychology: Essays in Politics and Culture” that Godse did not find the RSS militant enough, and in the Hindu Mahasabha “he found a more legitimate expression of the Hindu search for political potency”.

Another section in Godse’s speech in court states: “To secure the freedom and to safeguard the just interests of some thirty crores (300 million) of Hindus would automatically constitute the freedom and well-being of all India, one fifth of the human race.”

In the speech, Godse also accused Gandhi of dividing the country into India and Pakistan.

Columnist Aakar Patel, writing in Outlook magazine earlier this year. “There is a problem with Godse’s argument and it is this. He thinks Gandhi was enthusiastic about dividing India when everything in history tells us the case was the opposite.”

Godse’s speech, Patel concluded, was illogical.

“Little of what Nathuram says makes sense by way of logic. It was his (Godse’s) hatred of the secular ideology of Gandhi, the true Hindu spirit that he is finally opposed to, having been brainwashed thoroughly by the RSS.”

Godse was not alone: The larger conspiracy

Extensive research by Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre for their book “Freedom at Midnight” detailed how exactly the conspiracy to kill Gandhi was hatched.

The book, published to critical acclaim in 1975, laid bare facts which prove that Gandhi’s assassination was the outcome of a larger conspiracy by Hindu fundamentalists to eliminate Gandhi from the political scene. Collins and Lapierre made full use of the access they had to critical police and intelligence records and even interviewed people who played key roles in the conspiracy, such as Nathuram’s brother Gopal Godse, Vishnu Karkare (who assisted Apte in hatching the plan) and Madanlal Pahwa, who unsuccessfully attempted to kill Gandhi ten days before he was shot dead.

In recent times, scholars and historians like AG Noorani have relentlessly written about how Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, the Hindutva ideologue and former president of the Hindu Mahasabha, was involved in the conspiracy but was acquitted only because independent witnesses could not corroborate approver Digamber Badge’s testimony against him in the court.

However, after Savarkar died, his bodyguard Apte Ramchandra Kasar and his secretary Gajanan Vishnu Damlewhen corroborated Badge’s testimony to the Justice JL Kapur Commission, which was formed to look into the Gandhi assassination conspiracy in 1966.

“Had the bodyguard and the secretary but testified in court, Savarkar would have been convicted,” Noorani noted in his essay “” in The Frontline magazine in 2012.

In the essay, Noorani cited letters written by then home minister Vallabhbhai Patel, who wrote to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in 1948 that it was a fanatical wing of the Hindu Mahasabha directly under Savarkar that “(hatched) the conspiracy and saw it through”.

Noorani also quoted correspondence between Patel and Bharatiya Jana Sangh founder Shyama Prasad Mookerjee, in which Patel writes, “…our reports do confirm that, as a result of the activities of these two bodies (RSS and the Hindu Mahasabha), particularly the former, an atmosphere was created in the country in which such a ghastly tragedy became possible. There is no doubt in my mind that the extreme section of the Hindu Mahasabha was involved in this conspiracy. The activities of the RSS constituted a clear threat to the existence of government and the state.”

In 2003, the NDA government installed a portrait of Savarkar in the parliament’s central hall alongside, ironically, those of Gandhi and Nehru.

The ideology that killed Gandhi: Where do we stand today?

As we celebrate the 69th anniversary of our freedom from colonial rule, it is perhaps worthwhile to ponder on what the politics of Gandhi’s assassination means in today’s socio-political context.

“There are two main understandings of Indian nationalism, one which considers Hinduism to be its central feature and the other which does not have such a neat definition but considers everyone who identifies with and adopts India to be Indian. Savarkar was the one who put the final seal to the ideology India as a Hindu nation. Gandhi, Nehru and others opposed this,” said Aniket Alam, executive editor of the Economic and Political Weekly (EPW).

Majoritarian Hindu fundamentalism and similar ideologies which were pivotal in the politics of Gandhi’s assassination are doing the rounds even today. But it would be incorrect to say that it was only the Hindu extremist political parties which were opposed to Gandhi’s principles.

As Alam pointed out, the Left parties and revolutionaries, BR Ambedkar and his followers, and Muhammad Ali Jinnah and his Muslim League were extremely critical of Gandhi’s politics.

“Thus when we say that Hindutvawadis attack Gandhi and despise Gandhi, we should not forget that he was intensely disliked by many others and some of these traditions continue in India today. They were not complicit in his murder but they would be equally happy to destroy his historical reputation and his political legacy,” said Alam.

Nonetheless, some historians say the Hindu extremist ideology which killed Gandhi is the same as the one which threatens India today.

“The communal forces and their divisive ideology which killed Gandhi were same as the ones we see today in the form of the Ghar Wapsi and Love Jihad campaigns,” said Mridula Mukherjee, professor of history at Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University.

“The main objective of communal forces is to increase antagonism between communities. It’s their aim to promote the idea that religious identities must be at loggerheads with each other. The vicious atmosphere that was created by them at the time of Gandhi’s assassination is the same as it is today.”

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Featured image is from Countercurrents